Antibody-drug conjugate specialist will fill Pfizer’s cancer pipeline

Pharmaceutical giant Pfizer has agreed to buy leading cancer drugmaker Seagen for $43 billion (£36 billion) in cash. The biotech, based outside Seattle, US, is one of the pioneers in antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs).

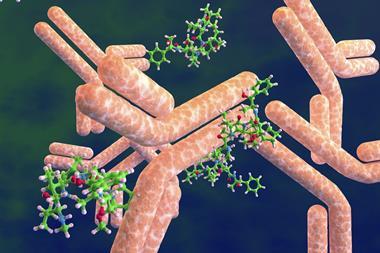

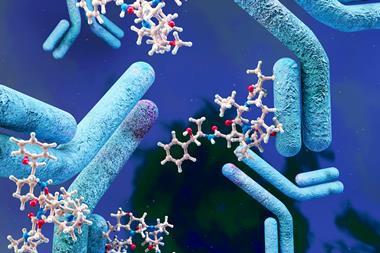

Most ADCs use a chemical linker to join an antibody, for tumour targeting, to a potent toxic agent, for killing cancer cells. This offers a more targeted approach than traditional chemotherapy, with greater efficacy and fewer side effects. ‘Oncology is the growth engine of the pharma industry,’ says Rachel Webster, market analyst at Clarivate, UK. By acquiring a pioneer and such a big player in ADCs, Pfizer will be able to drive future growth, she adds.

ADC approvals have accelerated significantly in the last five years. Nine have been approved since 2019, meaning there are 15 currently approved across major markets (one in Japan only, 14 in US and EU, of which one is being withdrawn for commercial reasons). There are another dozen or so in late stage clinical trials.

‘We forecast ADC sales will increase from $3.6 billion in 2021 to approximately $27 billion in 2031, across the major markets,’ says Webster. That growth will be driven by increased uptake of existing therapies, new approvals, and expansion of existing therapies to treat other cancer types and in wider patient populations.

Seagen has four marketed therapies, including three ADCs. The firm expects these to bring in $2.2 billion in revenue for 2023, but by 2030, analysts suggest that could grow to over $8 billion. Pfizer is more optimistic: ‘We believe Seagen could contribute more than $10 billion in risk-adjusted revenues in 2030,’ said Albert Bourla, Pfizer’s chief executive, during an investor call, ‘with potential significant growth beyond 2030, given the durability of the assets.’

Seagen’s three ADCs all feature monomethyl auristatin E as the cytotoxic payload, coupled to different antibodies. Adcetris (brentuximab vedotin) was approved in 2011 for treating lymphomas; Padcev (enfortumab vedotin) in 2019 for advanced and metastatic bladder cancer; and Tivdak (tisotumab vedotin) for cervical cancer in 2021. The small molecule kinase inhibitor Tukysa (tucatinib) was approved in 2020 for treating breast cancers where the HER2 protein is over-expressed, and for HER2-positive colorectal cancer in 2023. ‘Adcetris is a go-to drug for Hodgkin’s lymphoma and is already a blockbuster [with more than $1 billion in annual sales],’ says Andy Hsieh, market analyst at William Blair in the US. ‘Padcev is on track to be a blockbuster, while Tukysa has the potential to be a blockbuster, especially in targeting HER2-positive breast cancer.’

There is a scarcity of molecules that have mega blockbuster potential, so these become attractive assets for big pharma

‘HER2 has been a particularly successful target for breast cancer treatment,’ notes Webster. Two ADCs are licensed for HER2-positive breast cancer, while trastuzumab duocarmazine from Byondis is in phase 3. HER2 can also be a target for several other types of cancers.

Seagen’s pipeline includes 11 new molecular entities and a ‘wave of potential breakthrough medicines that could launch before 2030,’ noted Bourla. ‘We have additional opportunities for expansion of indications of these medicines, including early-stage bladder cancer, head and neck cancer and others,’ added David Epstein, Seagen’s chief executive, during the investor call.

Webster notes that several large pharmaceutical firms have recently acquired or partnered with ADC-focused biotechs. Bristol Myers Squibb teamed up with Eisai in 2021, Merck & Co struck a potentially multi-billion dollar partnership with Kelun-Biotech of China, while Merck KGaA, GSK and Janssen all have projects running with Mersana. Synaffix, which specialises in linkers and other technology to improve ADCs’ performance, has struck partnerships with biotechs including Genmab, Macrogenics, Emergence and Hummingbird, as well as bigger firms such as Amgen (which is also partnered with Legochem).

Gilead Sciences bought Immunomedics for $21 billion in 2020, partly to get hold of Trodelvy (sacituzumab govitecan), an ADC for triple-negative breast cancer. Last summer, Seagen was reportedly in merger discussions with Merck & Co. ‘Big pharma has been circling, with Seagen talked about as a target since 2010,’ says Hsieh.

‘There is a price premium for ADCs,’ he adds. ‘There is a scarcity of molecules that have mega blockbuster potential, so these become attractive assets for big pharma.’ ADCs’ allure is in stable and durable revenues. ‘They potentially have longer than expected market exclusivity,’ Hsieh explains. ‘The pathway for biosimilars has not been set, at least not in the US, and it could be very difficult to make copycat versions of such complex therapeutics.’

Pfizer’s coffers brimmed after over $100 billion in sales in 2022, supercharged by its Covid-19 vaccine (Comirnaty) and antiviral Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir–ritonavir). Meanwhile, patent exclusivity is running down on existing blockbusters, such as its blood thinner Eliquis (apixaban) and breast cancer drug Ibrance (palbociclib). Pfizer agreed to pay $229 per share, an almost 40% premium on Seagen’s before rumours of a takeover began.

No comments yet