Ben Valsler

The benefits of some supplements seem to always be in dispute. One day it’s suggested that they are a panacea, and the next the evidence for any benefit is shown to be poor. Omega-3s, and the fish oil they’re usually delivered in, are certainly subject to the yo-yo-ing of public opinion. Here’s Hayley Bennett.

Hayley Bennett

Many of us have a bottle of cod liver oil capsules lurking at the back of our medicine cabinets, along with a vague sense we should be taking them for something. These fishy supplements are supposed to keep us stocked up on omega-3s. Higher strength capsules contain about the same amount as a generous portion of farmed salmon. So what is an omega-3 and what makes fish oil one of the most ubiquitous food supplements on the market?

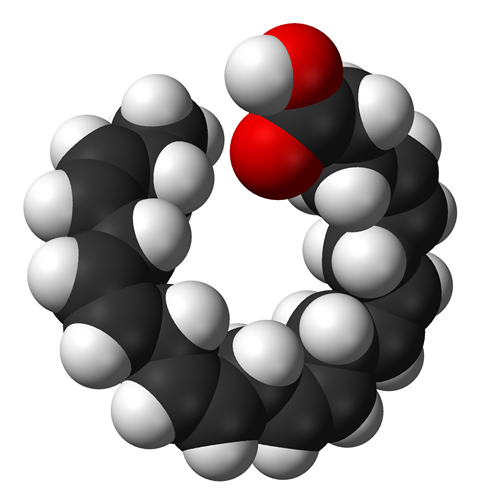

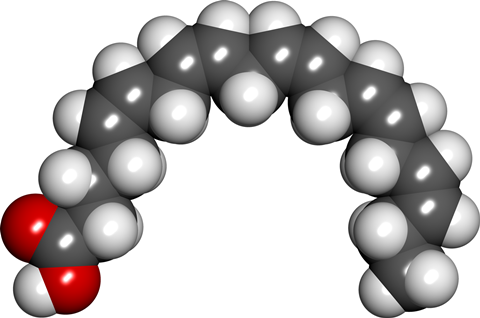

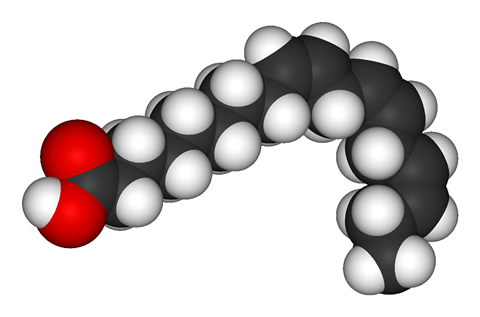

Omega-3s are a family of fatty acid molecules that are integral to every cell in our bodies. One of their most important jobs is to keep things loose and a bit kinky. In a structural sense, that is. They form the tails of the fats that make up the outer membrane of each cell – the bit that holds it all together. If they weren’t a little bit kinked, all of those chains would pack in alongside each other like sardines in a tin, leaving no space for anything to squeeze through.

But Omega-3s are unsaturated fats. Their kinkiness comes from the double bonds in their tails and is what keeps the packing loose enough for nutrients and signalling molecules to move in and out smoothly. With the right balance of saturated and unsaturated fats in our cell membranes, the work of the busy cell continues unhindered. If the balance gets upset, it can be a harbinger of disease.

What’s weird, though, is that despite their absolute necessity, we humans and many other animals can’t make these molecules ourselves. We don’t have the enzymes required to insert those kink-inducing double bonds or to make anything longer than an 18-carbon fatty acid chain. We have to get our omega-3s from somewhere else: our diet. That’s where fish oil supplements come in. Oily fish like salmon, mackerel, herring and anchovies are flush with omega-3 fatty acids and in particular, eicosapentaenoic acid, or EPA, and docosapentaenoic acid, or DHA. These two molecules are thought to be crucial for heart health and keeping our immune systems in check. DHA is also an important component in the membranes of our nerve cells and the light-absorbing cells in our eyes.

However, we’ve recently started to question the health benefits of the omega-3 supplements we’ve taken for granted for so long. In 2018, the Cochrane Library unveiled the biggest medical review to date on omega-3s for preventing heart disease. In the studies included in the review, taking EPA and DHA capsules made little difference to people’s risk of heart problems or dying from them. So is it really worth taking them?

Some have since argued that it’s the supplements that aren’t working and we should test a diet rich in oily fish, but doing that experiment is a challenge. To measure the benefit of any treatment properly, it’s best to compare it to a placebo and the people taking part in the experiment should be ‘blinded’ to which they’re getting. This is fine if your treatment comes in pill form, but it’s a bit more difficult when it’s a fillet of mackerel.

And what if you don’t eat fish? Luckily, our bodies can make EPA and DHA if they have another, shorter, fatty acid as a starting point. Alpha-linolenic acid, ALA, comes from plants. So for vegetarians, eating foods like walnuts and flax seeds can give them the basic framework to make all the essential omega-3s they need.

There’s also another option for those who seek to avoid fishy dinners and pills: algae oil. As I just mentioned, most animals can’t make omega-3s and, in fact, fish are no exception. They get them from their diet too – from microscopic algae in the oceans. In fact, until very recently, it was thought that this was where most of the omega-3s in the world were coming from, with fish simply transferring them up the food chain to us. As a result, the food supplement industry has been investing in algae farming as a source of fish-free omega-3s. Green microalgae can be grown in open ponds or in the controlled environment of a hi-tech microalgae aquarium, made up of hundreds of metres of glass tubes.

As it turns out, though, lots more animals than we thought can make omega-3s. In May 2018, researchers revealed that many invertebrates, including worms, corals and octopuses, have the genes to make their own omega-3 fatty acids. This really changes our view of the omega-3 landscape. Whether it will change where we get ours from remains to be seen.

Ben Valsler

Hayley Bennett with omega-3 fatty acids. Next week, Gege Li delivers a dose of medicine for sleeping sickness.

Gege Li

With the severity of the disease comes an equally severe treatment, which is where our deadly friend arsenic comes in – specifically, in the form of a derivative in a drug called melarsoprol.

Ben Valsler

Until then, get in touch with any suggestions for compounds to cover – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

No comments yet