Arguments over precedence in Crispr development are set to resume

There is a new twist in the long-running dispute over who owns patent rights to the Nobel prize-winning Crispr–Cas9 gene editing technology.

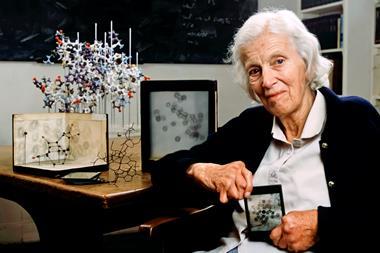

A team including Nobel laureates Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier lost its claim to key Crispr–Cas9 patents in February 2022, when a US Patent and Trademark Office Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) ruled in favour of Feng Zhang and the Broad Institute – a US-based collaboration between Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But now, Doudna and Charpentier have an opportunity to recoup the patent following a successful appeal of the PTAB’s ruling.

A 12 May opinion by a three-judge panel of the US Federal Circuit appeals court found that the PTAB had applied the wrong legal standard in reaching its 2022 decision regarding who first conceived the technology. The court has now ordered the PTAB to reconsider its ruling.

The dispute centres on which team first conceived the Crispr–Cas9 system for editing genes in eukaryotic cells and therefore whose patent on that technology has priority. Doudna and Charpentier’s team had argued that evidence from its lab proved it had conceived the idea as early as March 2012 and that a patent granted to Broad later that year was therefore an extension of their work. The PTAB’s 2022 ruling had stated the Doudna–Charpentier team’s evidence was insufficient proof of priority, but the appeal ruling has now found that the PTAB erred in applying the legal standard for conception, in part because it required the Doudna–Charpentier team to prove that it knew its invention would work.

‘Today’s decision creates an opportunity for the PTAB to reevaluate the evidence under the correct legal standard and confirm what the rest of the world has recognised: that the Doudna and Charpentier team were the first to develop this groundbreaking technology for the world to share,’ stated Jeff Lamken, one of the attorneys who represented the two scientists and their colleagues in the appeal proceedings.

Patent priority

Biochemist Doudna from the University of California Berkeley (UCB) and Charpentier, now at the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Germany, shared the 2020 Nobel prize in chemistry for their development of Crispr–Cas9, which acts like genetic scissors that can deactivate genes or introduce new ones in any kind of cell. That team published its use of Crispr–Cas9 to edit genes in Science in June 2012, after filing its first provisional patent application in May 2012. Those patents were not for its use in cells, however, and the first patent to cover its use specifically in eukaryotic cells, such as mammal and human cells, was granted to the Broad team in December 2012.

At the time these applications were filed, the US had a ‘first-to-invent’ patent system that granted patent rights to the individual who first conceived and reduced the invention to practice, irrespective of when they filed for a patent. In 2013, however, the US switched to a ‘first inventor-to-file’ system that grants the right to an invention’s patent to the first person to file a patent application.

Meanwhile, Broad says it is ‘confident the PTAB will reach the same conclusion and will again confirm Broad’s patents, because the underlying facts have not changed.’ The institute states that its patents are for genome editing and uses in eukaryotic cells – including cells from animals, humans, and plants – while UCB’s patents are not specific to uses in eukaryotic cells. ‘The UCB patents and the applications at issue here are all built on initial 2012 applications drawn from work in test tubes — not in eukaryotic cells — that do not support claims to genome editing or use in eukaryotic cells,’ Broad argues.

Back to court

Jacob Sherkow, who directs the Intellectual Property and Technology Law Program at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, calls the court’s new ruling ‘a victory’ for the University of California. ‘They do get a do-over at the PTAB, assuming that’s the next procedural step,’ he says. ‘It holds the possibility of, after all this time, the University of California claiming priority over single guide genome editing generally speaking, both in prokaryotes and eukaryotes, and that’s going to diminish – although I would say maybe not reduce to zero – the Broad Institute’s patents and what the Broad Institute is going to be able to command for a licence to them.’

The case is now likely to return to the PTAB as the Federal Circuit court has ordered. The PTAB will have to reconsider the evidence of the Crispr–Cas9 technology’s conception, including emails, lab notebooks and other records from early 2012, and determine whether they prove that the Doudna–Charpentier team originated the concept and that it could have been implemented using routine scientific methods.

However, Sherkow notes that Broad also has options to challenge the appeal itself. It could petition for the appeal to be heard again by all 12 judges of the Federal Circuit rather than the original panel of three – a somewhat ‘longshot’ option – and it could also petition the US Supreme Court to take up the case. Another option, which also seems unlikely, is that the parties could agree to settle.

No comments yet