Meera Senthilingam

This week 'Oh, how to name an element?' Especially when several groups claim its discovery. And, once named, how to say it? nobelium? Nobeelium? To clarify, here's Brian Clegg.

Brian Clegg

You'd think it was pretty straightforward to decide what an element is called. But element 102 has had more than its fair share of misunderstandings and arguments. To begin with there's the matter of how to pronounce its current name – nobelium (because it comes from the same root as the Nobel Prize) or nobeelium modelled on the way we say helium. Even the Royal Society of Chemistry's representatives had a raging discussion on this when I asked them, before plumping for nobeelium. And that's just the pronunciation – the name itself took a fair amount of sorting out.

Element 102 is one of the more stable of the short-lived artificial transfermium elements with a half life of 58 minutes for nobelium 259. But how did it get that name? Element names follow four rough patterns. Some – gold, for instance – had their names before we even knew what an element was. Others, like einsteinium, were named after a famous scientist who had a significant role to play in our understanding of atoms, while a third group are named after the place where they were discovered - take californium, for example. Finally, there are the odds and sods. The elements that don't fit anywhere else.

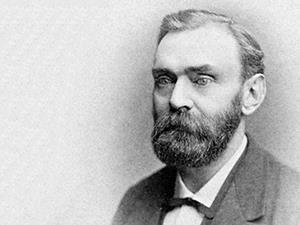

Nobelium can be seen as one of these. Some would argue that Alfred Nobel was a famous scientist. It's true that he was technically a chemist, but I challenge anyone to come up with a scientific discovery that Nobel is famous for. Born in Stockholm in 1833, Nobel was the son of an engineer. He worked in Paris with the inventor of nitroglycerine, a highly explosive but also very unstable substance, and dedicated a number of years to finding a way to make it usable, finally, in 1867, patenting the substance that would make his fortune, dynamite.

Nobel was responsible for the invention of a number of explosives and other chemical products, but was very much an industrial chemist, not the sort of person an element gets named after. The name, you might imagine, instead derives from the Nobel Prize, instituted in Nobel's will, where he declared (somewhat to the surprise of his family) that his fortune would be spent on a foundation to provide prizes in Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature and Peace. But thinking nobelium got its name from the Nobel Prize would be incorrect as well.

In all fairness, it should never have been given this name. The element was first produced in 1956, at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research at Dubna, then in the USSR. The discoverers named it joliotium after Irene Joliot-Curie, Pierre and Marie Curie's daughter. They seem at the time to have been totally ignored by the international community. It was only in 1997 that the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, the body that polices the naming of elements, admitted that the Russian lab did first create element 102. But by then it was too late.

Just two years after the creation of joliotium in Dubna, nobelium was made at the Heavy Ion Linear Accelerator at Berkeley, California, by bombarding curium with carbon ions. This experiment was undertaken by the team including Albert Ghiorso and Glenn T. Seaborg, who were responsible for isolating so many elements at Berkeley. Yet they didn't give the element its name. It had already been called nobelium for a year.

This is because a team at the Nobel Institute of Physics in Stockholm had announced the discovery of a new element the year before in 1957. Using a cyclotron to undertake a similar reaction, they thought they had produced an isotope of element 102 with a half-life of ten minutes. Not unnaturally they wanted to call the element nobelium. But their experiment could not be verified – such an isotope has never been shown to exist. So nobelium is a one-off, fitting somewhere between groups three and four. It's an element that is named after the place it was thought that it was first isolated, but really it wasn't.

Like most of the short-lived artificial elements, we don't know a huge amount about nobelium, though it has been produced in a range of ten different isotopes. It's expected from its position in the table that it would be a grey or silver metal, but there has not been enough made to check this. We do know a little about its chemistry. Unlike most of the actinides, the floating bar of elements that should be squeezed between actinium and lawrencium, which tend to have stable ions with a valency of 3 – that's to say, three electrons' worth of positive charge – nobelium's most stable ions are of valency 2.

Like all the artificial transfermium elements, nobelium is neither use nor ornament. Producing it was an achievement, but it has no practical value, nor is it ever likely to gain one. Although there was initially doubt over the naming of nobelium, perhaps it is only right that the name that finally stuck is associated with the Nobel Prize. It has been suggested that Alfred Nobel, influenced by his friend the peace campaigner Bertha von Suttner, set up the Nobel Prize as an apology for the harm caused by explosives. Out of the negative arose something very positive. In the same way, the Dubna laboratory might have missed out on the initial glory but now they are recognized as discoverers and linked forever to a name that has so much more impact than joliotium could ever have managed.

Meera Senthilingham

So in the end, there was victory all round. That was Brian Clegg with the non-explosive chemistry of nobelium. Now, next week, an element that seems to be misunderstood.

Quentin Cooper

Mistaken-identity history, its miscredited discoverer, its misleading and often mis-spelled name, all add to the aura of comedy and confusion around molybdenum...and yet it's an element that's right at the root of life – not just human life, but pretty much all life on the planet: yes you'll find tiny amounts of it in everything from the filaments of electric heaters to missiles to protective coatings in boilers, and its high performance at high temperatures mean it has a range of commercial applications.

Meera Senthilingham

What are those applications, you ask? Well, to find out join Quentin Cooper for next week's Chemistry in its element. Until then, I'm Meera Senthilingham and thank you for listening.

No comments yet