Ben Valsler

Look at your legs. If you’re wearing blue jeans – and it wouldn’t be surprising, every year we spend billions on them worldwide – then you’re part of a pigmented past going back thousands of years. Though, as Mike Freemantle discovers, sometimes you didn’t need the trousers at all…

Michael Freemantle

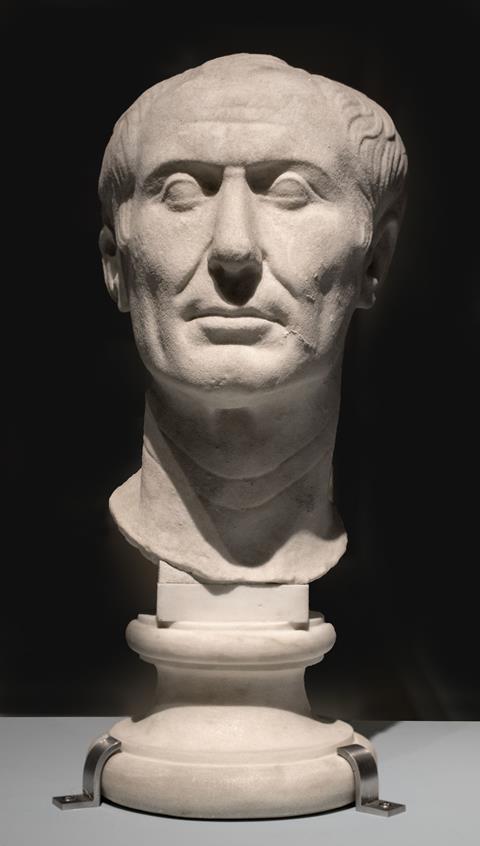

‘All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which occasions a bluish colour, and thereby have a more terrible appearance in fight.’

So wrote Roman military general Julius Caesar after his invasions of Britain in 55 and 54 BC. The quote is taken from a translation, published in 1869, of Caesar’s book Commentaries on the Gallic War.

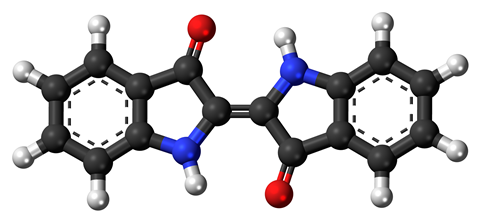

Woad is the common name of the plant Isatis tinctoria and also the name of the blue dye derived from isatin – a chemical precursor that occurs naturally in its leaves. The dye is indigo – a tetracyclic organic compound with alternating double bonds that give rise to its blue colour. Indigo is practically insoluble in water and does not occur naturally in the plant.

Indigo precursors also occur in numerous other species of plants. One of the most important is Indigofera tinctoria, native to Asia and parts of Africa.

The cultivation of these indigo-producing plants throughout the world can be traced back several thousand years. The dye is therefore probably the world’s oldest colouring material. It has been used not only for body art, but also in artists’ paints, for printing and especially for colouring textiles.

Indigo production typically involves fermenting the plants in a vat with an alkali such as potash. The precursors hydrolyse yielding a colourless but soluble form of the dye known as leuco-indigo. Fabrics to be dyed can then be immersed in the solution. After removal and exposure to air, the leuco dye is oxidized to form indigo, the insoluble blue pigment that attaches to the fibres of the cloth.

The yields of indigo obtained from Indigofera tinctoria are superior to those produced in Britain and other European countries from woad. The quality is also better. At the end of the 16th century, European countries therefore began to import indigo from other parts of the world, most notably from India. The Indian indigo industry subsequently flourished, and in the 19th century it supplied virtually all of the indigo consumed in the world.

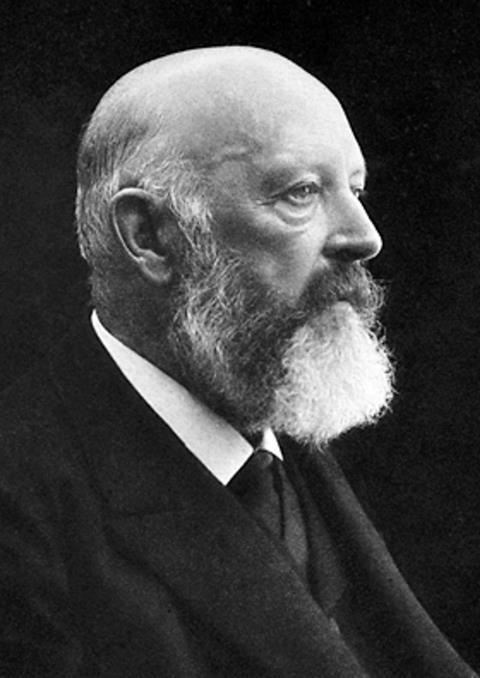

That changed dramatically with the advent of synthetic indigo. In 1870, the German chemist Adolf von Baeyer showed that the compound could be synthesized, albeit in low yield, from isatin. Then, in 1878, he managed to synthesize the precursor itself. He published the structure of indigo in 1883.

In the late 1890s, the German chemical firms BASF and Hoechst invested vast sums of money to develop processes for the large-scale production of synthetic indigo. BASF found an economic way of producing it from naphthalene and started selling it in 1897. Four years later, Hoechst began production using aniline as a starting material. Both naphthalene and aniline were inexpensive chemicals that could readily be extracted from coal tar.

Synthetic and natural indigo are identical chemical compounds. The natural dye produced in India, however, contained small amounts of other naturally-occurring colourants. Its quality was therefore inconsistent. The synthetic dye on the other hand was relatively pure and consistent in quality. Most importantly, the German chemical industry could produce the dye at a fraction of the cost of the natural material. As a result, the global demand for synthetic indigo rocketed at the start of the 20th century, while that for the natural dye plummeted.

The natural indigo industry in India revived somewhat during the first world war. Imports of the synthetic dye into Britain from Germany inevitably stopped when war broke out. But Britain needed the dye to colour its naval uniforms. So once again it began importing it from India. However, production in the country never reached the levels of the 19th century.

Nowadays, tens of thousands of tons of synthetic indigo are produced annually, mostly for the manufacture of blue denim jeans. There are concerns, however, about the synthetic material and its production. Earlier this year, Archroma, a Swiss colour and specialty chemicals company, announced the arrival of a ‘new aniline-free indigo for denim.’ In a statement, it noted:

‘Currently, aniline impurities are an unavoidable element of producing indigo-dyed denim. Unlike other chemical impurities, aniline is locked into the indigo pigment during the dyeing process and therefore cannot be washed off the fabric. Scientific testing has shown that aniline impurities are toxic to humans …’

The mass-scale industrial synthesis and use of indigo produce large amounts of hazardous waste by-products, which need to be carefully treated and removed. The search is now on to find environmentally friendly and less hazardous methods of making and using synthetic indigo. In other words, the manufacture of the blue dye and blue jeans is becoming greener.

Ben Valsler

That was Mike Freemantle with the history of indigo. Next week, a new voice for the Chemistry in its element podcast – Florence Schechter – brings us another ancient plant-based compound, used to soothe the agony of gout.

Florence Schechter

Although the history of medicine has been mostly filled with frustratingly ineffective treatments like bloodletting, trepanation and tying frogs around your neck, an actual treatment for gout has been available for over 35 centuries: Colchicine.

Ben Valsler

Find out more in Florence’s first podcast next week. Until then, get in touch with your suggestions: tweet @chemistryworld or email chemistryworld@rsc.org. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

No comments yet