In his final report on antimicrobial resistance (AMR), UK economist Jim O’Neill has set out 10 recommendations to tackle this economic and security threat, a scourge which he says deserves attention from heads of state. Last week he highlighted four: the need to encourage the supply of new drugs, to boost diagnostic technologies and to cut down on the unnecessary use of antibiotics in agriculture, as well as a public awareness campaign. But is the world ready to swallow his policy prescriptions?

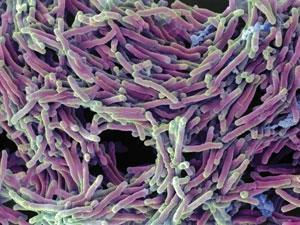

O’Neill’s report reveals the antibiotic resistance problem is getting worse, something backed by the latest news reports of the emergence of bacteria in the US resistant to the antibiotic of last resort. The report estimates one million people have died as a result of AMR since the review began in the summer of 2014, having previously forecast 300 million premature deaths by 2050. While resistance to antimicrobials expands, the pipeline of new drugs has slowed to a trickle.

The Pew Charitable Trusts recently described a 30-year void in the discovery of new types of antibiotics, with all those approved today derived from a limited number discovered by the mid-1980s. The scientific challenge has not really registered yet – US venture capitalists ploughed $38 billion (£26 billion) into pharma R&D between 2003 and 2013, but only $1.8 billion went into antimicrobials.

The report sets out how to refill the drug pipeline and head of AMR – at a cost of $40 billion over 10 years. It is confident the benefits will exceed costs and is sanguine money will be found. However, the final chapter on implementation is less surefooted. O’Neill’s tenth recommendation points to the battle ahead: ‘None of this will succeed without building a global coalition for action on AMR.’ Countries such as Brazil, India and China will need to participate for this to work.

Which way now?

Existing institutions might be best placed to manage supranational incentives, rather than a new body, the report notes. Governments could agree to pool funds into one entity and the G20 is proposed as a forum. John-Arne Røttingen, infectious disease and health policy expert at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, views the G7 as too narrow, while the UN is too complex to get an agreement. ‘The G20 can collectively decide on financing. That could include the market entry reward fund and innovation fund, but also financing for low income countries to tackle the more basic challenges,’ he adds. However, it needs to be channelled through a new institutional financing facility.

The Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria was set in motion after a G8 meeting in Japan, but the G20 has no form in health issues. ‘I don’t share their level of optimism on the G20,’ says Amanda Glassman, director of global health policy at the thinktank Center for Global Development. She believes the World Bank is better placed to step up in terms of global public health issues.

‘We tend to focus too much on developing new antibiotics instead of conserving our existing ones,’ says Devi Sridhar, global health expert at the University of Edinburgh, UK. ‘The best way to manage resistance is to ensure antibiotics are not overused.’ In developing countries, that means better public health infrastructure so that prevention curbs demand for pills. ‘Having better management for common ailments, better diagnostic tools such as for pneumonia and simpler treatments can help reduce the need for existing antibiotics,’ says Sridhar. This might not sound as exciting as new drugs, but can extend antibiotic lifetimes.

The UN and G20 must engage, but so to must the private sector, civil society and charities. ‘There is a real case for creating a new initiative that integrates non-state actors,’ notes Sridhar.

‘[O’Neill has] set up a great scheme on incentives for the development of new antibiotics,’ Glassman adds. ‘But I’d like to see more about what money is on the table for surveillance, on studying antibiotic usage and use of antibiotics in agriculture.’

Diagnosing the problem

O’Neill advocates for a global public awareness campaign at a cost of $40–$100 million. Awareness that antibiotics aren’t needed for a cold has risen in rich countries, but the risk of antibiotics in livestock is often overlooked, says Helen Boucher, infectious disease specialist at Tufts Medical Center, US. ‘Many don’t understand how important antibiotics are in supporting invasive therapies we take for granted. There is a need for awareness campaigns even in the developed world,’ she says. ‘The needs are even larger in the developing world, where antibiotics are often sold over the counter.’

[[It is in China’s power to lead the world in tackling the AMR problem ]]Estimates suggest that as much as 70% of antibiotics are prescribed inappropriately. O’Neill cites campaigns that cut antibiotic use 36% during last winter in Belgium. UK doctors have also recently been praised for cutting antibiotic prescriptions in England by 7% on last year.

An ideal solution is improved diagnostics, and rich countries can lead the way. ‘They should make it mandatory that by 2020 the prescription of antibiotics will need to be informed by data and testing technology,’ the report states. The aim is to establish markets and spur investment. An innovation fund would support early stage research, and a market stimulus would provide top-up payments when diagnostics are purchased in low and middle-income countries.

One obvious move is to trim antibiotic use in agriculture. The report cites previous research suggesting that the economic benefits of antibiotics in agriculture are relatively marginal. But in the US, over 70% by weight of medically important antibiotics for humans are sold for use in animals. It argues for further economic analysis to understand the impact of reducing unnecessary use, especially in low and middle-income settings.

The G20 is an ideal forum for discussing antibiotics in agriculture, as it accounts for about 80% of world meat production. An agreement to restrict or ban agricultural use is something the report recommends. ‘There is need for an agreement to phase out use of antibiotics as growth promoters in agriculture,’ says Røttingen. ‘But those sorts of measures can be put onto a negotiating table alongside financial incentives.’

Finding funds

To achieve any of these ambitious targets hard cash is needed. The Global Innovation Fund to support basic and non-commercial research in drugs, vaccines and diagnostics suggested in a previous O’Neill report will cost perhaps $2 billion over five years, while market-entry rewards on the order of $800 million to $1.3 billion for a new antimicrobial is costed at $16 billion over 10 years. Rolling out existing and new diagnostics and vaccines, which can cut antibiotic use, is put at $1–$2 billion per year.

‘The costs of action are relatively minor compared to inaction, but in the resource constrained world we live in the costs mentioned are not negligible,’ says Aurelia Nguyen, director of policy and performance at GAVI – The Vaccine Alliance. ‘Fund raising is going to be a big challenge.’ GAVI is cited over and over in the report as paragon of action, a public–private partnership that has helped to immunise 500 million children and save 7 million lives.

One funding suggestion is to allocate a small percentage of G20 countries’ existing healthcare funding to tackle AMR, while another is to take the cash from international institutions. A sales tax on the pharmaceutical industry has also been suggested. Finally a tax on antibiotics is proposed. Røttingen says a tax on antibiotics would work well in agriculture as it would reduce antibiotic use while providing funding to search for new ones.

Positive signs

‘These recommendations may well provide the roadmap to reversing the rising threat of antimicrobial resistance, which already claims hundreds of thousands of lives each year, but it will be what happens next – the global response – that shows its real value,’ says Philip Driver, senior programme manager at the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC). ‘Whilst the chemical sciences will be pivotal in research efforts to address the threat of antimicrobial resistance, success will depend upon an interdisciplinary, multi-sector research effort.’ He notes that the RSC is a member of the Learned Societies Partnership for Antimicrobial Research that brings together 75,000 scientists to tackle AMR in this exact spirit.

There have been promising developments in the fight against AMR. The World Health Organization and a number of countries have recently launched surveillance programmes to track the spread of antibiotic resistance. Support for companies’ R&D efforts is gaining traction too, with programmes like the Innovative Medicines Initiative’s ‘new drugs for bad bugs.

‘We’ve seen a much greater focus on this problem at national and international fora over the last five years and on Capitol Hill,’ says Boucher. ‘I’m going to a big meeting in a month or two on Capitol Hill with Lord O’Neill. There will be a number of substantial announcements, some in terms of investment.’

O’Neill himself signposts the G20 meeting hosted by China in September. ‘It is in China’s power to lead the world in tackling the AMR problem meaningfully and globally from their presidency onward,’ he writes. Whether the G20 has the collective will to take AMR remains to be seen. ‘How to politically convert [the report] into an agreement and how to implement it – those are the main challenges, which in many ways the review has not addressed,’ Røttingen says.

No comments yet