Gas chromatography reveals legs belong to one of Egypt’s lost queens

A pair of mummified legs in an Italian museum may belong to the ancient Egyptian Queen Nefertari, chemical analysis has revealed.

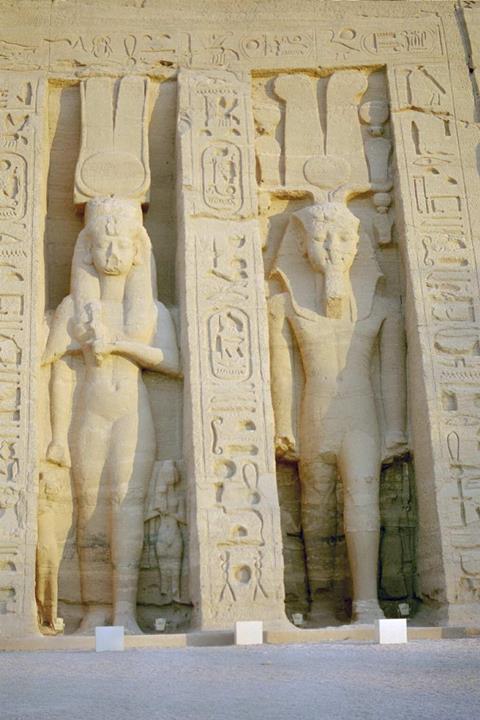

Queen Nefartari’s tomb was first excavated in 1904 and is the largest in the Valley of the Queens. Adorned with vivid and colourful artworks, the tomb serves as a monument to the wife of Ramses the Great – arguably the most powerful pharaoh in Egyptian history.

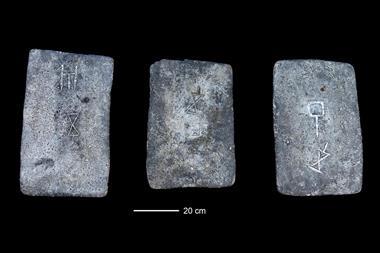

But looters had plundered tomb QV66 long before it was excavated by Italian archaeologists, with the remaining relics sent to the Egyptian museum in Turin. Among the treasures was a pair of linen-wrapped legs – the left broken into two parts.

Although they were found in QV66, the legs were not attributed to Nefertari, given they could have been part of a later internment. Now a team including Stephen Buckley, an archaeological chemist from the University of York, UK, and the University of Tubingen, Germany, along with the famed Egyptologist Joann Fletcher, has identified the legs’ owner.

The group first exposed the legs to x-rays to confirm they were from a human body. To get an idea of the body’s sex and height, the knees were compared to other ancient and modern specimens. This was followed by a chemical analysis of the outer wrappings to establish the mummy’s age.

Buckley and his colleagues used gas chromatography to identify the compounds present in the embalming agents employed during the mummification process. ‘The analysis revealed the same acyl lipid (fat) profile for all three parts of the knee assemblage, which is consistent with the three parts belonging to the same individual,’ says Buckley. ‘The chemical “fingerprint” suggested a non-human animal fat, which is what would be expected from the outer wrappings of the elite during the New Kingdom when Nefertari is known to have lived.’

Buckley goes on to explain that those tasked with mummifying a royal figure would often use animal fats to ‘convey important political or religious symbolism’.

The team also used radiocarbon dating to corroborate their chemical analysis. ‘Combined with the radiocarbon dating and the methods of mummification it points to an early 19th Dynasty date for the “mummified knees”, which fits with the fact that they were found in Nefertari’s tomb,’ comments Buckley.

References

M E Habicht et al, Plos One, 2016, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166571

No comments yet