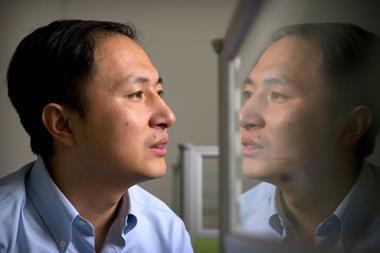

He Jiankui, a Chinese researcher now notorious for helping produce the first gene-edited babies says he is proud of his achievement. However, his actions may now unleash a global regulatory backlash against gene-editing.

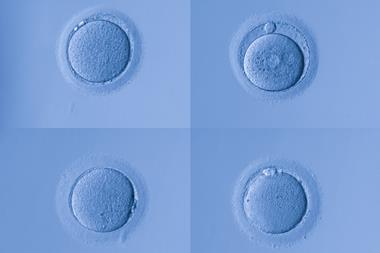

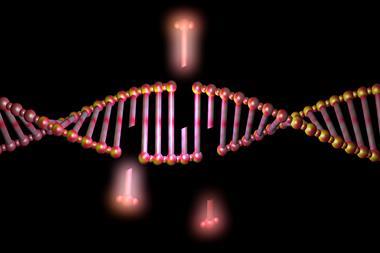

On Tuesday, He revealed how he edited human embryos at a presentation at the Second International Summit on Human Genome Editing in Hong Kong. The DNA of several embryos was altered using the Crispr–Cas9 gene-editing tool in an effort to make them resistant to HIV. These embryos were implanted and consequently twin girls were born to one couple. Geneticists are worried by this development as the edits made to the DNA of these babies will be passed onto any children they have.

His research drew withering fire from geneticists as unnecessary and ethically reprehensible. He’s university, Southern University of Science and Technology in Shenzhen, said it was unaware of the trial involving seven couples. The Chinese government has said it will halt the trial and begin an investigation.

‘The hope was that scientists would be able to self-regulate and everyone would be sensible and honour broad agreements,’ says Kiran Musunuru, a molecular biologist at the University of Pennsylvania, US. ‘We clearly failed. We are not able to self-regulate. I strongly suspect we will see more legislation and regulation at a national level, even in countries like China.’

My initial reaction, honestly, was horror

Kiran Musunuru, Penn State University

The first international summit on human gene-editing in December 2015 in Washington DC, produced guidelines for scientists. Some had argued for a moratorium on embryo editing, not guidelines.

A closing statement from the organisers of the second summit criticised He as irresponsible, citing poor study design, failure to meet ethical standard for protecting patients and a lack of transparency. Now, the controversy may have regulatory repercussions.

Flawed data

There was initial suspicion the gene-edited babies story was a hoax. This was partly because of the manner in which the announcement was made – not in a scientific journal but through the news agency the Associated Press. However, Musunuru was sure the story was true as soon as he received the flawed data from the Associated Press prior to the story breaking.

‘My initial reaction, honestly, was horror,’ says Musunuru. ‘What made it a hundred times worse was that it was immediately clear that both the embryos that became children had obvious flaws from the start. It was clear the editing had not worked as intended, as they were mosaics, with inconsistent editing across cells.’

The aim of the researchers was to knock out the gene for a receptor called CCR5. HIV uses this as a door into immune cells. A natural mutation in this gene confers almost complete immunity to HIV. CCR5’s role in the immune system is not fully understood, however. Worse, natural mutations in CCR5 are suspected to leave people more vulnerable to diseases like West Nile virus and influenza.

China concerns

Editing these embryos was no great scientific achievement either. ‘He simply did what others had done, but not been willing to cross the ethical line,’ Musunuru points out. Others are more scathing. ‘I’m not surprised that some fool went off and did this, the allure of attention and fame is just too strong for some,’ says John Doench, a geneticist at the Broad Institute in the US. ‘I am, however, saddened at what this will do for the reputation of a field, an institution and maybe even a country.’

Concerns about China had been whispered among the gene-editing community for years, though researchers were careful not to single out Chinese colleagues. ‘This work couldn’t really have been done in Europe or the US. The landscape in China is more permissive,’ says Musunuru.

Musunuru was approached last year by a Chinese scientist who had knocked out the PCSK9 gene involved in cholesterol metabolism. He was then asked about the next steps to prove it was safe for clinical use. ‘I was appalled,’ Musunuru says. ‘I don’t think it makes sense to knock out a cholesterol gene in an embryo. Heart disease is a chronic disease that affects older people.’

There are still serious questions about how consent was obtained from the couples involved in the trial. ‘The patients were given a consent form that falsely stated this was an Aids vaccine trial, and which conflated research with therapy by claiming they were ‘likely’ to benefit,’ comments Alta Charo, bioethicist at the University of Wisconsin, US. She was on the organising committee of the second summit and notes that He revealed ‘there is a second, early pregnancy’, as well as more edited embryos.

Off-target fears

One worry with editing human embryos is that Crispr–Cas9 can introduce mutations away from the target gene. The Chinese researchers found one off-target deletion, but decided that it would not be an issue. Others are not so sure. ‘Mutations can have unpredictable effects. There is a theoretical possibility that they could cause cancer or other diseases,’ says Musunuru.

Researchers worry that the scandal will set up obstacles for responsible gene-editing. Char fears that there will now be calls for an outright ban, but says ‘prohibition is neither necessary nor wise’. Strict regulations can manage the development and future uses of germline editing, she says.

The question remains whether gene-editing needs tougher policing or if this was one rogue operator. ‘The scientific community was already pretty unanimous in saying this shouldn’t be done, but this man circumvented the rules,’ says Doench. ‘It appears that this man acted fraudulently at several steps, including deceiving his institution and violating the ethics of informed consent. I’m not sure what more could have been done to prevent this.’

Musunuru believes He has been taken by surprise by the backlash. ‘He was in a rush to be the first to make gene-edited babies. He wanted the fame. I don’t think he realised it was going to be infamy.’ Musunuru says this debacle will be taught as a textbook example of how not to do medical research. ‘It is not a historic scientific achievement. It’s a historic ethical violation.’

Correction: The affiliation of Kiran Musunuru was updated on 3 December 2018

No comments yet