Meera Senthilingam

This week, a lifesaving compound. Nina Notman explains more.

Nina Notman

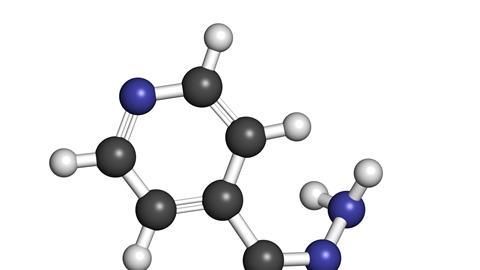

Isoniazid is a simple molecule containing a pyridine ring and a hydrazide. Its synthesis was first published in 1912 by two chemists working at the Charles University in Prague. While no doubt pleased with their discovery they couldn’t have had a clue how important their work would become 40 years later, when it was discovered to be an antibiotic suitable for treating tuberculosis (TB). Another 60 odd years on and isoniazid is still one of the cocktail of antibiotics swallowed by patients suffering from TB.

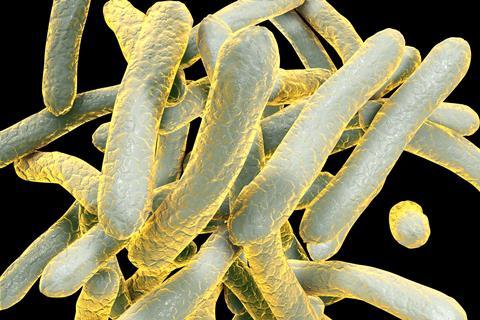

TB is a bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It usually affects the lungs but can attack other parts of the body. According to the World Health Organization, in 2012 an estimated 8.6 million people developed TB and 1.3 million died from the disease. India is one of the most severely affected countries with nearly 2 million people becoming newly infected with TB each year.

But TB is by no means a new illness. Hippocrates gave the first recorded description of the disease around 400 BC. In 1880 the bacterium responsible for TB was identified, and in the first half of the 1900s attempts were made to find a suitable drug to treat it. Both penicillin and prontosil – the first synthetic antibiotic – were found to be powerless against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. But with streptomycin came a glimmer of hope. However it was soon found that it did not work in all patients and the effect was often short-lived. Worse still, streptomycin-resistant TB soon became prevalent.

Then in the early 1950s, researchers from pharmaceutical firms Roche, Squibb, and Bayer came to realise independently – and in rapid succession – that isoniazid was active against TB bacteria. Not only that but it is specific to tuberculosis, having little effect on any other bacteria, fungi or viral species. All three firms rushed this antibiotic to market in 1952. It was not patented and the price soon became modest due to the competition between the three firms who were making it.

However that wasn’t the end of the battle against TB. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is difficult to treat, and isoniazid alone is not up to the job. Taking several antibiotics that each simultaneously attack the bacteria in different ways, over a long period of time, is the best way to beat the disease. TB in the lungs, known as pulmonary TB, is treated using a daily cocktail of antibiotics – including isoniazid – for six months. While a diagnosis of TB outside of the lungs normally leads to a longer, 12 month course of antibiotics. A mixture of medicines also makes it less likely that the bacteria will develop resistance to the treatment.

Unlike isoniazid, tuberculosis isn’t highly selective

In the first two months of treatment, a patient normally takes four different antibiotics, with the aim being to eliminate as many bacteria as possible. After this time only two of the antibiotics – one of which is isoniazid - need to be taken for a further four months to kill any remaining bugs.

There are growing concerns about antibiotic-resistant TB, but even so isoniazid has helped save many millions of lives. The UN states that treatments for TB saved 20 million lives between 1995 and 2011. Meanwhile the World Health Organization notes that the prevalence of TB had fallen by 37% globally since 1990 and the TB mortality rate had also fallen by 45% in the same timeframe.

I personally have reason to be grateful for the power of this simple molecule, as both my mother and I swallowed it daily for a year when we were inflicted with TB in the early 1980s. You see unlike isoniazid, TB isn’t highly selective. Yes it often attacks those starving in Africa, or those living in cramped conditions in India, and people with weakened immune systems caused by diseases such as HIV, but it can also be found in otherwise healthy individuals living in the innocuous suburbia of highly developed countries. So, if time travel is ever figured out you can see why my first stop would be 1912 to buy a pint for those two Czech chemists who just happened to make a molecule they rather liked the look of. A molecule that saved my life.

Meera Senthilingam

Science writer Nina Notman, thankfully living to tell the tale of Isoniazid, Next week, as things become festive – an affordable Christmas gift?

Phil Robinson

Two thousand years ago, frankincense and myrrh were as valuable as gold, the third gift of the Magi. But today, it will cost you a thousand times more to buy gold than to buy the same quantity of the other two.

Meera Senthilingam

Find out the chemistry devaluing these once sought-after compounds in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet