Ben Valsler

Whether you’re someone who loves amaretti biscuits or peels the marzipan from your Christmas cake and hides it under your napkin, you’re probably familiar with the taste and aroma of almonds. But, as Brian Clegg finds, chemists approach that aroma with much more caution…

Brian Clegg

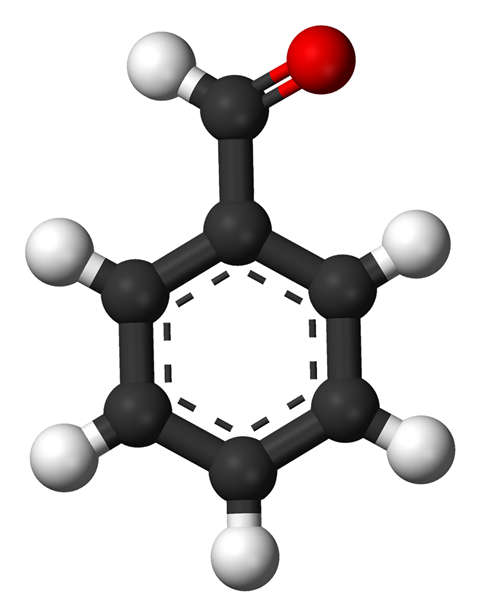

The intersection of almonds and chemistry is not always a happy one. Say ‘bitter almonds’ to a chemist and they will inevitably think of hydrogen cyanide. But what about the usual, delicate but distinctive taste of the nut? Here there’s a far friendlier compound at play: benzaldehyde, which turns up in a wide range of plants and is part of the complex aroma of coffee. Structurally, benzaldehyde is a simple benzene ring with an aldehyde unit attached – one atom each of carbon, oxygen and hydrogen. But this aromatic aldehyde has anything other than a simple odour and taste.

The vast majority of benzaldehyde in use is synthetic, though a small percentage is natural. It can be extracted from the variety of nut known as bitter almond (so-called as it has a significantly higher cyanide content than the usual variety), fruit kernels such as apricot and cherry stones, or a plant known as Chinese cassica. This contains cinnamaldehyde – the slightly more complex aldehyde that gives cinnamon its taste. The cinnamaldehyde is reacted to produce benzaldehyde. By contrast, the synthetic variety is usually produced from toluene, another simple aromatic compound found in crude oil.

The distinction between the two types of benzaldehyde is required for organic products (that’s organic in the marketing sense, not the chemist’s sense), where the synthetic compound is not allowed to be used. However, this distinction highlights the arbitrary nature of organic food standards: there is absolutely no chemical difference between synthetic and natural benzaldehyde. Chemically, they are exactly the same thing.

One source of benzaldehyde that isn’t often considered is human beings – yet we breathe it out in small quantities from the material we consume and from the breakdown of other compounds in the digestive system. And this could prove helpful when attempting to recover survivors of a disaster. A 2012 study at the Leibniz Institute for Analytical Chemistry in Hannover showed that human breath contained a range of chemicals, including benzaldehyde, which could be picked up by future detectors to alert a search and rescue team to signs of life.

If you like eating anything with almond flavour – think bakewell tarts, for example – you will have consumed benzaldehyde and taken part in by far the largest way that the compound is used commercially. Along with vanillin (you can guess the flavour there) it’s the most widely used aldehyde in food chemistry. It even gives almond hints to skin care products.

Because benzaldehyde is a simple aromatic compound building block, it is the starting point for the production of a range of compounds, in both the plastics and pharmaceutical industries. Fabric producers may have come across analine dyes that include benzaldehyde in their components, notably malachite green. And then there’s the matter of bees.

Not surprisingly, a number of compounds responsible for strong natural odours are either attractive or repellent to insects. In the case of benzaldehyde, it’s a turn-off for bees and is used as a repellent. Unlike, say, a mosquito repellent, this isn’t to keep them away from people but is used to get bees away from a honeycomb to be able to extract the honey. The benzaldehyde does the insects no harm, but the bees are unwilling to stay nearby. Flies have also been noted to reflexively jump when exposed to the compound.

Finally, benzaldehyde played a back-seat role in the discovery of one of our most widely used polymers. In 1933, researchers at ICI were attempting to react ethene and benzaldehyde at extremely high pressures. Instead of getting a compound of the two, the ethene polymerised to produce what would soon be known as polythene. It turned out that the benzaldehyde wasn’t involved in the reaction – the polymerisation was catalysed by some stray oxygen – but it was there at the birth.

Unless you are a bee, then, or dislike the smell and taste of almonds, benzaldehyde (whether natural or synthetic) is an excellent way to give your taste buds a treat. And in the future it may even help rescue survivors from a disaster.

Ben Valsler

That was Brian Clegg with benzaldehyde, one of the distinctive flavour compounds found in almonds. Next week, Michael Freemantle brings tears to our eyes.

Michael Freemantle

The British used the tear gas to flush enemy troops out of their entrenchments and dugouts and clear the field of battle, enabling its infantry to advance. The vapour was sufficiently powerful to force any soldier who was not wearing a gas mask out of a dugout within seconds.

Ben Valsler

Join Mike next week. Until then, get in touch with any questions, comments or compound suggestions. Email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld. I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

No comments yet