Meera Senthilingam

This week, Simon Cotton takes us to another world.

‘There is a world beyond ours, a world that is far away, nearby, and invisible. And there is where God lives, where the dead live, the spirits and the saints, a world where everything has already happened and everything is known. That world talks. It has a language of its own. I report what it says. The sacred mushroom takes me by the hand and brings me to the world where everything is known.’

Simon Cotton

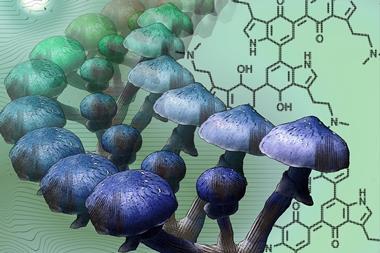

These are the words of Maria Sabina, a Mazatec shaman from southwest Mexico, describing the psychedelic effects of magic mushrooms. The Aztecs referred to them as Teonancatl, which meant divine flesh. It is said that guests at the coronation of the emperor Montezuma in 1502 ate these mushrooms to enhance their experience. After the Spanish conquest of Mexico, these activities were suppressed by the invaders but in the 1930s scientists discovered an active mushroom culture in the isolated southern province of Oaxaca.

In the mid-1950s, two Americans, Gordon and Valentina Wasson, got to know these Mexican people and were invited to take part in their mushroom rituals. They described the all-night services, when a shaman would chant for hours. Someone sampling the mushroom for the first time reported the sensation of being removed from their body and floating in space, experiencing richly coloured geometric patterns that grew into endless architectural structures.

There are several types of hallucinogenic mushrooms found in the area; the Wassons sent samples of the commonest, Psilocybe mexicana to the Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann. As the person who first synthesised LSD and an expert on hallucinogenic drugs, Hofmann was well placed to evaluate the mushrooms. He tested them on mice and dogs, but no clear result was forthcoming, so he tested samples on himself, and soon experienced a changing world. As he wrote afterwards:

‘Thirty minutes after taking the mushrooms, the exterior world began to undergo a strange transformation. Everything assumed a Mexican character … whether my eyes were closed or open I saw only Mexican motifs or colours. When the doctor supervising the experiment bent over me to check my blood pressure, he was transformed into an Aztec priest and I would not have been astonished if he had drawn an obsidian knife … The rush of interior pictures, mostly abstract motifs rapidly changing in shape and colour, reached such an alarming degree that I feared I would be torn into this whirlpool of form and colour and would dissolve.’

Analysis of the mushrooms revealed the active agent, a molecule given the name psilocybin, after the mushroom. Psilocybin is actually a prodrug, as once in the body it loses a phosphate group and is transformed into psilocin, the actual molecule responsible for the psychedelic properties of the mushrooms. Both psilocybin and psilocin contain a dimethyltryptamine group; their structures resemble serotonin, the brain’s natural neurotransmitter, and this suggests why they affect the brain.

A recent functional MRI study examined the brains of people injected with psilocybin, finding that it produced increased activity in the parts of the brain activated in dream sleep as well as more disjointed activity in the ego-system part of the brain.

Magic mushrooms and their psilocybin were not the only mind-altering substances known to Mexicans hundreds of years ago, as cults which involve the peyote cactus, Lophophora williamsii, and are centred around the south western United States and northwest Mexico go back even longer in time. Very recently European chemists and pharmacologists have carried out carbon-14 dating as well as chemical analysis on cactus samples found in ancient caves on the Rio Grande in Texas, and established they dated back to nearly 4000BC. They also found that the cacti did indeed contain mescaline as the active ingredient. Other mescaline-containing cacti are used in South America.

Mescaline was first identified in 1896 but was first made famous by Aldous Huxley in his 1954 essay The Doors of Perception, when he referred to:

‘…a slow dance of golden lights. A little later there were sumptuous red surfaces swelling and expanding from bright nodes of energy that vibrated with a continuously hanging, patterned light.’

It alters senses of vision, hearing, time and space. Mescaline’s chemical name is 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine, so it bears a structural resemblance to the amphetamines, but in addition the side chain can fold in such a way as to resemble the indole ring of psilocybin. Either way, it is expected to have effects on the brain.

In the 16th century a Spaniard who had studied its effects on the Indians of the desert plain of Mexico said that:

‘those who eat or chew it see visions either frightful or laughable … terrifying sights like the Devil. It sustains them and gives them courage to fight and not feel fear nor hunger nor thirst.’

They used it both medicinally and ceremonially. Like psilocybin, it was consumed in all night rituals involving dancing in a circle. Indians hunting for peyote make journeys resembling the pilgrimages of Western Europe as they head for the land where the cactus grows. Use of peyote even survived a ban by the Holy Inquisition in 1620.

American Indians discovered the cactus when they were in contact with Mexican natives, which spread a cactus cult in which peyote is used as a sacramental aid. They founded the Native American Church, which fuses native elements with Christianity, whose members are permitted to use peyote, containing a Schedule 1 hallucinogen – Class A drug in the UK - in their services. Practitioners of peyote religion are expected to abstain from alcohol, and indeed recreational drugs.

So there we have two hallucinogens which, unlike LSD, are natural compounds and which, moreover, have a rich history of ritualistic use across cultures and centuries.

Meera Senthilingam

Birmingham University’s Simon Cotton there, with the cultural and psychedelic chemistry of psilocybin. Next week, a life saving compound.

Anna Lewcock

The year is 1922. Fourteen-year-old Leonard Thompson is at death’s door. In desperation, his father allows doctors to inject Leonard with a new drug never before tested on humans. The results are staggering. Leonard quickly regains his strength, his appetite, and his life. All thanks to a modest molecule called insulin.

Meera Senthilingam

Anna Lewcock reveals the modest chemistry behind insulin in next week’s Chemistry in its Element. Until then, thank you for listening, I’m Meera Senthilingam.

No comments yet