Meera Senthilingam

This week, a compound with a multitude of benefits. Hayley Simon explains more.

Hayley Simon

It’s the holy grail of pharmaceutical chemistry: a drug that can make you look and feel young forever. Unlike the fabled ‘fountain of youth’, human growth hormone, or HGH, cannot be drunk, commonly involves the use of needles and probably won’t do much to extend your lifespan. Though it has been touted by the Hollywood elite as a path to eternal youth, there is little evidence to suggest that using growth hormone can help healthy adults retain the vigour of their younger years. In fact, it is likely to cause more harm than good.

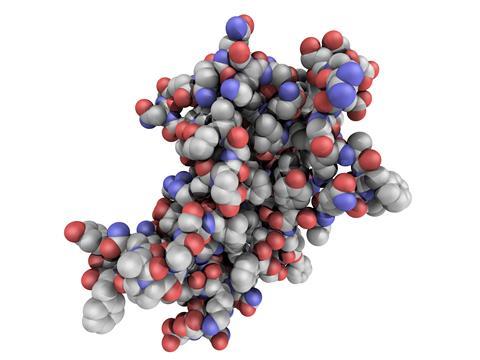

Human growth hormone is a peptide secreted by the pituitary gland. It consists of 191 amino acids and has a molecular weight of 22 kDa. In children with diseases such as Turner or Prader-Willi syndrome, which cause a deficiency in growth hormone, the recommended treatment is injection of HGH. Before the advancement of recombinant DNA technology, the only way to get hold of human growth hormone was to extract it directly from cadavers, a process with its own set of problems. Contamination of extracted samples led to the fatal Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD), sometimes referred to as ‘human mad cow disease’. This causes brain damage which worsens as time goes by. A safer treatment for growth hormone deficiency was not possible until the 1980s, when recombinant HGH was successfully engineered in the lab.

If you search online for ‘human growth hormone’, you’re bombarded by offers to purchase it as a health and fitness supplement. Soon after the hormone was first genetically engineered, its potential was recognised as a performance enhancing drug. Athletes hoping to increase their muscle mass and power inject HGH and take advantage of its anabolic properties. Often, though, the compound is used in combination with other steroids, which makes it difficult to determine whether improvements reported by users are due to HGH or other ingredients that are present. Dosage is often tailored to an athlete’s individual training plan and the desired effect can vary depending on the sport they are involved in.

Human growth hormone is banned by WADA, the World Anti-Doping Agency, in and out of all sporting competitions and appears on their list of prohibited substances. It has been on the international Olympic committee’s list of forbidden compounds since 1989, but it is only recently that a reliable test has been developed for its detection.

Before the introduction of the immunoassay-based test, doping with growth hormone was thought to be impossible to detect

Based on immunoassays, the new blood test was first introduced during the 2004 summer Olympic games in Athens, Greece, and works by detecting a change in ratio of the different types of growth hormone found in the blood. Under normal biological conditions, human growth hormone exists as several molecular forms. A syringe of recombinant hormone contains just one monomeric form: the 22 kDa peptide. When an athlete injects the drug, the natural ratio of hormone types in the blood is altered, and it’s this change that is detected by the test. Detection is achieved in two stages. First, the amount of the recombinant, 22 kDa hormone is determined and then the number of all other forms present is measured. The results are reported as a ratio of these two values and a cut-off point is used to distinguish between a positive and negative test.

Before the introduction of the immunoassay-based test, doping with growth hormone was thought to be impossible to detect, owing to the molecule’s short half-life in blood and low concentration in urine. Even with this test the window of opportunity to catch cheaters is just 24 to 36 hours after injection. The exact timeframe depends on the dose of hormone administered.

Though the test was first introduced in 2004, it was not until 2010 that it caught its first victim – rugby player Terry Newton. A year later in the US, the NFL – the National Football League – announced plans to bring HGH testing into the sport. After three years of hard negotiations, the NFL signed a new drug policy in September 2014.

Like any controversial issue, testing for banned substances sparks strong reactions in sports fans. Over the years, many famous athletes have tested positive for performance enhancing drugs and destroyed the trust of their supporters. With new, more widespread testing methods available, it is only a matter of time until more athletes abusing human growth hormone are caught in the act.

Meera Senthilingam

Chemistry World’s Hayley Simon there, with the controversial chemistry of human growth hormone. Next week, things get heated and smelly.

Brian Clegg

When heated, selenium dioxide sublimes at around 350°C to produce a greenish yellow vapour with a unique odour that is generally described as vile and smelling of rotting horseradish.

Meera Senthilingam

Brian Clegg explains the utility of such an odourous compound in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet