A new see-through solar cell made from inexpensive silicon can generate useful levels of electricity from the light that falls on windows. The development avoids some of the problems of existing transparent solar cells, including high costs and the low levels of electricity they generate.

Most solar cells are opaque, and used mainly on rooftops and in outdoor installations. But researchers hope transparent solar cells can one day fill the vast building space now covered by exterior windows.

Contenders include dye-sensitised solar cells (DSSCs), which can be applied to windows as thin films. Other designs generate electricity from invisible infrared or ultraviolet light.

But these approaches have drawbacks, explains Kwanyong Seo of the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology in South Korea, who leads the lab that developed the new cells. DSSCs use often expensive or unstable new materials, which tint light red, green or blue. ‘We don’t want to show a colour, although it is very pretty,’ says Seo.

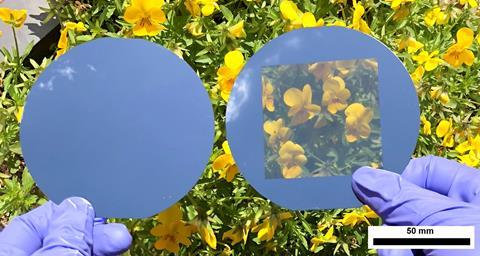

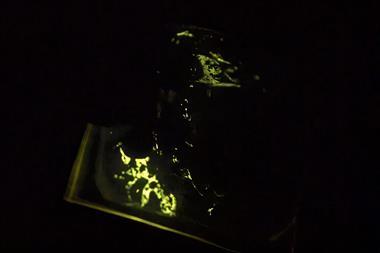

Seo’s solution is to engineer a conventional crystalline silicon wafer with tiny holes, about 100µm across, which are hidden from sight by spacing them at less than the minimum angular resolution of the human eye. The result is a neutrally-coloured, semi-transparent silicon solar cell. The darkest grade, which lets through 20% of light, has a conversion efficiency of 12.2%, Seo says.

That’s less than opaque silicon cells, which can have efficiencies of above 20%, but more than most transparent solar cells, which range from 5 to 7%.

Seo hopes the new solar cells can replace glass windows in houses and buildings. They are more expensive to make than ordinary silicon cells, but his team are experimenting with ways to reduce the cost.

The new cells also generate more electricity from low-angled light when they are installed vertically on windows: a fall-off of just 4%, compared with around 30% for traditional solar cells.

They have some drawbacks, however. The darkest cells absorb 80% of the incoming light, which corresponds to the darkest sunglasses, so a house might become rather gloomy if they were installed on every window, Seo admits. The researchers hope to improve the cells to make them more efficient, so that lighter grades can be used, he says.

‘For any semi-transparent cells there will always be a trade-off between transparency and efficiency,’ says Neil Robertson, who studies molecular materials and solar cells at the University of Edinburgh. ‘In this case the results look very promising.’

Robertson, who was not involved in the new research, notes the lightly-tinted solar cells shown in the research paper were probably not the most efficient. But the new cells appear to have advantages over some of the alternatives. ‘The proven stability of crystalline silicon cells and the neutral tint give good potential for practical application,’ Robertson says.

References

K Lee et al, Joule, 2019, DOI: 10.1016/j.joule.2019.11.008

No comments yet