Meera Senthilingam

This week Simon Cotton shares one of his favourite experiments.

Simon Cotton

One of the perks of being a chemistry teacher is that you get to do great experiments. I suppose that it is about as near as you get to being a magician without being at Hogwarts.

One of my favourite experiments involves glycerol. First you crush some crystals of potassium permanganate to a fine powder, then you make it into a volcano-cone shaped heap, on a heat-proof mat. Just make a small dent in the top of the cone, then get a dropping pipette and slowly drip the glycerol onto it. After a few seconds, the mixture starts smoking and then it bursts into flames at the top.

Glycerol is not a hydrocarbon, of course, as it has oxygen in it, but you can explain that the carbon it contains is oxidised to carbon dioxide and the hydrogen is oxidised to water, in an exothermic reaction that is like a fuel being burned. Only here the oxygen needed hasn’t come from the air, it has come from the potassium permanganate, KMnO4.

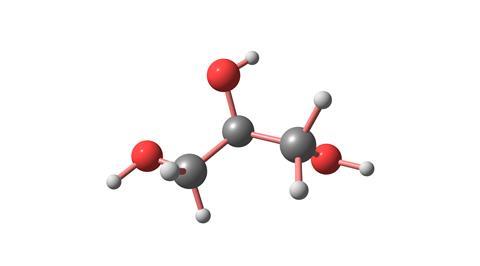

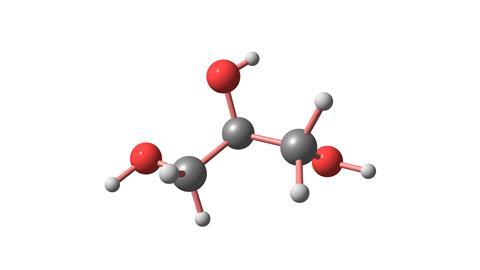

We normally meet glycerol as a rather syrupy colourless liquid, much more viscous than water or alcohol. The reason for this is that each of the three carbon atoms in the glycerol molecule has an OH or hydroxyl group attached. These three OH groups can bind to other hydroxyl groups, either in water molecules – which makes glycerol very soluble in water – or by hydrogen-bonding with other glycerol molecules. Hydrogen-bonding creates an aggregation that means that glycerol does not flow as well as water, so neat glycerol is rather viscous.

The ability of glycerol to hydrogen-bond with water means that when a glycerol-water mixture is cooled, it has to reach quite a low temperature before ice crystals start to form, and this is the basis of using glycerol in antifreeze for cars. Other polyols like ethane-1,2-diol (ethylene glycol) also do this – ethylene glycol is cheaper than glycerol, so that is the molecule usually used in antifreeze. Unfortunately, unlike glycerol, ethylene glycol is very toxic and regularly causes fatalities when children or pets drink antifreeze. Glycerol is very safe, and possibly the most risky thing associated with glycerol is its use in laxatives.

Glycerol is also an important chemical used to make various other chemicals, the best known being the explosive materials nitroglycerine and dynamite. Triacylglycerols (triglycerides) can be hydrolysed by boiling with alkalis such as sodium hydroxide to make soap, with glycerol as the other product.

But glycerol is most important to the functioning of our bodies. The human body stores glycerol as triglycerides in fat; these can be broken down to obtain energy, first by enzymatic hydrolysis back to glycerol and the fatty acids, which then can then be broken down further. Glycerol is converted to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, which in turn is converted into pyruvate, which enters the citric acid cycle.

Glycerol is a sweet-tasting, non-toxic liquid. This led to misunderstandings. One is that sweet tasting and toxic ethylene glycol gets confused with it (not least because of the similarity of the names glycerol and glycol). Another ‘polyol’ which is also viscous and sweet is diethylene glycol. It is also toxic, though less so than ethylene glycol. Because it is cheaper to make than glycerol, some unscrupulous – or ignorant – manufacturers have substituted it for glycerol in medicines and toothpaste. Notoriously, in 1937 a manufacturer used diethylene glycol to dissolve the drug sulfanilamide to make a cough syrup palatable to children, when over a hundred died. In 1985 some unscrupulous people added diethylene glycol to some Austrian white wines to make them appear to be more expensive white wines. In this case, no one was killed, apart from the Austrian white wine industry.

So always read the label on the bottle carefully, and don’t confuse other chemicals with glycerol, a sweet, harmless and extremely useful substance.

Meera Senthilingam

Birmingham University’s Simon Cotton, with the sweet chemistry of glycerol. Next week, the blessings of modern cleanliness.

Brian Clegg

Nowadays the whole business of personal hygiene is a gentle affair, a pleasant pampering with soothing creams and dermatologically tested soap substitutes. But go back a hundred years or so and keeping yourself clean and germ free was a rough, harsh world

Meera Senthilingam

Brian Clegg reveals why, and the compounds underlying this in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet