Ben Valsler

It’s January. A new year and a new start – maybe even a new you? Perhaps you’ve started going to the gym, picked up the musical instrument you’ve lost the knack for or resolved to bake more often. And like that discount trial period at the gym, many people use this time of renewal and self-improvement to try out a lifestyle change. Dry January, where people give up alcohol for the month, has been growing in popularity – perhaps as an antidote to the festive excesses. And I, along with around 350,000 others, have signed up to veganuary – eschewing all animal based foods and adopting a vegan diet for the month.

Telling people you’re trying a vegan diet is a great way to get unsolicited – if well-meaning – nutritional advice, and the most common comment was to ensure I get enough vitamin B12. This is one of the very few nutrients essential to the human diet that is not made by plants at all, so it’s important for vegans to find an alternative source.

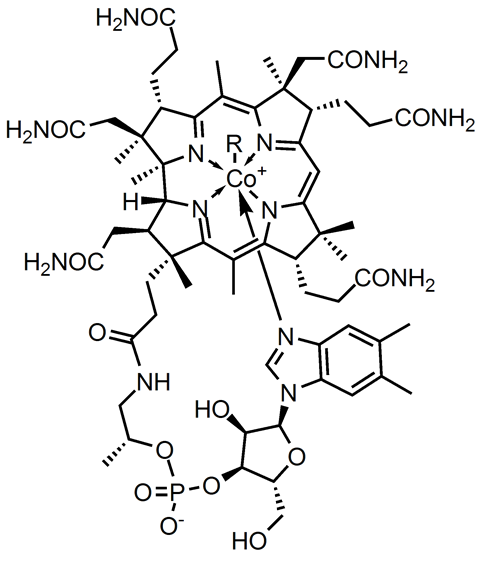

Vitamin B12, or cobalamin, is a group of compounds only synthesised by a few species of microorganism. There are a few different types of this vitamin, all with extremely complicated chemical structures, but common to them all and defining their familial relationship is a cobalt core at the centre of a haem-like ring. Their biological roles are equally complex: the cobalamins have a part to play as enzymes and coenzymes, helping the digestive system to absorb nutrients and aiding the production of both red blood cells and the sheaths that are wrapped around our nerves.

As such, deficiency can result in tiredness, anaemia, digestive problems and neurological impairment – you can see why my friends were concerned. Luckily for a toe-in-the-water vegan, the human liver handles the vitamin very efficiently – it absorbs about half of the B12 we ingest and stores enough to supply our recommended daily allowance (RDA) for around three to five years. Assuming I was well stocked in December, I certainly shouldn’t see any symptoms this month.

There’s some international disagreement about the RDA, however. In the UK, it’s 1.5µg/day. But in the US they note that a significant amount will be excreted before it can be absorbed, and set their daily value at 6µg/day. But consuming that much in one go may just result in nutrient-rich urine, as our ability to absorb B12 is limited by a protein called gastric intrinsic factor or GIF.

Produced in the digestive system, GIF binds to B12 and helps it to pass into the bloodstream. Normal human GIF production limits our B12 uptake to about 2µg per meal, so unless you spread your allowance out throughout the day, any extra just gets excreted. With this in mind, the US daily value is due to drop to 2.4µg in 2020. A lack of this intrinsic factor – due to genetic reasons or an illness like pernicious anaemia – can lead to B12 deficiency even if there’s plenty in your diet.

Carnivores, in theory, get their B12 from animal products. Liver and organ meat is the main source, with smaller quantities found in muscle tissue, eggs and dairy. An 85g serving of beef liver may contain 70µg of B12 (remember that the UK RDA is just 1.5µg), but the same amount of chicken breast contains just 0.3µg. Dairy fares slightly better – roughly 1.2µg in a glass of milk – and some seafood even more so: clams contain even more than beef liver.

Of course, this relies on the animal having sufficient exposure to the bacteria that make B12 – intensively farmed animals eating processed feed and treated with antibiotics actually have to be given the same sort of B12 supplements that vegans are encouraged to take. Meat may not be the answer in this case, as the Framlingham Offspring study, a long-term research project based on residents of Framlingham, Massachusetts, showed that B12 supplements, fortified cereal and milk all play a more significant role.

So where should vegans get their B12 from? Many cereals are already fortified, and supplements are readily available. The most popular suggestion seems to be nutritional yeast – a dried, deactivated yeast that lends a nutty, cheesy flavour to foods. This contains complete protein, meaning it contains all the essential amino acids the human body can’t produce, and is rich in other B vitamins, so a worthwhile addition to any diet. But nutritional yeast, or nooch, actually has to be fortified with B12 – yeasts are not among the select microorganisms that produce B12 naturally.

Will I stick to a vegan diet after January? I’m not sure. But I’ll certainly be more aware of where my B12 comes from, and will have some handy unsolicited dietary advice of my own for anyone who tells me they’re considering a vegan diet.

Next week, we’ll explore another cobalt compound – one you may have unknowingly used over the festive period if you had a glass of sherry.

Mike Freemantle

Harveys Bristol Cream sherry, for example, has been sold in distinctive Bristol blue glass bottles since the 1990s. Chemistry students may recall using cobalt blue glass in flame tests to filter out the bright yellow light of the sodium flame.

Ben Valsler

Join Mike Freemantle next week with cobalt oxide. Until then, let me know if there are any compounds you would like us to cover – email chemistryworld@rsc.org or tweet @chemistryworld.

You can find all of our previous podcasts and stay up to date with the latest chemistry news at chemistryworld.com. Thanks for listening!

Additional information

Theme: Opifex by Isaac Joel, via Soundstripe

No comments yet