Companies are racing to develop alternatives to injectable diabetes and weight loss drugs

Injectable peptide drugs targeting the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor have had massive impact on approaches to treating diabetes and obesity, bringing huge revenue boosts to makers Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. Meanwhile, evidence is mounting of the wider therapeutic benefits of GLP-1 drugs, with clinical trials ongoing for metabolic liver disease, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, and neurological disorders, among others.

But the current peptide-based drugs are neither cheap to make nor easy to take. As the peptides cannot survive in the stomach, they have to be injected. The only approved oral GLP-1 formulation – Novo Nordisk’s Rybelsus (semaglutide) – combines the same peptide as Novo’s injectable Ozempic and Wegovy formulations with an absorption enhancer (sodium N-(8-[2-hydroxybenzoyl] amino) caprylate, or SNAC). This needs high peptide doses, and must be taken on an empty stomach with minimal liquid to ensure some of the drug gets through.

For the last decade, pharmaceutical firms have been racing to come up with an oral small molecule alternative, with mixed success. Eli Lilly looks to be the closest, with positive results from phase 3 clinical trials of its once-a-day pill orforglipron emerging in April, June and August. Those trials suggest that, while perhaps not quite as impressive as its injectable peptide cousins, the drug is still safe and effective at inducing significant weight loss.

GLP-1 drugs target the GLP-1 trans-membrane receptor, which is one of a large family of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) proteins that straddle cell membranes and transduce chemical signals from outside the cell to its interior. ‘Novo Nordisk, Pfizer and other big pharma companies have just taken [the hormone] GLP-1 itself, and spent 20 years stabilising the peptide, making it druggable, so it’s not broken down [in the body],’ explains John Unitt, vice president of immunology and inflammation drug discovery at Sygnature Discovery in Nottinghamshire, UK, and a GPCR drug discovery expert. Lilly’s tirzepatide (Mounjaro and Zepbound) is similarly a modified and stabilised form of the related glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) hormone. Add to this complexity the high cost of making and formulating such peptides, and a small molecule drug starts to look much more attractive.

Drugging this type of GPCR with small molecules has its challenges say Jeff Finer, chief executive of Septerna, a biotech based in south San Francisco, US. ‘A peptide hormone typically has extended binding interactions with the receptor … exactly mimicking these interactions with a small molecule is impossible. Layering on requirements for optimal pharmacological profiles and drug-like properties to support oral dosing adds another level of complexity.’

But acording to Terry Kenakin, a former GSK drug developer now at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in the US, ‘we are in what I call a renaissance in terms of finding compounds that modify the function of these [GPCR receptors]’. High throughput screening of millions of compounds across diverse chemical space is a starting point. Advances in cryo-electron microscopy imaging of receptor structures, and the ability to create dynamic models to understand how the receptors change shape, are now crucial parts of GPCR drug discovery that allow initial in silico screens. Although considerably smaller than the 3–4000Da peptide drugs, these small molecules are still around 700Da molecular weight – further adding to computational modelling complexity.

Lilly’s oral drug orforglipron was discovered by Japanese company Chugai Pharmaceuticals and licensed to Lilly in 2018. It is the first oral small molecule GLP-1 drug to successfully complete phase 3 trials, producing average weight losses of 8% after 40 weeks, and 12% at 72 weeks. The company anticipates applying for regulatory approval by the end of the year.

For an oral drug, the organ that receives the highest dose is the liver … 50% of all drugs fail on liver toxicity

Pfizer has not been so lucky. Despite reasonably successful progress in clinical trials of its most advanced oral candidate danuglipron, the company halted development in April, owing to a possible drug-induced liver injury in one participant of an earlier study. The problem resolved after discontinuation of the drug and overall the frequency of liver enzyme elevation for all 1400 trial participants was in line with the currently approved GLP-1 drugs. But Pfizer seems to have concluded that the toxicity question mark would damage its ability to compete in a relatively crowded space.

Kenakin says this is always a hazard: ‘If you have an oral drug, the organ that receives the highest dose is the liver … 50% of all drugs fail on liver toxicity,’ he says. Back at GSK he remembers waiting for phase 3 results, with champagne on ice, only to be disappointed by last minute indications of liver toxicity.

‘Individual safety findings for one molecule don’t necessarily predict class-wide effects,’ says Finer, ‘safety signals often relate to specific structural features or off-target activities rather than the primary mechanism of action.’ He thinks oral GLP-1 drugs have the potential for better dose titration, which might help control the current, mainly gastrointestinal, side-effects of the injectable peptides.

This was not Pfizer’s first or last oral GLP-1 disappointment. In 2023 the firm abandoned development of lotiglipron after trial participants showed elevated liver enzymes, and the same year discontinued a twice-daily danuglipron dosing regime after almost three quarters of treated patients experienced nausea, while almost a half developed vomiting and a quarter diarrhoea. And in August, Pfizer ended development of its third and final oral GLP-1 candidate, PF-06954522, after a review of its phase 1 clinical performance and the overall GLP-1 landscape.

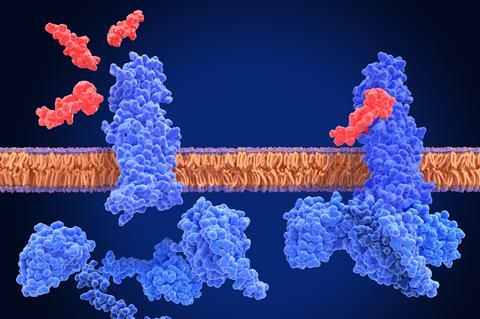

In May, Novo Nordisk agreed a partnership deal with Septerna to jointly discover and develop multiple oral small molecule obesity and cardiometabolic disease drugs. Novo will pay Septerna around $200 million in upfront and near-term performance milestone payments, with up to $2.2 billion promised based on the projects’ long-term performance. Septerna has developed a ‘native complex’ platform that can reconstitute the GLP-1 receptor within an artificial lipid bilayer, complexed with combinations of drug and internal cell signalling molecules, which replicates the dynamics of the signalling process at scale.

The platform has already allowed the company to identify a molecule that targets a novel binding site, distinct from that occupied by the natural GLP-1 hormone and current peptide drugs. Binding to this allosteric site can still influence the sensitivity and activity of the receptor, but could lead to drugs with fewer off-target side-effects, since GLP-1 is involved in many different metabolic signalling pathways. ‘Allosterics are great because they are usually very selective,’ says Unitt, ‘you’ll probably have a very good, clean drug.’

In 2024 Roche acquired Carmot Therapeutics, whose once-daily oral small molecule GLP-1 drug – CT-996 – was designed to have better signalling bias, meaning it preferentially triggers cellular pathways that lead to insulin regulation. Side effects with current GLP-1 drugs are attributed to the triggering of alternative pathways. The molecule is currently in phase 1 trials.

Another direction has been to target multiple receptors involved in stimulating insulin production. A recent head-to-head trial of the peptide drugs found that Lilly’s tirzepatide, which targets both GLP-1 and GIP receptors, produced greater average weight reductions than Novo’s semaglutide which targets only GLP-1.

Designing small molecules able to target multiple receptors might sound difficult, but Septerna says the allosteric binding site it has discovered is even better conserved across all incretin receptors than the site targeted by peptides and other small molecule drugs. The company’s collaboration with Novo will focus on single- and multiple-receptor-targeting drugs, exploring all possible binding sites.

Once an oral small-molecule GLP-1 is approved, there may be an expectation that it will take over from the current peptides. But while small molecules are likely to be cheaper to produce, Finer says it’s too early to project by how much. Kenakin suggests many patients have become comfortable with the current injectables, and may even prefer them ‘it’s a little pen and a tiny pin prick each week’ rather than daily tablets. But ultimately, says Unitt, it will depend how they perform in the clinic. They will need to match or improve on current performance and have fewer, or less serious side effects. ‘We’ll just have to wait and see,’ says Kenakin.

No comments yet