Meera Senthilingam

This week, we go back to Roman times to mine for a very toxic compound. Here's Simon Cotton:

Simon Cotton

Readers of the historical parody '1066 and all that' will know that the ancient Romans were Top Nation, on account of their classical education. Some of their science was accurate too; they knew just how toxic mercury was. Mercury and some of its compounds have been known for over 2000 years; the Romans mined cinnabar, mercury sulfide, at Almaden in Spain. They sent criminals to work the mercury mines, and this was regarded as a death sentence.

The Romans used cinnabar as an orange-red pigment, but also roasted the cinnabar to get mercury metal. Whether you inhale cinnabar dust or mercury vapour, the result is the same: mercury poisoning. In the ancient world, mercury was used to make the amalgam with gold or silver that was used to silver mirrors and to gild glass or illuminated letters in manuscripts. After the amalgam was applied, the mercury was simply allowed to evaporate. Mercury compounds were used in medicine, to treat syphilis (ineffectively) and the metal was used in thermometers and barometers.

Many scientists fell victim to mercury poisoning, including Sir Isaac Newton, Michael Faraday and Blaise Pascal. Alchemists were keen to turn mercury into gold; King Charles II of England was a keen chemist, and his sudden death in 1685 is attributed to his inhaling mercury in the course of his experiments.

Mercury nitrate was used to preserve the felt used in hat-making, and also to soften the hairs. When the felt dried out, a toxic dust was formed. Workers absorbed mercury and developed symptoms including the hatter's shakes. The idea of the Mad Hatter in Alice in Wonderland was no exaggeration of Lewis Carroll's mind, though the character described exhibits none of the classic symptoms.

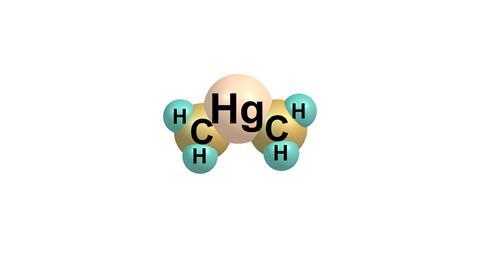

The most toxic mercury compounds are organometallics, containing mercury-carbon bonds. The first of these were made in 1852; Sir Edward Frankland found that if you left a mixture of methyl iodide with metallic mercury in sunlight, it formed crystals of methylmercury iodide. Many similar compounds followed. In the early 20th century, people started using them as fungicides on seed grains. They killed fungi, and people, too. Some people made bread direct from the grain, instead of planting it; mercury poisoning epidemics resulted. In Iraq in 1971-2, people ignored warnings on sacks of treated grain because they were in Spanish. Hundreds of people died. And when a Japanese chemical company discharged mercury wastes into the sea, anaerobic bacteria converted it into methylmercury, which was absorbed by plankton and passed up the food chain through fish to humans. The result was the poisoning of thousands of people at Minamata.

But dimethylmercury beats them all hands down for toxicity. It was first synthesised in 1858 by George Buckton, working at the Royal College of Chemistry (now Imperial College). Frankland's research group began making dimethylmercury in 1863. His colleague Carl Ulrich inhaled some after a spillage, and soon showed classic symptoms of mercury poisoning, sore gums and numbness of his hands, deafness and poor vision. He became restless and noisy before lapsing into a coma. He occasionally rose from the coma to emit howling noises, but died a fortnight after symptoms were first recognised. A young technician who assisted in the cleanup took longer to develop similar symptoms, but within months was demented, restless, violent and incontinent. He died of pneumonia a year later.

Even so, no one was prepared for the death of Karen Wetterhahn of Dartmouth College, US. She was a very experienced organometallic chemist who took all the precautions in measuring out a tiny amount of dimethylmercury in August 1996. She worked in a fume cupboard, wearing a lab coat, latex gloves and safety glasses. A colleague opened the chilled ampoule of dimethylmercury, and Wetterhahn rapidly pipetted it into the NMR tube, put the remainder into a storage vessel, cleaned up and disposed of the gloves.

Wetterhahn later remembered spilling a few drops of dimethylmercury onto the glove on that August day. Life carried on as normal; she went on with her research and teaching. In early January 1997, she started to notice worrying symptoms, slurring speech, problems with her balance. Five days later she was admitted to hospital and diagnosed with acute mercury poisoning. Her hearing and vision deteriorated. Chemotherapy to remove the mercury proved futile; on 6 February, just three weeks after the first signs of illness, Karen Wetterhahn went into a coma, dying on June 8th.

The scientists and doctors who treated Karen Wetterhahn concluded: - 'Dimethylmercury appears to be so dangerous that scientists should use less toxic mercury compounds wherever possible. Since dimethylmercury is a "supertoxic" chemical that can quickly permeate common latex gloves and form a toxic vapor after a spill, its synthesis, transport, and use by scientists should be kept to a minimum, and it should be handled only with extreme caution and with the use of rigorous protective measures.'

In 1865, the year Frankland's researchers died, George Buckton switched from chemistry research to entomology. He lived to the age of 87, dying in 1905.

Meera Senthilingam

So Buckton was luck to escape with no mercury poisoning. That was Simon Cotton with the toxic, deadly chemistry of dimethylmercury. Now, next week, a very versatile compound.

Jessica Gwynne

Rubber has been used in a huge variety of applications - tyres and inner tubes for transport; medical products such as gloves, catheters and contraceptives; and consumer products like clothing, erasers, balloons and sports goods. In the Far East, it is also used for seismic bearings, to prevent damage to buildings during earthquakes.

Meera Senthilingam

And to find out the chemistry which allows natural rubber to have such a wide variety of uses, join Jessica Gwynne in next week's Chemistry in its element. Until then, thank you for listening. I'm Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet