Coronavirus trials reveal the murky reality of disentangling compounds’ effects on human biology

One side effect of the coronavirus pandemic is that the world outside of drug development research has been getting a painful real-time education on what the world inside drug research is like. Speaking as an inhabitant, I really wish we’d had a bit more advance warning of all the visitors; we surely would have made the place a bit more presentable for company. But in the end, there’s a limit to how presentable it can be.

That’s because people from outside medical research (and from outside science in general) have likely been expecting things to be quick, sure, sensible, and effective: the way that they are, by necessity, in one-hour television episodes. That makes sense for a screenwriter needing a plot point to resolve itself on time, but we’ve always been working off a different script. One of the hardest things to realise is that we have very little hand in writing that script, and very little say in what the next episode will be like. That’s frustrating, particularly if your worldview leans more toward having intelligence and self-confidence conquer all obstacles by the end of the third act, because reality doesn’t always care about how smart and dedicated we are.

When have you ever seen a show where the answer that the entire storyline hinges on turns out to be ‘Well, sort of. Maybe. We’re not quite sure?’

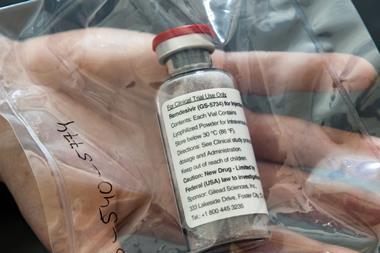

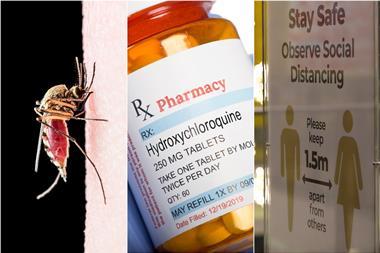

Look, for example, at the results that have been coming out of the clinical trials for possible therapies against Covid-19. When have you ever seen a show where a big, widely anticipated answer (does the drug work, or not?) is built up and foreshadowed while the entire storyline hinges on it, only to have the readout be ‘Well, sort of. Maybe. We’re not quite sure.’ And then right behind it arrives another trial that somewhat contradicts the first one, but perhaps not completely? Perhaps? Aspiring screenwriters, take note: do not attempt this level of realism, because no one will stand for it.

But that’s what things are really like. It is difficult even under ideal circumstances to design and run a clinical trial that provides definite, actionable data. Since that’s the whole purpose of such a trial, a great deal of effort goes into trying to arrange such a result. But under these pandemic conditions, it becomes nearly impossible. The number of patients isn’t what it should be, or the data collection can’t be thorough enough or regular enough, or there is simply no time or facility to do proper randomisation or double-blinding, etc. The chances of a trial giving useful results go down with every omission and every shortcut, and believe me, the people running it are well aware of this. It’s just that some data, quickly, might well be better under the current conditions than more data quite a while from now.

Does the drug work, or not? Well, it trended towards significance, and one of the secondary endpoints was better, although that one didn’t show any real effect in the other trial, even though both groups of patients seem roughly comparable (from all one can tell), but adverse events were higher in the first trial and not really a problem in the second…what is a journalist, a headline writer, or an interested reader to make of this? Why can’t anyone tell them the answer to that simple question?

It’s an ‘effect size’ problem, really. Onlookers want to see fevers suddenly breaking, people getting up out of hospital beds – they want to see cures, understandably! But most drugs, most of the time, don’t have effects large enough to do that by themselves. That’s especially true for antivirals, where the very few therapies that come close are cocktails of several carefully tailored compounds, each with its own mode of attack and years in the making. We will move into that territory against the coronavirus when we can enlist the powers of the immune system, via monoclonal antibodies and vaccines. A really effective vaccine can make a disease disappear to the point that people forget what it even looked like and it becomes a name out of old stories. That is exactly where we would all like to relegate the Covid-19 epidemic, but until those two technologies find their range and start firing, we will likely be seeing a lot of partial, hazy, semi-victories that will raise few flags and ring only muffled bells.

No comments yet