Ben Valsler

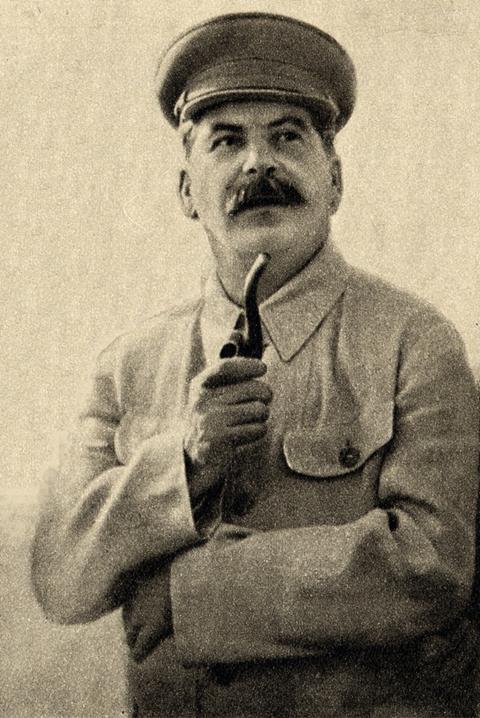

Katrina Krämer asks if an essential blood-thinning medicine ended Joseph Stalin’s 30-year rule over the Soviet Union…

Katrina Krämer

On the 1st of March 1953, Joseph Stalin, communist leader of the Soviet Union, didn’t get up as usual. The night before, he and his guests had been feasting and drinking at his estate just outside Moscow, so his guards weren’t concerned by Stalin having a lie-in. He had given strict orders not to be disturbed.

However, the dictator failed to emerge from his room all day. At 10pm, one of the guards finally plucked up the courage to enter Stalin’s room. He found his leader lying on the floor, semi-conscious. They called a doctor, but there was little to be done. Stalin remained unresponsive, his right arm and leg paralysed – signs that he had suffered a stroke. Four days later, the Communist leader died after suddenly starting to vomit blood. An autopsy later revealed cerebral haemorrhage as the cause of death.

However, not everyone believed Stalin had died of natural causes. Modern physicians re-examining the case came to think that he might been poisoned. The suspected culprit: the tasteless, odourless blood thinner warfarin – an essential drug that prevents deadly blood clots but can also cause bleeding when used carelessly.

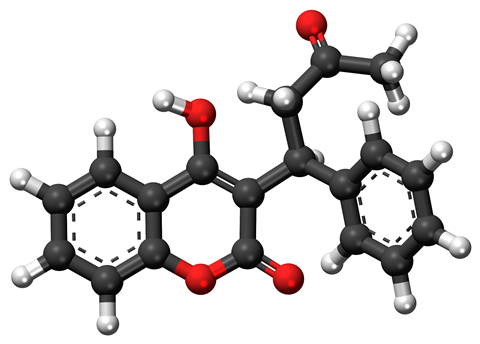

Before it was known as life-saving anticoagulant, warfarin was an exterminator’s favourite. Mixed with food bait, less than one milligram can kill a rat – though today many rodent populations have developed resistance. Warfarin was first made in 1948 by US scientist Karl Paul Link after he isolated a similar compound – dicoumarol – from spoilt sweet clover.

Almost three decades earlier, in 1920, a strange cattle disease had broken out in the northern US and Canada. Cows were bleeding to death after minor surgical procedures such as dehorning. A veterinarian finally figured out it was fungus-infected sweet clover hay that had killed the animals. However, it wasn’t until 1938 that Link’s team identified dicoumarol as the compound behind the deadly bleeding disease.

Link later created warfarin in an attempt to find a more powerful dicoumarol derivative. Named after Warf – the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation that Link was part of – and the ending ‘–arin’, in a nod to the plant molecule coumarin, warfarin became a popular rodenticide. Its therapeutic use, however, started off with an attempted suicide.

In 1951, a member of the US army tried to take his own life by ingesting warfarin rat poison. However, his full recovery after being treated with vitamin K, prompted researchers to investigate the blood thinner’s therapeutic use. Today, it is used to treat deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke and heart attack – in short, any condition that involves blood clotting in places where it shouldn’t.

Blood clotting is an essential and fascinating process. As soon as the body detects a damaged blood vessel, it activates specialised cells. They run through a complex enzymatic cascade and eventually produce fibrin, a protein that changes blood from a liquid to a gel. Warfarin inhibits certain enzymes within that cascade that depend on vitamin K, which is why the vitamin is a potent antidote. Since the drug inhibits coagulation, but doesn’t really change the blood’s viscosity, the common notation of warfarin as a ‘blood thinner’ is somewhat misleading. However, while life-saving in certain situations, warfarin can also cause uncontrolled bleeding. Each individual’s metabolism and genetic background dictates how they handle the drug, which can make finding the correct dosage quite tricky. Moreover, warfarin interacts strongly with many common drugs such as antibiotics and anti-inflammatories including aspirin and ibuprofen.

To make matters more complicated, many foods also interact with warfarin. Broccoli, spinach, cereal grains and vegetable oils are high in vitamin K and reduce the anti-coagulant’s effect, while alcohol, ginger, garlic and fish oils naturally increase blood-clotting time and therefore enhance warfarin’s tendency to induce bleeding.

Despite its fickleness when it comes to dosing, warfarin is on the World Health Organization's list of essential medicines for being one the most effective and safe anticoagulants. Although there are now a number of newer anticoagulants on the market, none of them has a well-established antidote like warfarin. For people with mechanical heart valves, taking warfarin remains crucial as it prevents blood from clotting on the foreign object.

Whether it was an overdose of warfarin that killed Stalin will likely remain a matter of speculation. The dictator’s successor wrote in his 1970 memoirs that a former security chief had confessed the murder to him. However, no concrete evidence was ever produced and the communist leader’s death remains shrouded in mystery.

Ben Valsler

Katrina Krämer with warfarin and the unanswered questions surrounding the death of Stalin. Next week, Brian Clegg on the chequered history of fertilizers.

Brian Clegg

It would be short sighted to not acknowledge the huge role that fertilisers have played in increasing and improving food production – and one of the key contributors is the simple inorganic compound potassium sulfate.

Ben Valsler

Find out more about potassium sulfate, also known as arcanum duplicatum, sal duplicatum, Glaser’s salt and more. Until then, let us know if there are any compounds you’d like us to cover – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. Thanks for joining me, I’m Ben Valsler.

1 Reader's comment