Ben Valsler

This week Georgia Mills examines the controversial killer, sodium fluoroacetate, aka 1080.

Georgia Mills

Sodium fluoroacetate is a synthetic salt, with a taste apparently similar to sodium chloride, but you definitely wouldn’t want this on your fish and chips.

Despite looking inoffensive – a pale white or colourless fluffy powder – and having no detectable odour, sodium fluoroacetate can be deadly to most animals, making it a popular poison.

Also known by the name 1080, it is used in many countries as a method for killing pests and invasive species.

It’s very similar to the naturally occurring compound potassium fluoroactetate. Several species of plant in a genus called Gastrolobium make this to try and dissuade herbivores from eating them, and the synthetic version was first made in the 1940s. It was created by treating sodium chloroacetate with potassium fluoride and it gets its brand name from the catalogue number of the poison: 1080. That’s a lot of poisons.

It is toxic to aerobic organisms, i.e. the chumps like you and me that need oxygen to survive. About 2–10 mg/kg will finish off your average human, while dogs, cats and pigs are more susceptible. It works by interrupting vital cell processes.

The molecule looks, to our cells, very similar to acetate, an important part of cell metabolism, and so they unwittingly convert this lookalike into something called fluorocitrate. This prevents an important enzyme – aconitate hydrase – from doing its thing, which has several knock-on effects. There’s a build-up of citrate – associated with impaired brain function; a reduction in calcium – which is required for heart and nerve function, and cells struggle to produce enough energy to function properly.

This can result in fitting, nausea, pain and eventually coma and death – there’s currently no effective antidote. It is by no means a quick, painless death for the animals who eat it.

Most of the planet’s annual output of 1080 is used by just one country: New Zealand. The poison is targeted at invasive mammals such as possums, rats and stoats to try and protect the native wildlife.

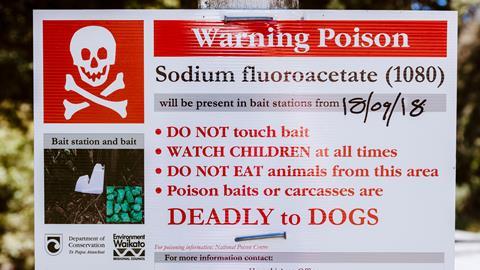

Despite numerous independent safety and efficacy studies, 1080 remains highly controversial. The poison is put into bait pellets, which are air dropped en masse throughout target environments. There are fears that such a toxic compound could easily enter the food chain or water supply.

1080 does sometimes kill the wrong animals – curious parrots called Kea like to investigate new and interesting items, and are an unfortunate casualty of the war on invasive species, alongside the occasional dog. Some animals, like fish and reptiles, are much more resistant to the poison due to differences in metabolic rates and their ability to convert fluoroacetate into the disruptive fluorocitrate.

But could it enter the water supply? Sodium fluoroacetate is water soluble, so can be dispersed through rain and groundwater. Fortunately, aquatic plants and microorganisms can break down 1080 into harmless byproducts. Similarly, any poison that leaches in the soil is likely to be broken down by bacteria and fungi.

As for worries about eating contaminated meat, the compound begins to decompose over 100 degrees celsius so cooking should handle most of it. Taking toxicity levels found in poisoned deer muscle, New Zealand environmental reports have claimed that an adult human would need to eat 100 kilograms of poisoned deer in one sitting for the toxin to be deadly – an ambitious meal for even the hungriest carnivore. While even low levels of poison may sound unpalatable, it’s worth mentioning that tiny amounts of fluoroacetate have been repeatedly detected in tea leaves, so long-term micro doses are unlikely to be dangerous, and given my 8-cup-a-day habit – if they are, I’ll let you know.

Anti 1080 sentiment remains high in some areas: it’s not risk-free and does not kill humanely. There’s also plenty of fake news to boot, even implicating 1080 in somehow causing roadkill. One famous incident in New Zealand involved a threat to poison infant formula with 1080 unless the government stopped using it. Luckily, two reliable test methods were quickly developed for the compound, and the blackmailer was put behind bars. Far from being an environmental activist, he benefitted financially from the sales of a rival brand of poison.

While the full extent of sodium fluoroacetate’s impact on the environment isn’t totally understood, safety measures and precautions are being used to try and mitigate potential damage, such as water monitoring, public notices and bait designed to look as unappealing as possible to the curious kea. For now at least, the people of New Zealand are taking the risk, because if they don’t do something, iconic birds like the kiwi will disappear forever.

Ben Valsler

That was Georgia Mills with the pest control salt, 1080. Next week, scents and sensibility, with Louise Crane.

Louise Crane

Its name comes from the Greek, hedone, which roughly translates as hedonism or pleasure and it is the only perfume compound that has been shown to stimulate a sexual response in humans.

Ben Valsler

Join Louise next week. Until then, if you can think of any compounds you would like to know more about, you can email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

Additional information

2 readers' comments