Biogen’s aducanumab offers the possibility to slow disease progress, but regulators will likely want more convincing evidence

In October 2019, Biogen unexpectedly revived an antibody treatment targeting Alzheimer’s, having abandoned clinical trials the preceding March. The company’s presentation at the Clinical Trials on Alzheimer’s Disease (CTAD) conference in early December therefore became a hotly anticipated opportunity for the community to get a better look at the data and understand Biogen’s decision.

The reception was mostly positive. Biogen will now file for US market approval for its amyloid-targeting antibody, aducanumab, but success is by no means assured.

Biogen stopped two Phase 3 trials (dubbed Emerge and Engage) on aducanumab after an interim analysis showed no measurable effect on cognitive performance over time. Then in October, the firm revised its position, claiming that the Emerge trial actually showed a significant effect, but the Engage trial did not, which sparked debate and some scepticism.

The situation is highly unusual. The interim analysis kicked off on 22 December 2018, ending in March. In that short window, a few hundred more patients who had received the highest dose of the antibody completed the trial. Data from these patients led to the October decision. ‘When they did the interim analysis, they didn’t have these data,’ says Paul Murphy, a neuroscientist at the University of Kentucky, US. ‘I am not aware of this happening for any other trial.’

Reduced cognitive decline seen in the first trial was attributed to that group starting earlier and taking the higher dose for longer – about a month. ‘It is a lot of handwaving and rationalising. That is not to say they are wrong, but it makes it dicey,’ says Murphy.

At the CTAD conference, the company showed that a subset analysis of patients receiving the highest dose for the longest time in the failed Engage trial, ten doses of 10mg/kg monthly, revealed slowing of decline. ‘If you look at people with the longer exposure to the highest dose, then the two trials had quite a symmetrical response,’ says Dennis Selkoe, a neurologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, US. For Jeffrey Cummings, a neuroscientist at the Cleveland Clinic in Las Vegas, US, it’s a plausible but not completely compelling explanation for the two different outcomes. ‘Additional data is likely going to be required,’ he says.

Trial experts at CTAD conceded that interim analyses are frequently done to save money on drugs that are obviously failing, but the Biogen analysis included just half the subjects, and the dose increased for some during the trial. ‘The consensus view was that in future, for chronic neurodegenerative disease, interim analysis should only stop trials causing harm, but not when the jury is still out,’ says Selkoe.

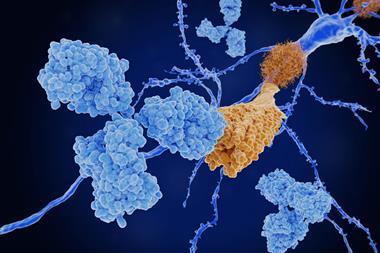

Aducanumab succeeded at clearing amyloid plaques in patients, a hallmark of Alzheimer’s. Many similarly promising antibodies, such as Eli Lilly’s solanezumab, had failed in late-stage trials. ‘Their decision [to stop the trials] was probably also influenced in a negative way by previous trials of other similar drugs that failed,’ says David Allsop, a neurodegenerative disease researcher at Lancaster University, UK.

I don’t think they have enough to get outright approval. What they have is equivocal

Still, aducanumab differs from other failed antibodies. Originally developed by Neurimmune in Switzerland, it was based on an antibody extracted from older individuals who did not develop Alzheimer’s, rather than being designed to target amyloid. Its preliminary results had impressed. ‘That was some of the best data that we had seen for an anti-amyloid therapy for clinical efficacy,’ says Murphy. Unlike other antibodies, it binds the aggregated form of beta-amyloid, not monomers.

Selkoe is a leading proponent of the amyloid cascade hypothesis, which views amyloid plaques as initiating the disease. But the strategy of targeting amyloid has been questioned, partly due to the number of failed antibodies. Selkoe counters that many trials were flawed, with a solanezumab trial recruiting 30% of patients who turned out not to have plaques. For him, a high dose is also crucial. ‘You must dose high enough for an [antibody] that is 150,000 Daltons and crosses the blood brain barrier very inefficiently, with levels 0.1 to 0.3% of blood levels reaching the nervous system.’ He suggests targeting amyloid should now be revived, noting that one of the first antibodies, bapineuzumab, was administered at around one-thirtieth the dose of aducanumab.

Light in the tunnel?

Aducanumab’s approval is certainly not secure. ‘I don’t think they have enough to get outright approval. What they have is equivocal,’ says Murphy. Many give it a 50:50 chance of conditional approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Murphy suggests that treating 10,000–15,000 more patients over five years might finally deliver an answer. ‘This is the only one that has shown promise. Maybe we should give it some conditional attempts to see if it works,’ he adds. Or the FDA could ask the company to rerun another, expensive Phase 3 trial.

Selkoe says the lesson is treat amyloid early, with high doses. ‘This is the first time in medical history that we have had what looks like a disease-modifying drug for Alzheimer’s,’ he says. On a daily living scale, patients in the highest dose groups had 40% less decline in Emerge and 38% in Engage. ‘This refers to everyday abilities, to make coffee, or do a transaction in a food store. Those are important,’ notes Selkoe. He supports conditional approval.

Others are similarly upbeat. ‘We are finally seeing some light at the end of the tunnel for people with Alzheimer’s disease,’ says Allsop. ‘Other ongoing trials with similar drugs will undoubtedly learn from this.’

Aducanumab is not curative. It cannot regenerate neurons damaged by inflammation, so is unlikely to help those with advanced disease. Rather, by clearing accumulated amyloid plaques, it may slow cognitive decline. Even so, many hope this will be the first Alzheimer’s modifying drug, which could be combined with subsequent drugs that target neuroinflammation or tau protein tangles.

The FDA will convene an expert review panel to scrutinise the aducanumab trial data, likely in the third quarter of 2020. ‘Clearly the company would prefer to get full regulatory approval,’ says Murphy, ‘but I don’t think the FDA would be doing its job if it approved based on what we know.’

References

J Sevigny et al, Nature, 2016, 537, 50 (DOI:10.1038/nature19323)

No comments yet