Meera Senthilingam

This week, Simon Cotton gets sporty.

Simon Cotton

Hosting major sporting events – especially ones that you are successful in – is good for morale, everyone gets swept up in them. The London Olympic Games of 2012 are an example of this, so was the 2005 Ashes series between the cricket teams of England and Australia.

For some nations, the desire for sporting success was so strong that they resorted to unfair means, in the form of drugs, to help them attain that end. The abuse of drugs really began after World War II. To begin with, it was amphetamines that were the drugs of concern, but testing for them was introduced in the Winter Olympics of 1968. Testing for steroids followed in 1976.

First isolated in the 1930s, testosterone, the natural male sex hormone, has anabolic effects, building tissue and muscle. Chemists soon found how to make ester derivatives that were easier to use, but all this research was for the benefit of helping sick and injured people get well quicker. After the second world war, Soviet weightlifters started to use testosterone to give them an edge, and they were quickly followed by American weightlifters and field athletes.

Although tests were developed to detect testosterone being used by sportsmen, its use continues today. But in the 1950s scientists were already looking to improve on testosterone. They made synthetic steroids that contained an alkyl group at carbon number 17, the same carbon that an OH group is bound to. This meant that they were tertiary alcohols, so it was harder for the liver to oxidise them, and also harder for enzymes to degrade them. This gave them stronger anabolic effects. The down side of this was that long-term use could result in liver damage.

The best known of these steroids are Dianabol and Turinabol. Turinabol in particular was widely administered to East German athletes and swimmers – without their knowledge - in the 1970s and 1980s, resulting in lots of medals but also lots of long term health problems. Then there was Stanozolol – a positive test for this resulted in Ben Johnson losing a gold medal at Seoul in 1988.

Once better testing procedures meant that drugs like Stanozolol were detectable, some people looked for steroids that could not be detected. Patrick Arnold was well placed to supply them; he was a chemistry graduate who was also a bodybuilder. He dug deep into the chemical literature, searching for steroids that had been tested but never brought to market, so-called ‘designer steroids’. He became involved with the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative (BALCO), who supplied these molecules to athletes. Norbolethone was one of these, it had never been marketed, so it was not a steroid that testers were expecting. When the testers did detect that, Arnold came up with an even smarter idea, a molecule that had never, ever, been made before; it was to become famous as THG.

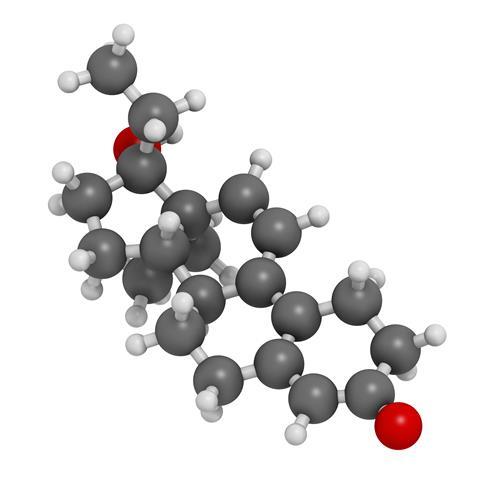

A steroid called gestrinone, on the other hand, was commercially available. It was originally devised, in 1974, as a contraceptive steroid. It has an alkynyl group – containing a carbon-carbon triple bond – attached at carbon 17. Arnold realised that converting the alkyne group to an alkyl group would make gestrinone into a carbon-17 alkylated steroid, likely to have real anabolic properties. It would just require the addition of four hydrogen atoms to turn the gestrinone molecule into tetrahydrogestrinone. To a skilled organic chemist like Arnold, this was easy, it just needed the reaction of hydrogen gas in the presence of a catalyst, and it was turned into THG. Once this had been done, THG was ready to be used. It is the presence of the alkyl group at carbon-17 that enables it to make stronger van der Waals’ contacts with the human androgenic receptor than do the other steroids, and that is why it has such strong androgenic properties, as well as its anabolic effects.

No one knows how many athletes took THG, or indeed how long its use would have gone on for had it not been for a snitch. Early in June 2003, an athletics coach contacted an official of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, saying that the head of BALCO had been supplying leading athletes with drugs; the coach promised to send the USADA a used syringe that had been thrown away at an athletics meeting.

The contents of the syringe were passed to Don Catlin, who at that time was the director of the Olympic Analytical Laboratory at UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) on June 13th 2003. He and his team got to work and within weeks they had identified the molecule, devised a test for it and for good measure had made it themselves. They detected it in samples taken from 4 athletes competing at the U.S. National Championships that month; then Dwain Chambers, the European 100m champion, gave a positive test on a sample given on August 1st. Most famously, Marion Jones, who won three gold medals and two bronze medals at the Sydney Olympics in 2000, admitted THG use and was subsequently stripped of these medals by the International Olympic Committee (IOC).

In October 2005, Victor Conte, the head of BALCO, was sentenced to four months in prison and another four on house-arrest, whilst in August 2006, Patrick Arnold was sentenced to three months in prison.

Chemistry made THG and chemistry unmasked it, in a kind of justice.

Meera Senthilingam

Birmingham university’s Simon Cotton there, with the performance enhancing chemistry of THG. Next week, can you tolerate this compound?

Lars Öhrström

The normal fate of this molecule in the body is hydrolysis. Water attacks and lactose is split into one molecule of glucose and one molecule of galactose. If this does not happen, you will get varying degrees of digestive symptoms such as flatulence, rumbling stomach or cramps.

Meera Senthilingam

And discover why lactose can cause such havoc in the body by joining Lars Öhrström in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet