Ben Valsler

This week, Kat Arney finds out about a caterpillar chemical that will make your skin crawl.

Kat Arney

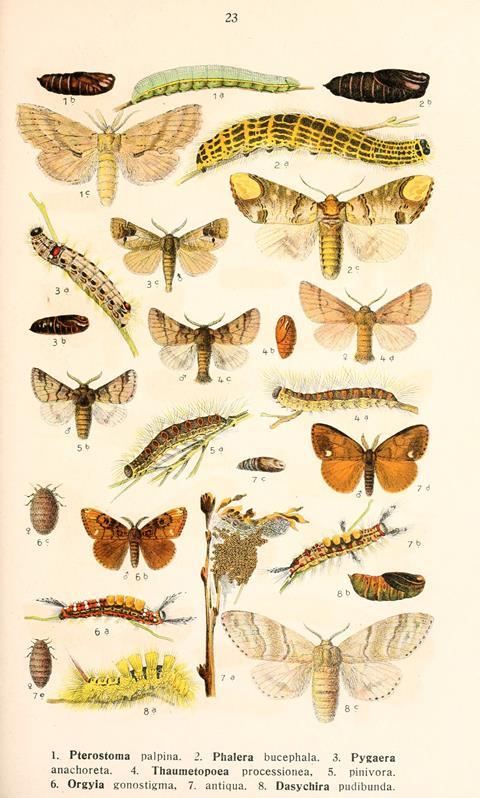

If you’re standing near an oak tree in the south of England and you spot a strange procession of hairy caterpillars wending their way along its branches, then stand well clear. They could be the offspring of the oak processionary moth, also known as Thaumetopoea processionea or simply OPM – an invasive species that hitched a ride to the UK from Europe more than a decade ago on an imported oak tree and set up home in London and nearby counties. In Mediterranean parts of Europe there is also a risk from caterpillars of a related species that lives on pine trees, known (predictably enough) as the pine processionary moth or PPM, which are also bristling with hairs.

While the formal name of these insects may mean ‘showing wonderful things’, they are far from wonderful themselves. In fact, they’re a downright hazard. Not only do the caterpillars pose a threat to our native oaks by rapidly stripping off their leaves, they are also a threat to human health – yes, these are the so-called ‘toxic caterpillars’ that have been in the news lately, responsible for triggering skin irritation, breathing problems, fevers, and eye and throat irritation.

In the most severe cases they can set off a major allergic reaction, known as anaphylactic shock, which can be fatal. It’s not just humans who are at risk: dogs encountering the caterpillars while nosing around near trees can suffer from severe skin or tongue irritation and may even suffer a fatal reaction. The first mention of these toxic critters goes back to ancient Roman times, and a specific law was apparently passed banning the use of processionary moth caterpillars in concoctions designed to break magical spells.

So how do these little creatures manage to be so terribly toxic? Their secret lies in their setae – tens of thousands of fine white bristles covering the caterpillar’s body that are packed with a toxic chemical known as thaumetopoein. These hairs are fired into the air in great quantities whenever a caterpillar feels threatened, or easily stick into an attacker that touches it (including unsuspecting children or curious pets). The hairs can even hang around and remain harmful for up to five years, posing a major health hazard in areas that might have been cleared of the pests.

The irritating properties of processionary caterpillars were first scientifically pinned down in the 1950s by French scientists who noticed that the creatures could trigger the release of histamine – a sure-fire sign of a nasty reaction. But finding the chemical culprit took several decades more.

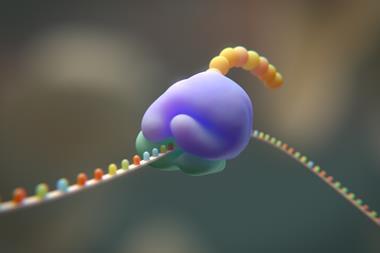

Thaumetopoein itself was first identified in 1986 by a team of researchers at the University of Bordeaux, France, studying the caterpillar. After mashing up the hairs, extracting the proteins and separating them by size, the researchers discovered a reasonably small protein, made up of two smaller subunits of around 15 and 13 kilodaltons, which is present in large quantities in the glands that produce the toxic hairs and provoked a reaction when tested on pig skin.

Unfortunately, this protein was never sequenced or analysed further. In 2003 a team of Spanish researchers took up the search again, using antibodies purified from the blood of people who had suffered an allergic reaction to PPM caterpillars to purify a 15 kilodalton protein – presumably one of the subunits of the original 80s thaumetopoein – which they called Tha p1. Nearly a decade later, scientists finally found what they presumed to be the second component – Tha p2.

Although a little work has been done looking at the genes that encode these proteins, particularly Tha p2, not much else is known about them. However, the whole genome of pine processionary moth was sequenced in May 2018, which will allow researchers to compare and contrast with genes in other moth species. Intriguingly, it appears that the reactions triggered by these hairy caterpillars may not be entirely down to thaumetopoein, as a recent study suggested that there may be many more proteins in the setae that could also contribute to the toxic effects.

While researchers get a wriggle on in the lab to find out more, there are a few things that you should do if you spot these toxic grubs on your local oaks. Obviously don’t touch or disturb them, otherwise you risk triggering a cloud of hairs. You should report any nests to the Forestry Commission who can send a specialist round to sort it out – don’t try and do it yourself, as it’s a job for professionals equipped with all the appropriate personal protective gear.

You might spot OPM caterpillars processing up and down trees in search of juicy leaves between April and July, but they will also move in crocodile formation from tree to tree across the ground, posing a risk to people and animals in their path. And the warmer weather in recent years has helped the OPM to gain a foothold and spread outside the capital into the surrounding suburbs.

Luckily the OPM remains restricted to a few places in London and the south-east, while its pine-loving relative hasn’t yet established itself in the UK, but the species are spreading north through Europe as the climate warms. Adult PPM and OPM moths have occasionally been blown here across the Channel so it may only be a matter of time – now that’s a thought to make your skin crawl.

Ben Valsler

That was Kat Arney with thaumetopoein and the oak processionary moth. And if you encounter some and have a mild reaction to their tickly hairs, you may want to consider next week’s compound.

Katrina Krämer

Scientists have long tried to figure out why some people’s bodies overreact this way, but as with many allergies, it’s an incredibly complex web of genetic and environmental factors. For now, doctors are left with instead treating the symptoms. Luckily, there is a huge range of compounds that do just that.

Ben Valsler

Katrina Krämer joins us next week with antihistamines. Until then, drop us a line with any questions or comments – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. Thanks for listening, I’m Ben Valsler.

1 Reader's comment