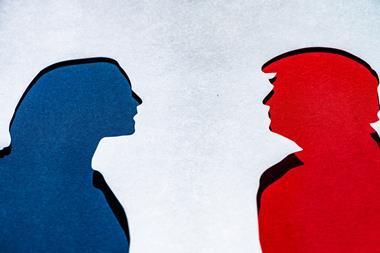

US researchers and science advocates were anxious when businessman and reality TV star Donald Trump was elected US president in November 2016. The unease many in the community felt back then has grown amid concerns that his administration has rolled back environmental standards and showed scant regard for science or truth. With the election looming on 3 November and a growing rift between the White House and the scientific community, Nobel laureates are circulating a letter endorsing Trump’s Democratic challenger Joe Biden.

Trump lives in a world of hype and public relations, spin and bluster, and you can’t do that with scientific data

Derek Lowe, drug discovery researcher

Most of the concerns expressed by the science community four years ago have come to pass, say dozens of representatives of academic research institutions and scientific organisations. These include slashing environmental regulations, immigration policies that harm the ability of US universities to attract foreign scientists, as well as repeated actions to undercut the role of science, data and evidence in policymaking.

Derek Lowe, a longtime drug discovery researcher and former registered Republican who had never voted for a Democrat for president until Hillary Clinton in 2016, calls Trump a ‘pre-scientific’ thinker. ‘He lives in a world of hype and public relations, spin and bluster, and you can’t do that with scientific data,’ says Lowe, who writes the widely read industry blog In the Pipeline.

Regulations reversed

The Trump administration has reversed or proposed reversing more than 80 environmental rules as of 22 July, according to analysis by Harvard University. These turnarounds include pulling the US out of the Paris climate change agreement in June 2017, and a sweeping rollback of a 50-year-old environmental bedrock law that requires ecological impact assessments of infrastructure projects and emissions standards for coal power plants.

This overhaul of the National Environmental Policy Act (Nepa), which requires federal agencies to assess the environmental impacts of projects like roads, oil and gas drilling, and new factories, is slated to go into effect on 14 September. Opponents of the rewritten rule, like the Union of Concerned Scientists, argue that it reduces the number of infrastructure projects that must undergo environmental review and silences community voices.

Beyond Nepa, Trump blocked the first-ever US standards to limit carbon pollution from coal power plants, established by former President Obama. Trump replaced that regulation in June 2019 with a new rule that doesn’t set limits on power plant carbon emissions, calling instead for efficiency improvements.

Dennis Paustenbach, a toxicologist and member of the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) science advisory board, doesn’t believe Trump explicitly wants to remove environmental protections. ‘Do I think [EPA’s administrator Andrew] Wheeler is intentionally rolling back the EPA in a major way, I don’t think so,’ Paustenbach tells Chemistry World, ‘but I do think he’s been told not to expand the regulatory arm of the agency at this time.’

Immigration mayhem

In one of his first acts as president, Trump issued an executive order imposing an immigration ban on seven countries in January 2017. Prominent researchers and academic groups spoke out, noting that US research institutes host many researchers from the targeted nations and warning that the edict was already harming US science.

The Trump administration tweaked the executive order twice, as it got tied up in courts over allegations of religious discrimination. Ultimately, in June 2018 the US Supreme Court upheld the third version of the directive, which affects travel from five majority-Muslim nations – Iran, Somalia, Yemen, Syria and Libya – as well as North Korea and some Venezuelan government officials. The policy remains in place today.

These anti-immigrant directives, one after another, are like waves striking on a shore; they relentlessly erode the competitiveness of many sectors

John Maraganore and Jeremy Levin

Now, academic and scientific groups are warning that other Trump administration immigration policies, many crafted during the Covid-19 pandemic, are disrupting the nation’s research. Of particular concern is guidance that forced international students whose universities switched to online classes due to the pandemic to leave the US or risk violating their visa status.

Universities and science groups immediately pushed back against that policy, with Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and many other universities launching lawsuits. The outcry worked. Just a week after announcing the directive, the administration rescinded it. However, new international students will still be prohibited from coming to the US next academic year if their universities run online only classes.

Only 74 out of nearly 3000 US universities surveyed will be fully in-person in the new academic year and 121 will be fully online, according to the Davidson College’s Crisis Initiative’s latest data.

Now, universities like Harvard and the University of Southern California are urging first-year international students to stay home since there is no guarantee about the availability of in-person classes.

‘This is a tremendously stupid and harmful idea, and even just proposing it … does a tremendous amount of lasting harm,’ Lowe tells Chemistry World.

Targeting China

Other recent visa policy tweaks by the Trump administration have also drawn the ire of the academic and research communities. In June, the president issued an executive order suspending new green cards and several non-immigrant visa categories, including those that universities often use for graduate and postdoc students, saying they disadvantage American workers.

Higher education organisations and science groups mobilised once more. ‘Preventing highly-skilled scientists and postdocs from entering the US will harm American science and threatens our scientific leadership,’ warned Sudip Parikh, chief executive of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

Just a few weeks earlier, Trump had issued a proclamation to block or cancel the visas of Chinese graduate and post-graduate students with links to universities affiliated with China’s army, saying that they may ‘operate as non-traditional collectors of intellectual property.’ The decree, which could cancel thousands of visas for Chinese graduate students and researchers currently in the US, went into effect in June 2020.

Industry has also expressed concerns. ‘These anti-immigrant directives, one after another, are like waves striking on a shore; they relentlessly erode the competitiveness of many sectors dependant on driving innovation, including America’s biotechnology sector,’ wrote John Maraganore, chief executive of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and immediate past chair of the Biotechnology Innovation Organization (BIO), and Jeremy Levin, BIO’s current chair and the chief executive of the biopharmaceutical company Ovid Therapeutics. Maraganore is a first generation American, and Levin is an immigrant from South Africa.

Minimising science

Trump has often been seen to be undercutting science and diminishing its role in policymaking. He has continued to publicly endorse the anti-malarial hydroxychloroquine as a Covid-19 treatment, despite the Food and Drug Administration revoking its emergency use authorisation in June.

Part of the problem is that Trump doesn’t always reveal sources or references for the data he cites

Donna Nelson, University of Oklahoma

‘This administration from the beginning has denigrated science and has implied that it isn’t important, that we don’t need to worry about it, that scientists aren’t credible,’ says Christine Todd Whitman, who led the EPA under former Republican President George W Bush and now runs an environment and energy consultancy.

The president took over a year and a half to appoint a science adviser, surpassing George W Bush’s previous record of five months. ‘The later that you put in place a science adviser, the less effective they are because they basically get cut out of the bureaucracy,’ says Lawrence Krauss, a physicist and science advocate formerly at the University of Arizona.

‘Part of the problem is that Trump doesn’t always reveal sources or references for the data he cites, which makes evaluation impossible,’ says Donna Nelson, a University of Oklahoma chemistry professor and former ACS president. ‘It is possible to find data that support almost any imaginable position, but not all data are valid.’

The Fauci factor

Trump has also faced opposition for apparently trying to undermine the US’s foremost infectious diseases expert, Anthony Fauci, who has served as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases since 1984. Fauci has advised six US presidents and sits on the White House’s coronavirus task force.

Fauci has had a difficult relationship with the president often refuting inaccurate statements and contradicting his message that the pandemic is under control. Polls have repeatedly shown that the US public trusts him over the president when it comes to information on Covid-19 by a wide margin.

In July, an unnamed administration official shared a memo with the media listing past comments by Fauci about Covid-19, many out of context, that purportedly turned out to be inaccurate. Following this a White House trade adviser wrote a blistering newspaper article claiming that Fauci ‘has been wrong about everything’. ‘Here is Anthony Fauci saying things that make Trump look and feel bad, so he must be destroyed,’ Lowe remarks.

Trump has also been accused of stacking science advisory committees at federal agencies, particularly the EPA, with industry representatives. One particularly controversial EPA policy, announced by former administrator Scott Pruitt back in 2017, banned scientists who are funded by the agency from serving on any of its science advisory boards. The prohibition was heavily criticised as squeezing out academics and weakening the scientific rigour of these panels. Ultimately, after a series of legal setbacks, the EPA announced in late June that it was abandoning the rule.

One of the science community’s greatest fears – that research agency budgets would be slashed under a Trump presidency – has not been realised though.

Congress to the rescue

‘President Trump’s budget requests for research funding have been poor overall,’ says Neal Lane, a physicist who was science advisor to former President Bill Clinton and also a director of the National Science Foundation (NSF). ‘The only reason that research funding has held its own and done pretty well is because of Congress.’

‘The story here regarding research funding in the era of Trump has been the administration doing its best to cut back dramatically on federal investment in scientific research and innovation, and Congress riding to the rescue,’ says Matt Hourihan, head of the AAAS’s R&D budget and policy programme.

The White House’s most recent budget request for fiscal year 2021 proposed cutting funding for the NSF and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) by 6% each, decrease the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Science by 17%, and slash the EPA’s science and technology account by 32%, according to AAAS analysis.

Congress has repeatedly rejected similar recommendations from the Trump administration. The budget for fiscal year 2021, which begins in October, remains under negotiation in Congress. ‘The president can influence the proceedings, but it is pretty clear that Congress still wields the power of the purse,’ Hourihan says.

‘Boringly safe’

Trump’s challenger in November, Joe Biden, is running as the pro-science candidate. In late June, amid concerns about Fauci’s treatment, he vowed to immediately reach out and solicit his help, if elected.

Biden’s ‘Innovate in America agenda’ proposes a $300 billion (£224 billion) investment over four years in R&D and ‘breakthrough technologies’ like electric vehicles, lightweight materials and artificial intelligence. It also calls for ‘major increases’ in direct federal R&D spending, including for the NIH, NSF and other grant programmes that fund university researchers.

This focus on research is not new for Biden. When addressing an annual AAAS conference in Texas back in February 2018, he said the US government ‘should be doubling and tripling down on investment in pure research across the board’.

In terms of science and research funding, Lowe calls Biden ‘boringly safe’ – meant as a compliment. ‘He is in favour of continued funding for these agencies, I don’t think he has any particularly radical ideas about changing everything up,’ Lowe says. ‘He’s not going to keep you up at night.’

Biden has already assembled some advisory policy committees in areas such as health and climate, naming senior academics and former science agency leaders to these panels.

‘I don’t expect presidential candidates to know about science – they are politicians – but I do expect them to listen to the people who know,’ Lowe says. ‘Trump doesn’t and Biden will.’

2 readers' comments