Meera Senthilingam

This week, Phil Robinson sends us to sleep…

Phil Robinson

‘No small art is it to sleep: it is necessary for that purpose to keep awake all day.’ Thus speaks the sage in Thus speaks Zarathustra, Friedrich Nietzsche’s work of philosophical fiction, pronouncing untroubled sleep God’s reward for a day lived virtuously. But Zarathustra, the vehicle for Nietzsche’s new, godless philosophy, is unconvinced – he dismisses the sage and his followers as unenlightened sleepwalkers, retorting ‘Blessed are the sleepy ones, for they will soon drop off.’

Now, whether you believe that deities dictate dozing, or that sleep is assuredly secular, adherents of both philosophies at least agree that sleep is not always easily achieved. Who has not lain awake feeling the dawn’s slow approach, exhausted but unable to slumber? Thankfully, merciful chemistry is agnostic and throughout history, the sleepless just and unjust alike have appealed to her for reprieve.

Alcohol and opiates have been used as sedatives since ancient times, and in Nietzsche’s age, toward the end of the 19th century, Justus von Liebig’s chloral hydrate was a widely used sleeping aid. Indeed, a lifelong insomniac himself, Nietzsche is said to have kept a well-stocked larder of soporifics, chloral hydrate in particular. But, even as Nietzsche was giving the sage and Zarathustra their lines, a new molecular Morpheus had been discovered and was itself lying dormant, waiting for its hypnotic potential to be awakened: barbituric acid.

This wholesale gentling of the nervous system not only brings sleep, but creates physical and mental states that gave barbiturates roles in physiology, psychotherapy, anaesthesia and, inevitably, recreation

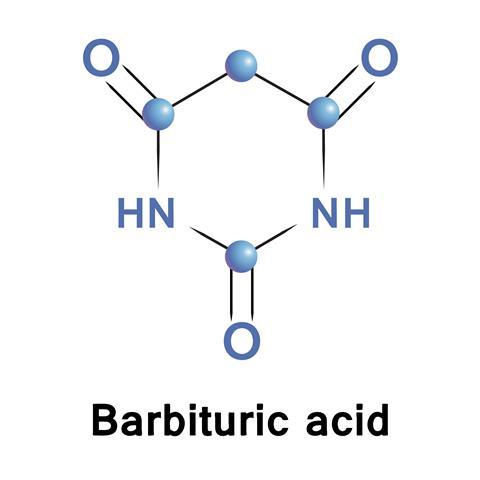

In 1864, the great German chemist Adolf von Baeyer was unpicking the chemistry of uric acid, isolated from urine by his friend Adolf Schlieper. Enjoying the first flush of independent research Baeyer derived a variety of compounds from uric acid, one of which he eventually found could be synthesised from malonic acid and urea – malonyl urea, a pyrimidine ring punctuated by three carbonyl groups. But Baeyer had already given his discovery a different name: ‘Barbara’.

The how and whom of Barbara’s appearance have become obscured, and even Baeyer himself seems to have practised an even-handed egalitarianism toward the various etymologies. In some, she is Baeyer’s sweetheart, or a Berlin bar woman, certain versions even crediting her with generously donating the raw material for her namesake. Another story has Baeyer’s discovery take place on December the 4th, the feast day of St Barbara, the patron saint of artillerymen. When Baeyer repairs to a local tavern to toast his achievement, he finds it replete with artillerymen, and with the waxing of the night, and the commingling of their celebrations, the compound is christened in her honour.

Whatever the truth, Baeyer had one more contribution to his compound’s story – placing it in the hands of his brilliant young student Emil Fischer.

Fischer cut his chemistry teeth investigating uric acid in Baeyer’s lab, and eventually surpassed his master by synthesising uric acid directly from urea. But it wasn’t until years later that Fischer and his physician friend Josef von Mering discovered barbituric acid’s peculiar abilities. For although it is biologically inert itself, Fischer and von Mering learned that with small modifications it became a potent sedative. They patented their invention and named it ‘Veronal’, either for being a ‘true’ hypnotic, or for Verona, the most peaceful place von Mering knew. The Bayer chemical company stepped in to produce and sell the new drug, capitalising on its founder’s now 40 year old discovery.

Veronal was marketed as a sleeping aid, and, unlike other products of the time, had few side effects, a pleasant taste and a therapeutic dose a safe distance from lethality – it was a huge success. Other modifications to barbituric acid were quickly tried and tested, giving birth to the family of barbiturates, which soon numbered hundreds. But bringing sleep was just the beginning of this family’s talents.

Biologically, barbiturates all act upon GABA receptors. When these receptors are activated by GABA molecules they inhibit the central nervous system by decreasing communication between neurons and so suppressing the brain’s activity. Barbiturates prolong the binding times of GABA molecules, enhancing the depressive effect. This wholesale gentling of the nervous system not only brings sleep, but creates physical and mental states that gave barbiturates roles in physiology, psychotherapy, anaesthesia and, inevitably, recreation.

In psychiatry, barbiturates were perhaps the first drug that truly supported treatment for mental illness, rather than simply sedation. Its work here began with Hermann Husen, a young German psychiatrist and insomniac who turned to Veronal to aid his own sleep. Impressed with the results, he tested the treatment on his patients in the sanatorium, bringing their anxious minds the relief of sleep. Within a few years, barbiturates would form the basis of sleep cures for mental illness.

Chemists have recently given barbituric acid a new lease of life

Just a few years later, another young German psychiatrist found himself denied sleep by his patients’ epileptic seizures. However, rather than self-medicating, he instead gave the barbiturate phenobarbital to his patients. With his patients soundly sedated, he got his sleep. But in the coming days he also observed that his patients’ seizures had abated. Epilepsy was added to the barbiturates’ growing list of treatments.

As with many other sedatives, barbiturates also impart loquacity. In the barbituric embrace, formerly silent, isolated patients become communicative and catatonic patients could be temporarily revived, permitting interaction, conversation and thus treatment. Narcoanalysis as it became known also found itself applied outside the clinic to induce involuntary verbosity, for which the barbiturate sodium thiopental became infamous as a ‘truth drug’.

Sodium thiopental was also one of the principal barbiturates that branched out into anaesthesia thanks to the speed with which it delivered a nervous-system knockout.

But as derivatives of barbituric acid proliferated, so did the reports of addiction and abuse. And although technically restricted by prescription, they were readily available. Barbiturate dependency and its high death rates, both accidental and intentional – and especially when combined with alcohol – brought barbiturates infamy. Through the mid-20th century, high profile names such as Marilyn Monroe and Jimi Hendrix were added to the growing list of casualties, for whom barbiturate addiction eventually brought irreversible repose.

Today, their use is heavily controlled and restricted to only a few specific areas of therapy and the much safer benzodiazepines are now the preferred treatment for anxiety and insomnia.

However, chemists have recently given barbituric acid a new lease of life. With hydrogens added to each of its nitrogens the molecule presents an alternating donor–acceptor arrangement of hydrogen bonding sites that can support extended networks of molecules, which have given it a central role in the emerging field of supramolecular chemistry. It may have been superceded in the clinic but there is no rest yet for barbituric acid.

Meera Senthilingam

Chemistry World’s Phil Robinson there, with the sedating and supramolecular chemistry of barbituric acid. Next week, a glitch.

Matt Gunther

On 30th January 1973, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Richard Helms, made a mistake.

Meera Senthilingam

Matt Gunther reveals this mistake and the chemical consequences resulting from it, in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet