Governments around the world are starting to consider alternative funding models and incentives for antibiotics. Katrina Megget asks if it is enough

Big pharma has been talking about it for years. The only way the world could hope to tackle the impending disaster of antimicrobial resistance – which estimates suggest could result in 10 million deaths a year by 2050 – was to fix the broken antibiotic business model. In other words, change how pharmaceutical companies are rewarded for innovation. Do this, it was claimed, and big pharma, which has largely left the space in droves for pastures more prosperous, would come back into the fold. It’s been a slow grind to get governments to take action but now, as the reality of a post-antibiotic era looms, countries have started to commit themselves to exploring the options.

It couldn’t come at a better time – almost 5 million deaths were associated with drug-resistant bacterial infections in 2019, a study in The Lancet reported last year. The growing toll on society has resulted in a growing recognition by governments that this battle can’t be ignored, says Rohit Malpani, policy advisor at the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), which was launched as a not-for-profit partnership in 2016 to accelerate the development and access to antibiotics. ‘These current and future consequences have led governments to re-examine how best to develop and ensure sustainable access to new antibiotics… We believe there is real momentum to explore new business models, including those that employ not-for-profit approaches.’

The shift in direction comes after the realisation that the numerous push incentives – such as the 10 by 20 initiative, GARDP, CARB-X and the Repair Impact Fund – that have been introduced over the years to encourage research in a bid to address the dwindling antibiotic pipeline have, by themselves, been insufficient to address the crisis. New drugs have been developed – Malpani notes GARDP’s goal to deliver five new antibiotic treatments by 2025 is on track with one drug in their current portfolio, Shionogi’s Fetroja (cefiderocol), already approved – but the World Health Organisation (WHO) says this isn’t enough.

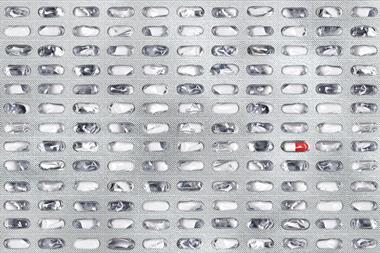

‘Push incentives have contributed to mitigating some of the challenges associated with antibacterial development but, in isolation and at the current scale, are insufficient to meet R&D objectives and bring sufficient products to market,’ a spokesperson from the WHO told Chemistry World. ‘Only 77 new antibacterial treatments are in clinical development and most are derivatives of existing antibiotic classes with well established mechanisms of drug resistance… We are facing an enormous issue.’

Market failure

The answer, the WHO says, is to strengthen the R&D ecosystem with sustainable and predictable financing but also to focus on rewarding R&D and for bringing products to market. ‘Pull incentives or other financing mechanisms are also needed to support the development of a sustainable pipeline of novel antibacterials and reinvigorate innovation across the life sciences ecosystem.’

It’s a similar theme in a 2022 report by Boston Consulting Group. While there has been limited success with the various push initiatives in lowering barriers to entry and bringing new drugs to market, the consultants say these ‘have not changed the underlying economics and thus market attractiveness and sustainability… Policies must foster a viable and attractive innovation ecosystem by rewarding successful development.’

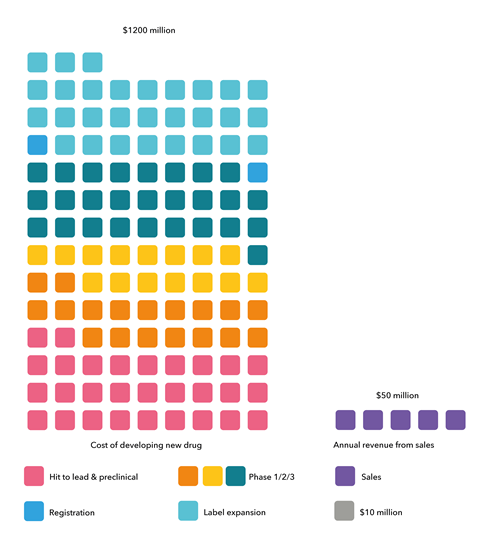

Providing push incentives without providing pull incentives is like building a bridge halfway across a raging river

It’s exactly what the pharmaceutical industry has been saying for years. It points to the grim reality of market failure – even with push incentives, three companies (Achaogen, Melinta, and Aradigm) with approved antibiotics on the market were forced to file for bankruptcy. It points to numbers that don’t add up, where it might cost $1.5 billion (£1.15 billion) to develop a new antibiotic yet median sales in the US of the most recently approved antibiotics reached just $16.2 million. It points to the fact that the existing economic model for antibiotics based on volume sales doesn’t work in a world where antibiotic use – especially new ones – needs to be conserved to contain resistance. And it points to the broader value antibiotics provide society, even if they aren’t used, which isn’t reflected in their price tags.

The bottom line is that the antibiotic business model is broken and pharma needs incentives to reward it for investing in the space. ‘Providing push incentives without providing pull incentives is like building a bridge halfway across a raging river,’ explains Henry Skinner, chief executive of the AMR Action Fund. ‘It will allow you to get moving but eventually you’re going to plunge off the end and drown.’

The AMR Action Fund was launched in July 2020 with support from more than 20 pharma companies in a bid to avoid that scenario and give an immediate lifeline to small firms. It was described as a stopgap initiative where companies would contribute $1 billion to invest in small biotechs, along with big pharma know-how, to help push promising drugs through phase 2 and 3 development with the goal of bringing two to four new antibiotics to market by 2030. It was essentially seen as ‘buying time’ to allow governments to get their houses in order and introduce sufficient pull incentives for the industry.

Last year, the first year the fund was operational, it committed approximately $100 million in capital, with a similar figure expected by the end of this year, Skinner says. ‘That’s a significant infusion of cash for a field of medicine that has been starved of private investment for the last two decades.’

If policymakers don’t do their part, the pipeline will continue to dry up

The fund has five portfolio companies collectively targeting six different priority drug-resistant pathogens, including all three drug-resistant bacterial pathogens deemed by the WHO as of ‘critical’ concern. Four out of those five had previously received push funding from CARB-X. ‘We have focused our investments where the clinical need is greatest, and we will continue to identify opportunities that will have the greatest patient benefit,’ Skinner says, noting that the fund is on track to hit its goal of two to four new therapies on the market by 2030.

But he acknowledges it’s not enough to address the severity of the AMR threat. ‘Let me be very clear: the fund was not set up to remedy all that ails the antibiotic market and we do not have sufficient resources to support every deserving antibiotic company.’ It was set up as a temporary lifeline; the onus is on governments to fix the broken business model, he says. ‘If policymakers don’t do their part, the pipeline will continue to dry up, small biotechs that are doing great science will continue to go bankrupt, and millions of people will continue to die from drug-resistant infections.’

Policy and pilots

Policymakers are aware of the threat and the need to act. In both 2021 and 2022, G7 finance and health ministers made commitments to take steps to address antibiotic market failure and create economic conditions that preserve the effectiveness of existing antibiotics and bring novel medicines to market. They reiterated their commitments in March this year, including to ‘monitor, co-ordinate and enhance G7 efforts to incentivise AMR R&D’ and ‘exploring the possibility of international collaboration on pull incentives for antimicrobial R&D, as appropriate’.

The market challenges plaguing antibiotic development will not fix themselves

Yet as the WHO notes in its AMR progress report for the G7 ministers, these efforts ‘remain insufficient’ to address the pipeline crisis, despite ‘substantial progress’. It emphasises the point: ‘[Pharma] industry representatives have signalled investment in AMR R&D will continue to decrease without a viable market.’

Skinner agrees. Despite repeated expressions of support for market-based solutions, he says governments aren’t moving fast enough. ‘The market challenges plaguing antibiotic development will not fix themselves. Scientists, entrepreneurs, investors and big drugmakers will remain on the sidelines until they see that governments are serious about rewarding the successful development of new antibiotics.’

There are exceptions where rhetoric is translating into action, however, and Skinner points to the UK as a notable example. Here, the world’s first pilot economic model was announced in July 2019 and, last year, following the success of the pilot with Pfizer and Shionogi, the firms signed contracts in England for three years for their antibiotics Zavicefta (ceftazidime and avibactam) and Fetroja (cefiderocol), respectively.

Dubbed a subscription-style model, the UK scheme is what pharma has been asking for – an alternative health technology evaluation process and payment system that delinks profit from sales, where pharma still gets paid for drugs that are held in reserve. And the scheme works well, with clinical usage and stewardship broadly in line with expectations, says Nick Crabb, programme director for scientific affairs at the UK’s health technology assessment body Nice (The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence), which was involved with the evaluation of the pilot. ‘The main value to date is demonstrating that subscription models, where antimicrobials are paid for based on their value and delinked from the volumes used, are viable,’ he says. A public consultation will be launched in July 2023 to review the details and the intention is to roll the model out UK-wide.

Under the pilot scheme, the payment the firms received was £10 million per product per year for a three-year period, extendable to a maximum of 10 years. This contract value was intended to represent England’s ‘fair share’ of a global pull incentive based on the country’s percentage of global pharmaceutical sales and the estimated cost that $2 billion to $4 billion would be needed globally to support the pipeline. Keiko Tone, general manager of Shionogi UK, welcomes the new de-linked model, calling it a ‘very constructive policy development’ that demonstrates successful stewardship.

But Tone believes the payment is not enough. ‘Along with other stakeholders, we do not consider this to be an appropriate level for any future scheme. In our opinion, the value of the payment level should fully reflect the true value of the antibiotic.’ She points to the valuation by Nice that concluded the antibiotics in the pilot were more valuable than the £10 million offered.

In reality, breakeven is not likely to constitute a substantial incentive

Tone also believes £10 million does not reflect the UK’s fair share, citing estimates that put this at £10–20 million per product per year. ‘Shionogi, along with other companies, have provided this advice to NHS England proposing higher payment levels for the permanent model to fully meet the policy objective.’

However, estimating the value of antibiotics and a sufficient pull incentive is not easy, says Lotte Steuten, deputy chief executive at the Office of Health Economics, a UK consultancy. ‘Depending on which countries contribute, England’s fair share of a global incentive should be a minimum of £12.4 million per annum,’ she says, but notes that that figure only equates to a financial return to pharma of essentially $1 above breakeven. ‘In reality, breakeven is not likely to constitute a substantial incentive, particularly when medicines for other diseases can generate higher returns,’ Steuten says. ‘If the pull incentive offered is less than the minimum required, it is eroding its effectiveness.’

The UK model could at least be described as a positive start. Steuten says the success of the UK pilot means other countries are looking at and learning from it. ‘This is a critical element because a pull incentive will only achieve the desired effect if more countries follow suit and collectively raise the global incentive needed.’ According to a paper published in the journal Health Affairs in 2021, an effective 10-year incentive would require a global contribution of £3.3 billion just for one new antibiotic.

Tone says a global incentive is important if companies are to be encouraged to invest in antibiotic R&D. ‘We hope to see leadership from as many countries as possible to implement pull incentives urgently.’

Global action

The UK approach is not the only proposed solution in the pull incentive space. Sweden introduced a partially delinked reimbursement model earlier this year after a successful pilot with MSD, Shionogi, Pharmaprim and Unimedic Pharma. Here, the state guarantees a minimal annual revenue to the pharmaceutical company, based on an estimate of the amount of antibiotics needed in stockpile, in return for the firm ensuring access to certain antibiotics. Unlike the UK model, the Swedish approach only preserves access to existing antimicrobials and does not encourage investment or support R&D.

Europe, meanwhile, is looking at a model based on exclusivity vouchers. ‘The premise here is when a company brings an antibiotic to market, they get an extension period on the patent but that patent extension is tradable,’ says Till Boluarte, managing director and partner at Boston Consulting Group’s Copenhagen office. ‘So they could sell this to other big companies and get a one-off payment for the voucher.’ He believes this is a positive move.

Germany and France are also exploring pull incentives, with a focus on providing minimum price guarantees. Japan has committed ¥1.1 billion (£6 million) in the 2023 budget for a support programme to secure antibiotics that target drug-resistant bacteria, and Canada is due to finalise its AMR action plan this year and a framework for pull incentives.

This act really addresses the most threatening bacteria with access to antibiotics

It’s the US, however, where many eyes are currently turned. The Pasteur (Pioneering Antimicrobial Subscriptions to End Upsurging Resistance) Act had been politically dead but was revived in April with its reintroduction in Congress, much to the relief of many. Initially introduced in 2020, it aims to implement a delinked subscription model to boost antimicrobial development, as well as encourage appropriate use and safeguard domestic supply. The budget of the Act would be $6 billion over 10 years with guaranteed contracts with companies of up to $3 billion each in return for ‘unlimited access’ to an antibiotic.

Lawrence Kerr, deputy vice-president for global health and multilateral affairs at the US pharmaceutical trade body PhRMA is thrilled the Pasteur Act is back on the table. ‘This act really addresses the most threatening bacteria with access to antibiotics. It’s a common-sense approach and ensures the availability of new, novel drugs… [If the act passes] this will really renew the effort in the US and globally to address this public health threat.’

Indeed, Boluarte calls the Pasteur Act a gamechanger. ‘This is because it will be a significant incentive for pharma companies because of the large size of the US population and it will provide revenue potential.’

Push and pull

It’s for this reason, and the actions of other countries in exploring pull incentives, that Boluarte is cautiously optimistic. Each country alone is not enough to make a difference to AMR but a group effort can make antibiotic R&D attractive and sustainable, he says. ‘We don’t need the whole world to commit to pull incentives but we need leading countries such as the G7 plus Europe to lead the way to make an impact on development and commercialisation.’

He isn’t bothered that the pull incentives being explored or how they are remunerated aren’t harmonised. It makes more sense for incentives to fit with the local country and its health system, he says. What’s more important is global alignment around novel antibiotic requirements and priority pathogens, and he points to the WHO as providing guidance on this. Kerr believes countries are aligned around the threat of AMR and the need to address it. ‘The challenge then is having a co-ordinated or consolidated global approach for a large enough incentive… We can have different pull mechanisms simultaneously just like the variety of different push mechanisms we have.’

But will it be enough to move the needle on AMR? Will it be enough for pharma to jump back in? Kerr says pharma is already committed – the AMR Action Fund is evidence of that. But the reality is ‘not that much has changed’, he says. ‘It’s no less risky for companies. Antibiotics are still a marketplace failure.’

Boluarte, however, points to the other reality – that antibiotics are the backbone of healthcare systems. Without them, the cancer drugs and other treatments – with the substantial price tags that pharma relies on – will be ineffective. ‘If pharma can break even with some profit, I’m convinced big pharma will invest.’

But for the needle to really shift on AMR, it’s about making sure the pull incentives don’t incentivise suboptimal or ‘me-too’ antibiotics, Boluarte says. This has been a concern raised in the past and given the WHO’s conclusions on the current ‘insufficient’ clinical pipeline, the concern is valid. As Skinner notes, the onus needs to be on well-crafted pull incentives that place an emphasis on innovative and novel products that meet the eligibility criteria. ‘Subscription models need to be structured to reward meaningful new antimicrobials that provide substantial patient benefits. Not every antibiotic developed should be eligible for an award through a pull incentive.’

Yes, the needle is shifting but it’s shifting slowly

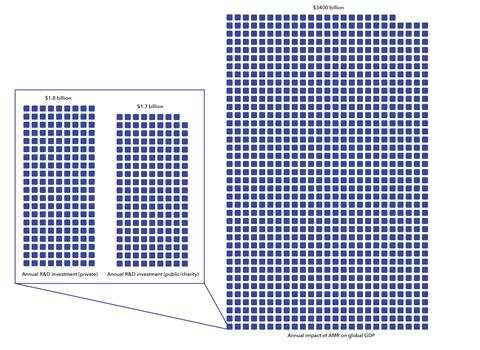

It’s for this reason that there will still be a place for push incentives to fund the more challenging and innovative early-stage research. In the WHO’s report for G7 finance and health ministers, the organisation concluded there was a significant funding gap in more ‘promising and innovative’ preclinical stages and noted that additional push funding is needed if the weak clinical pipeline is to be replenished. An AMR countermeasures study commissioned by the European Commission claims that additional global investment in push mechanisms should be between $250 million and $400 million per year.

This funding is critical, says Malpani. Not only will it assist early-stage discovery and development, it will also ‘ensure that development of a new antibiotic does not just focus on what may be the lowest hanging fruit or the most commercially profitable target but that it also addresses other needs, including treating certain resistant infections’, especially those affecting low and middle-income countries.

The landscape is fragile; the financial solutions and how to fund them to address AMR are not easy, especially in a cost-of-living crisis where money is already tight. But there is consensus that governments are moving in the right direction. ‘Yes, the needle is shifting but it’s shifting slowly,’ Kerr says. ‘The hope is this patchwork of different incentives will yield success. But my concern is bacteria and the evolution of resistance aren’t moving slowly.’ Given the long timeframe for antibiotic development, time is ticking for a sufficient global pull incentive. Until then, the needle will struggle to shift dramatically in the right direction against AMR.

Katrina Megget is a science writer based in Gravesend, UK

No comments yet