Cheap and fridge-stable candidate at least 60% and up to 90% effective at preventing disease

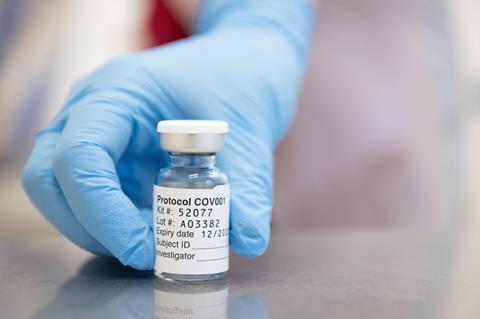

Interim results from phase 3 trials of the Covid-19 vaccine from the University of Oxford and AstraZeneca suggest it will provide good protection, although there are large differences between performance of the two tested dosing regimens.

The analysis was based on 131 Covid-19 cases among 24,000 participants in the UK, Brazil and South Africa. Most trial volunteers in the vaccinated group (8895) received two full doses of the vaccine, 28 days apart. This group had a 62% reduction in cases of Covid-19, relative to the placebo group. However, a smaller group (2741) received half the standard dose initially, followed by a full booster dose after 28 days, and showed around 90% efficacy. There were no hospitalised or severe cases in anyone who received the vaccine.

The Oxford vaccine relies on a chimpanzee adenovirus vector to carry DNA to cells to make the spike protein of Sars-CoV-2. The team describe adenovirus vaccines as stable, easily manufactured and capable of being stored at domestic fridge temperatures. This should make it easier to scale up and distribute than the vaccines from Pfizer–BioNTech and Moderna, which both reported interim analyses of their vaccines in the past two weeks.

I believe that we’ll eventually have at least a half-dozen good vaccines

AstraZeneca will manufacture and distribute the vaccine on a not-for-profit basis for the duration of the pandemic, and in perpetuity to low- and middle-income countries. The company has scheduled capacity to make 3 billion doses during 2021.

‘It’s very good news,’ comments vaccine scientist Peter Hotez at “Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, US. ‘I believe that we’ll eventually have at least a half-dozen good vaccines.’ He adds that ‘the Covid-19 spike protein is proving to be a “soft target” such that vaccines inducing virus-neutralising antibodies and T cells will work’.

Gregory Poland, vaccine scientist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, US, expresses caution about over-interpreting the 90% efficacy figure from the smaller subgroup before the full details are available. However, he offers a possible explanation for the difference in performance. ‘If you get the full dose, you [could] develop antibodies against the adenovirus carrier,’ he suggests. That way, the booster dose might be intercepted by the immune system, rather than actually delivering the vaccine DNA, ‘so you are actually not getting boosted in the same way.’

This is a vaccine that can be used across the entire world, particularly low- and middle-income countries

Hildegund Ertl at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, US, agrees that this is one of two likely explanations. The second is one she has seen in mouse studies. A higher dose of adenoviral vector means the vector producing the antigen (in this case the spike protein) will remain in their system for longer. The higher the adenovirus dose, the longer it takes antigen to clear. ‘As long as you have antigen, the immune system does not transition into memory,’ says Ertl, and it is this memory that a second dose boosts.

The Oxford press release noted an observed reduction in asymptomatic infections, suggesting that the vaccine possibly reduces transmission of the virus. Phase 2\3 results published in the Lancet showed the vaccine inducing a strong antibody and T cell immune response across all age groups, including older adults.

Clinical trial data has been sent continually to various regulators such as the European Medicines Agency, according to Adrian Hill from the Oxford team in a radio interview. Hill hopes to see ‘approval before Christmas and first vaccinations next month’. The team will now also apply to the World Health Organization for authorisation of an accelerated pathway to distribute the vaccine in low-income countries.

People’s willingness to continue mask wearing and distancing will matter

Statistical epidemiologist Stephen Evans at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK, says the Oxford vaccine compares favourably in terms of cost and logistics, since it only requires refrigeration at 2–8°C, rather than –20°C or –80°C for Moderna and Pfizer–BioNTech’s vaccines. ‘This is a vaccine that can be used across the entire world, particularly low- and middle-income countries,’ he says.

Poland warns that the 90% efficacy rates reported for Covid-19 vaccines are not fixed. ‘People’s willingness to continue non-pharmaceutical interventions like mask wearing and distancing will matter,’ he explains. ‘It will be a profound misinterpretation for people to think [they are] going to get the vaccine and not do any of this anymore.’

For all the vaccines, questions of durability and long-term safety remain to be determined, Hotez observes. That information will emerge as vaccines are rolled out to millions of people. ‘There are plans to have good post-market surveillance,’ Evans says, which will clarify protection in the elderly and people with other illnesses. ‘If there are rare side effects with any of the vaccines, we wouldn’t know until it was on the market,’ says Evans.

The Oxford vaccine trials will continue and are expected to include just under 60,000 participants by the end of the year, including further trials in the US, Kenya, Japan and India.

Hill attributed much of the reduced timescale in vaccine availability to manufacturing. ‘[Companies] have been manufacturing at risk since the summer, and hundreds of millions of doses are now available, waiting to be used once we can get regulatory approval,’ he explained.

No comments yet