Biogen’s aducanumab is stumbling into obscurity. Where does that leave the amyloid hypothesis?

The story of Biogen’s Aduhelm (aducanumab), the most recent attempt at an anti-amyloid antibody therapy for Alzheimer’s disease, is both instructive and somewhat depressing. Perhaps that’s partly because I started my career working on Alzheimer’s. As I often say, if you had told me 30 years ago that in 2022 we would still be arguing about whether the beta-amyloid protein was the cause of Alzheimer’s (or at least a worthwhile target), I would have been horrified. But here we are, unsure whether amyloid gives you Alzheimer’s or if Alzheimer’s gives you amyloid.

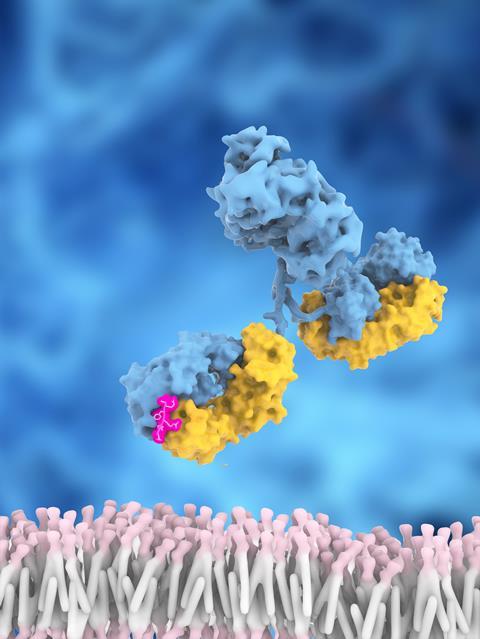

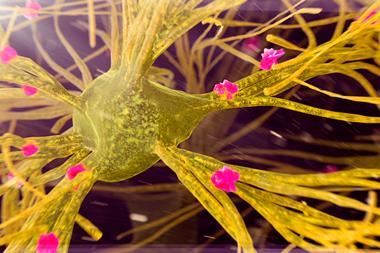

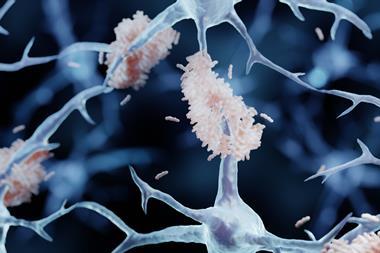

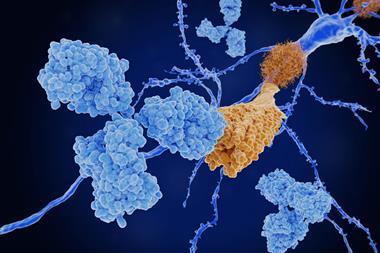

The reasons for these doubts are clear. Although deposits of amyloid protein are indeed evident in the brain tissue of Alzheimer’s patients (and seem to be surrounded by sickly neurons), every attempt to target these plaques has failed, through several different mechanisms. Biogen felt it had broken the pattern, but Aduhelm’s clinical data set off a terrible internal struggle at the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The clinical reviewers of the drug’s trials were favourably impressed by the outcome, while the agency’s own statisticians were scathing. They concluded that the data from the two trials were ruinously inconsistent, with no reason to accept one as the ‘right’ answer over the other, and that the only thing to do was run another trial entirely.

Here we are, still unsure whether amyloid gives you Alzheimer’s or if Alzheimer’s gives you amyloid

But the FDA approved Aduhelm anyway, and then the trouble really began. Several large insurance companies agreed with the FDA’s statistical review and would not pay for it. Then the agency that oversees the US government’s Medicare and Medicaid programmes confirmed that neither would pay for treatment outside of enrollment in a new clinical trial. That effectively ended Aduhelm’s chances of market success. Biogen had hoped to be the first company with a disease-altering Alzheimer’s therapy, but found the roof coming down on top of it instead. In April, Biogen withdrew its application for European approval.

As far as anyone can tell, this is a unique outcome. Many people (including myself) who thought that the drug should have gone through another trial before being approved in the first place, have cheered the market’s response. Others have warned that the entire accelerated-approval process that Aduhelm used has been damaged by these decisions, and that companies may well exit Alzheimer’s research rather than face the current uncertainties in drug approval.

If you’re working on an Alzheimer’s drug, you have already demonstrated a tolerance for risk far beyond normal levels

I doubt that. Alzheimer’s is the absolute definition of ‘unmet medical need’, and that need is growing all the time. Biogen is certainly not collecting the rewards of being first to market with an effective therapy, so that prize is still unclaimed. The uncertainties of Alzheimer’s drug development are not so much regulatory as they are scientific. We still are not sure what causes the disease in the first place. There is also no generally accepted animal model that recapitulates what happens in human patients – we are the only animal species that gets Alzheimer’s, as far as we can tell. The clinical trials are long, slow, and expensive, because you need a lot of people – treated for a long time – to have a chance of seeing a real therapeutic effect against this slow-moving disease.

This combination is deeply unappealing for drug discovery and development work, but it’s not the fault of the FDA or of Medicare. If you’re seriously working on an Alzheimer’s drug, you have already demonstrated a tolerance for risk far beyond normal levels, even the levels that are considered normal for the drug industry. As it is, 80–90% of our clinical trials fail, but the failure rate for Alzheimer’s is arguably 100% so far. There are a couple of drugs approved, but they just slow the development of symptoms, a bit, for some patients, for a little while. I cannot even estimate the amount of money and effort that has gone into trying to do better than that, in vain.

There are some believers left in the amyloid hypothesis, but many people in the field (and outside it) are at the end of their patience with beta-amyloid. I’d put myself in that group, too. I don’t know what should come next, but I think it’s time for the devils we don’t know so well. The one we know has been nothing but trouble.

1 Reader's comment