Ben Valsler

Painkillers are vitally important in medicine. Not only do they help to make complex surgery possible, but they also allow people with chronically painful conditions to manage their symptoms and get closer to having a normal life. But they’re often something of a double-edged sword, with unpleasant side effects and the risk of addiction. Here’s Jamie Durrani.

Jamie Durrani

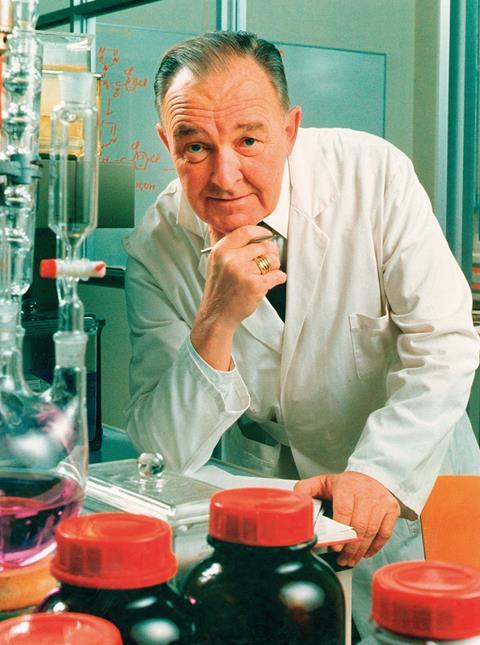

In the mid-1950s, the Belgian pharmacologist Paul Janssen began searching for the strongest painkiller possible. He believed that increasing the specificity of a drug molecule for particular receptors would avoid unwanted side effects and generally improve the safety of the drug.

The search led Janssen to synthetic opioids – a class of manmade drugs with similar therapeutic effects to the opiate compounds produced naturally in the opium poppy. In 1960, Janssen’s team found a compound almost 100 times stronger than morphine. That compound was fentanyl – now recognised as an important pain-relief medicine, but also implicated in the growing ‘opioid crisis’ and thousands of drug-related deaths.

Within three years of its discovery, fentanyl was being used clinically in Europe and was approved for medical use in the US in 1968. 50 years later, it features on the World Health Organisation’s List of Essential Medicines and is the world’s most widely used synthetic opioid.

When Janssen first synthesised it, fentanyl was the most potent and fastest acting opioid known to medicine. This was mainly due to its high solubility in fatty compounds, which allows it to more easily enter the central nervous system. It also stood apart from other anaesthetics due to its minimal impact on the circulatory system, and today intravenous fentanyl is routinely used during a wide range of surgeries.

Fentanyl is also prescribed as a treatment for ‘breakthrough pain’ – flares of severe pain that can be experienced by suffers of cancer and other conditions. For these treatments, fentanyl is often given via a patch that slowly releases the drug through the skin, or as a lozenge – usually a solid form of fentanyl citrate on a stick. These ‘fentanyl lollipops’ are also used by combat medics to bring quick pain relief to battlefield casualties.

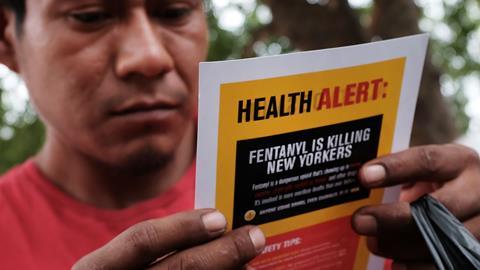

But despite fentanyl’s undoubted medicinal qualities, its strength and addictiveness make it susceptible to misuse. The last decade has seen an explosion in the number of opioid-related deaths, with the White House declaring a public health emergency in response. Between 2010 and 2016 in the US, the number of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids increased by more than 500%.

Scandals involving unethical marketing practises by pharmaceutical companies, and the prescription of fentanyl for off-label uses may have contributed to growing numbers of people gaining access to this powerful drug. Most significantly, the black-market trade in fentanyl is putting lives in danger.

Due to its relative cheapness, heroin dealers often lace or replace their product with fentanyl, putting at further risk users who may be unaware of the drug’s potency – a dose of just two milligrams of fentanyl can easily be fatal.

Demand for the drug in its own right is also growing, in part because of the ease with which it can be purchased on the internet. Researchers at the University of Oxford have found that the US accounts for nearly 40% of the global darknet trade in fentanyl, while the UK has the largest share of online sales in Europe.

Since it was first discovered, many new compounds based on fentanyl have been produced, several of which are even stronger than the original. Some of these have also found their way into clinical use, and many have entered illegal drug markets.

Perhaps one of the most tragic and controversial uses of fentanyl derivatives came during the 2002 hostage crisis at the Dubrovka Theatre in Moscow. During the incident, 40 armed Chechen terrorists stormed a sold-out performance of Nord-Ost, and held 850 people captive, including cast, crew and audience members. The standoff lasted for four days. Searching for a way to free the prisoners, authorities decided clear the way for a special forces raid by pumping an aerosol anaesthetic through the theatre’s air conditioning system. While the operation did manage to end the siege, with the majority of the hostages being rescued, around 125 people are believed to have died because of the effects of the incapacitating agent.

Russian officials never fully identified the chemicals used, but scientists at the UK’s defence research laboratory at Porton Down analysed samples of clothing and urine from rescued hostages, concluding they most likely comprised two synthetic opioids: remifentanil and carfentanil – the second of which is around 10,000 times more potent than morphine.

Despite its growing reputation as one of the world’s most dangerous narcotics, fentanyl continues to play a critical role in medicine. Its discovery vastly improved our understanding of the structure–activity relationships of pain relief compounds, helping to drive the development of stronger and safer drugs. And in recent years, fentanyl has been key to new innovations in drug-delivery technology, helping sufferers of chronic pain worldwide.

There can be no disputing fentanyl’s position as a vital medicine. It is truly an amazing compound, but with a serious dark side.

Ben Valsler

That was Jamie Durrani with synthetic opioid fentanyl. Next week, Katrina Krämer joins us with the antidote to opioid overdose.

Katrina Krämer

Price had overdosed on heroin in a public toilet and slipped into a semi-conscious state. The opioid was flooding his system, causing his breathing to slow. Had his friend not administered the life-saving antidote, he would have suffocated.

Ben Valsler

Join Kat next week. Until then, you can email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld with any comments or suggestions. Thanks for joining me, I’m Ben Valsler.

No comments yet