An 11-qubit quantum processor has been demonstrated by researchers in Australia using phosphorus atoms doped into isotopically-pure silicon-28.1 The researchers believe the system, which is highly robust to noise, could scale more easily than current quantum computers that use ion-trap qubits and the superconducting qubits that won the 2025 Nobel prize for physics.

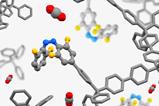

After the applied mathematician Peter Shor, then at Bell Labs in New Jersey, showed that a quantum algorithm could, in theory, factor numbers faster than a classical computer multiple proposals for practical implementation of quantum computers followed. One came from Bruce Kane, then a postdoc at the University of New South Wales, who proposed using traditional phosphorus-doped silicon.2 The material’s nuclear spins, which are very long lived, could function as qubits, and different nuclei could be coupled via a quantum mechanical interaction between the free electrons called the exchange interaction. This would allow for quantum gate operations, analogous to the logic gate operations in classical computing, but performing quantum logical operations. These could help to solve problems in high-temperature superconductivity, catalysis and even biochemistry that are classically intractable.

What is a qubit?

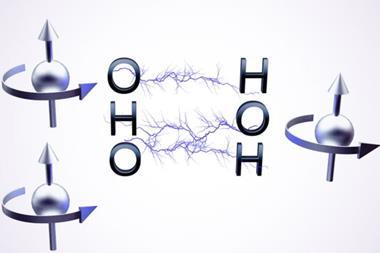

Conventional computers run on binary logic – encoding information as 1s and 0s in various ways such as the orientation of magnetic poles in a computer’s memory chip. These 1s and 0s, or bits, can then be harnessed to perform computational calculations through the use of logic gates. These gates allow a current to flow when the gate’s logic rule is met.

A quantum bit, or qubit, is the quantum computing equivalent of a classical computing bit. Qubits still encode information as 1s or 0s, but encode them in states of a quantum object such as the up or down spin of an atom. However, while a classical bit can only be in one of two states (1 or 0), a qubit can be in a superposition of states, which effectively allows the two states to be mixed in any proportion. This means quantum computers should, in theory, be able to handle information more efficiently.

This potential has theoretical chemists excited because using a quantum object to model other quantum objects (such as atoms and electrons) should be much more efficient. Quantum computing therefore enables us to simulate molecules without having to make a compromise between accuracy and computational cost that is typically required when trying to simulate molecules with a classical computer. (For a more complete discussion of quantum computing examining the limitations and necessary simplications required to explain the concept we have a feature on the topic.)

Kane’s specific protocol turned out to be technically impractical, and quantum computing turned to other platforms. All these, however, face severe technical hurdles such as the need for high vacuum or ultracold temperatures. However, the University of New South Wales’s Michelle Simmons explains that, if purified to reduce the silicon-29 content in natural silicon, silicon-28 could help to surmount many of these obstacles relatively simply. ‘It’s a group four element, all the electrons are used in bonds and it has very few isotopes with spin,’ she explains. ‘In that respect it’s a very good matrix that can hold the nuclear spins of the phosphorus atoms, but doesn’t interact with them. In our field they call it the semiconductor vacuum.’

Simmons and others have previously pioneered a modified version of Kane’s protocol. Last year, her group demonstrated the performance of a simple quantum algorithm using four qubits all coupled with the same electron.3

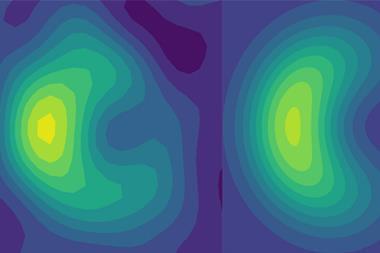

In the new work, the researchers produced an 11-qubit processor, with five qubits coupled to one electron and four to the other, and the two electrons linked together. At a temperature of 16mK, they could manipulate the state of each spin separately, perform gate operations and read them out using electromagnetic radiation and a magnetic field. In all cases, the gate fidelity was above 99%.

The researchers demonstrated the connectivity between the qubits by preparing highly non-local Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (or Schrödinger cat) states of up to eight atoms. The achievable entanglement of nuclei coupled to different electrons was similar to that of nuclei coupled to the same electron. The researchers were especially pleased to see that, as they added additional qubits, the quality did not degrade – which is promising for further scaling up. They are now looking at the possibility of quantum error correction, although Simmons says that the coherence times of nuclear spins are so long that the principal source of error is simply the residual silicon-29 in the material. Silicon-28 10 times purer than that used in the current experiment is now available, Simmons says, and the researchers hope to use it to create processors with more qubits and greater coherence times.

‘[The researchers] have made major advances,’ says theoretical physicist Barry Sanders at the University of Calgary in Canada. He cautions, however, that – though it was a preliminary step for established platforms such as trapped ions – the demonstration here stops short of actual computation. ‘Start with zeroes or some other agreed upon initial state, run your logic gates, describe it as a quantum circuit,’ he says. ‘I would then analyse it to describe width – how many qubits do I have – and depth – how many logical cycles do I go through to create [the final] state.’ He adds that ‘this meets my definition of doing exotic things that involve long-range entanglement; it fails my definition of doing computing’.

References

1 H Edlbauer et al, Nature, 2025, 648, 569 (DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09827-w)

2 B Kane,Nature, 1998, 393, 133 (DOI: 10.1038/30156)

3 I Thorvaldson et al, Nat. Nanotechnol., 2025, 20, 472 (DOI: 10.1038/s41565-024-01853-5)

No comments yet