4.30pm And that’s where we’ll leave it today

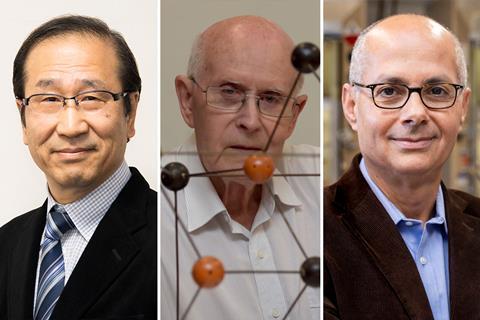

Thanks for joining us today to celebrate the Nobel prize in chemistry. Kitagawa, Robson and Yaghi are all deserving winners and MOFs are a solid choice from the Nobel Committee, one that has been just waiting to win a prize for some years now. Don’t forget we’ve got a free hour-long webinar at 3pm on Friday 10 October where we’ll be talking to special guests about the award (last year we were lucky enough to get newly minted laureate David Baker). Next week we’ll also be bringing you a deeper dive into the prize and its winners.

3.08pm Still have questions? We’ve got answers

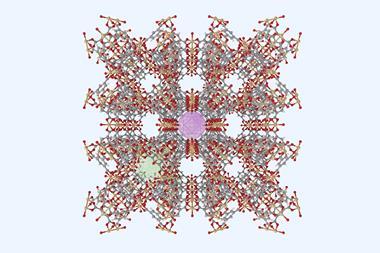

Are you still unsure what exactly a metal–organic framework is? Why is the discovery and development of MOFs worthy of a Nobel prize? What did Kitagawa, Robson and Yaghi all contribute to receive the prize? And are these materials finding any use in the real world? We break down today’s prize for you and explain it all.

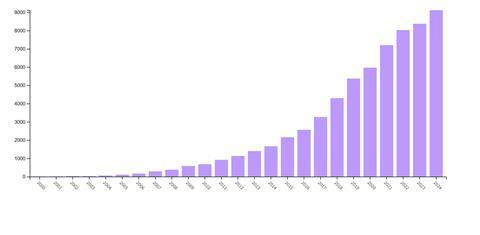

2.54pm The rise of MOFs

We saw earlier how MOFs now make up a significant proportion of the structures submited to the Cambridge Structural Dabase. Now, we can look at the number of publications that feature MOFs in a search of the Web of Science database. Omar Yaghi coined the term metal–organic framework in 1995, but it took some time for wider interest in these structures to take off.

2.39pm Talking all about MOFs

On Friday 10 October at 3pm BST, we’ll be hosting a free to attend hour-long webinar talking about the recognition of Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar Yaghi with the 2025 Nobel prize in chemistry for their work on MOFs. We’ll be joined by special guests as we discuss why these three won the prize, who might have been overlooked, the development of the field of metal-organic frameworks and what challenges MOFs are set to tackle.

2.31pm More r

The Royal Society of Chemistry has also released a collection of important MOF papers following the announcement.

2.08pm The new laureates’ family trees

Earlier we examined the academic ‘family trees’ of the winners of the medicine and physics Nobel prize. We looked at who mentored them, their ‘parents’, and who they’ve mentored, their ‘children’ noting that laureates often have researchers who were themselves Nobel prize winners in their lineage. Looking at Susumu Kitagawa, his ‘parent’ was F Albert Cotton, a giant of transition metal chemistry who won many prizes that predict a Nobel might come your way but he never received the call from Sweden. Kitagawa’s academic ‘grandparent’ was Geoffrey Wilkinson, who did win the chemistry prize in 1973 for his work on sandwich organometallic compounds, such as ferrocene. One of Kitagawa’s great grandparents was Glenn Seaborg, who of course won the 1951 chemistry Nobel for his work on transuranic elements.

Richard Robson can boost Nobel laureate lineage too, as Melvin Calvin is one of his ‘grandparents’ who won the 1961 chemistry prize for his work elucidating the Calvin cycle that plants follow to fix carbon. Among his great grandparents you’ll find Robert Robinson, who won the 1947 chemistry prize for work on natural products.

Interestingly, F Albert Cotton is also among Omar Yaghi’s ‘family tree’. However, unlike Kitagawa he wasn’t mentored by him but counts him among his ‘grandparents’. This means he boosts the same Nobel laureates at Kitagawa but a generation further removed.

1.34pm Interview with Omar Yaghi out

The Nobel Committee managed to catch him between flights!

“My parents could barely read or write. It’s been quite a journey, science allows you to do it.”

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 8, 2025

New laureate Omar Yaghi was in the middle of changing flights when we reached him, just after he heard that he had been awarded the 2025 #NobelPrize in Chemistry.

In this interview… pic.twitter.com/pTlHPdX4st

1.20pm More reactions to the announcement coming in

Annette Doherty, president of the Royal Society of Chemistry said: “I add my congratulations to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar Yaghi on this well-deserved recognition – your work reflects the best of what chemistry can do: connecting people, ideas and discoveries to change the world for the better.

“Metal organic frameworks are an incredible group of materials, which have fantastic potential in a range of applications – from gas storage and separation to carefully targeted drug delivery and even removing pollution from the environment.

“Every year we see Nobel Prizes given to chemists who welcome the challenge of finding solutions to the biggest problems our global society faces – better healthcare, environmental protection, clean energy, and secure food and water for everyone. This year’s winners are a great example of that endeavour.”

Kim Jelfs in the Department of Chemistry at Imperial College London commented: “The work of the prize winners laid the foundation for a vibrant international field of research in novel metal-organic frameworks, and more than 100,000 MOF structures have been reported to date.

“The applications of MOFs all stem from their porosity – one gram of a MOF material can have the same surface area inside its pores as a football pitch.

“The field of MOFs all began with the research by Robson in the early 1990s who designed coordination polymers that could be engineered to have pores.”

David Pendlebury, Head of Research Analysis at the Institute for Scientific Information at Clarivate said, “We are delighted to see Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson, and Omar M. Yaghi recognized with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for their pioneering work on metal-organic frameworks.

We named Kitagawa and Yaghi Citation Laureates in 2010, based on their exceptional citation records in the Web of Science — a clear signal, even then, of their profound influence on the field. Their highly cited papers reflected a rapidly expanding area of research, already two decades in the making at that time. Notably, both have been named Highly Cited Researchers every year since 2014, demonstrating that their contributions have not only stood the test of time but have continued to shape and lead the field as it has grown.’

Becky Greenaway in the Department of Chemistry at Imperial College London commented: “Lots of chemists have been wondering when metal-organic frameworks would get the Nobel Prize, and it’s finally happened!”

“Their discovery has enabled a whole range of applications, from gas storage and separations to drug delivery, and also opened-up other areas, including porous liquids – liquids with holes in - which are showing promise in carbon capture and catalysis.

“They are already seeing commercial use, for example, for carbon capture from flue gas, keeping fruit fresh, and for storing reactive gases for the semi-conductor industry. They also have potential for water harvesting - for example they are being trialled in the desert for collecting clean water from the air. You can only imagine that their use in real-world applications would continue to expand in the future.”

12.57pm The news is out

You can read our news story on how the Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar Yaghi came to win chemistry top gong. It’s a fascinating history of the development of these materials, showing how each scientist built on the others work.

11.35am Predictions can come true

Omar Yaghi has been tipped for some time for the chemistry Nobel prize. As one of the pioneers of this important class of materials he’s certaintly had a big impact in this field. We noted earlier today that Yaghi was voted for by quite a few people in a recent poll on who might win. Kitagawa’s name has come up often too, appearing on ChemBark’s authoritative list. Kitagawa and Yaghi were both 2010 citation laureates – so that can be considered another success for Clarivate’s ISI, when it comes to recognising the most important research and the scientists that are doing it. Richard Robson seems to be a darker horse and not a name I remember coming up with regard to a Nobel prize that recognises MOFs. He wasn’t a citation laureate alongside Kitagawa and Yaghi either, hasn’t won the RSC’s Centenary Prize (Yaghi has), The Wolf Prize in Chemistry (Yaghi has too), or won any of the other big chemistry prizes that I can see. He is a fellow of the Royal Society though.

11.28am Reactions coming in!

Time to break out this pic of me being strangled by a future #Nobel Laureate in 2017… #Chemsky #chemnobel…

— Stu Cantrill (@stuartcantrill.com) October 8, 2025 at 11:23 AM

[image or embed]

What happened? Did you reject one of his papers?!

I'm still shaking!

— Stuart Batten (@sbattenresearch.bsky.social) October 8, 2025 at 10:58 AM

11.15am Chatting to the laureates

MOFs have been a huge topic for us over the last 15 years – we have over 170 entries for them and they really have been a very important chemistry topic. Consequently, we’ve got a few interviews. We spoke to Susumu Kitagawa back in 2017. Truly functional MOFs are on the horizon but Susumu Kitagawa saw their potential when they were weak and idle. Clare Sansom caught up with him at the 24th Congress of the International Union of Crystallography in Hyderabad.

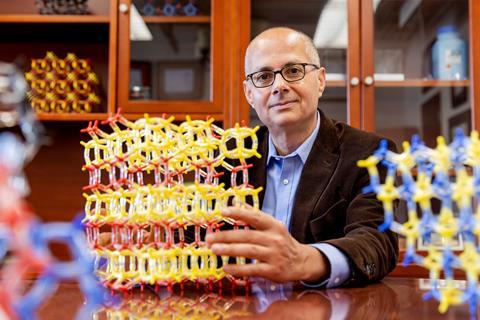

We had a personal interview with Yaghi in 2019 and he told us he was in love with chemistry and that work was his hobby.

11.05am The incredible rise of MOFs

In 2019, we were celebrating the Cambridge Structural Database hitting one million recorded structures. We worked with data from the CSD to create a range of infographics detailing how the types of structures submitted had changed over the years. This highlights how research into MOFs really took off in the 2010s. The data ends at 2018, but if it were updated I’m certain that the number of MOFs would have continued to rocket, potentially even becoming the most submitted structures to the database. That’s something we’ll see about following up with the CSD.

10.59am We spoke with Yaghi earlier this year

Omar Yaghi outlined his excitement with MOFs and how he was getting behind a new institute that would employ AI in this area.

10.49am We have three new chemistry laureates!

Congratulations to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar M. Yaghi who win the chemistry Nobel for their development of metal–organic frameworks – MOFs. They’ve been tipped for quite a while now and it seemed a question of if, not when MOFs would win. Well deserved winers. The only question was whether MOFs had demonstrated enough of that ’greatest benefit to humankind’ yet that the Nobel Committee looks for – the committee can wait decades to reward such discoveries. The Nobel Committee has decided they now have and that’s a win for supramolecular chemistry. MOFs are created by combining a metal with organic linkers to create a cage like structure, something that has made them very interesting for storage of gases. MOFs are remarkable for their huge surface area and the incredible diversity of materials that can be created.

10.45am Showtime!

The name cards are going out for the chemistry Nobel panel…

10.36am Chemistry across borders

An inspirational quote from Ben Feringa, the 2016 chemistry Nobel laureate for his work on molecular machines. Fraser Stoddart, who Feringa shared the prize with, died on 30 December 2024.

10.32am Watch live

The feed from the press conference has just started rolling.

10.31am We’ve just been told…

…that things are running on time and we can expect the announcement at 10.45am BST.

10.30am Just 15 minutes to go…

…should everything go according to plan and they can contact at least one of the winners.

10.25am Will an AI ever win a Nobel?

When will an AI-generated discovery win a Nobel prize? You might think that with last year’s physics prize going to machine learning pioneers, and half of the chemistry one going to AlphaFold, it’s almost already happened. But of course those prizes were for the work developing the AI or machine learning systems, rather than anything those systems produced. This news feature in Nature talks to the scientists using AI in their research, and to judges in the Nobel Turing Challenge, which aims to reward Nobel-level machine-generated science.

10.22am A prize better than the Nobel

If you’ve been fantasising about your Nobel acceptance speech this morning, don’t forget to keep other career paths in mind as well. As he completed his PhD, Sohaib Sadiq anticipated that he’d set off on a career path that would see him revolutionise biochemistry. But when he eventually secured his first postdoc position after a year of applying, it was the non-technical aspects of his role – mentoring, lab management, maintaining morale (and laughing at his mistakes – don’t put a plastic flask in the autoclave!) – that appealed the most. He’s now thriving as a research technician at the University of Leeds, UK. As Sadiq reflects: ‘scientific success isn’t measured only in papers or prizes, but in persistence, adaptability and the ability to lift others along the way’.

10.20am Satirical chemistry Nobel…

Very topical.

BREAKING: the 2025 Noble Prize in Chemistry has been awarded to DuPont, 3M and Daikin “for the development and deployment of PFAS: a family of infinitely sustainable chemicals”. As these now-ubiquitous chemicals never decompose, they can be reused for generations to come. pic.twitter.com/JCrvHB655L

— The Journal of Immaterial Science (@JImmatSci) October 8, 2025

10.17am Beyond selfies with Nobel laureates

The Lindau meeting that takes place every year in Germany brings together dozens of Nobel laureates from around the world. There, they give presentations and meet the younger generation of up and coming scientists. This year, Edgar López López, a drug discovery chemist from Mexico who attended the meeting, makes an impassioned please to these laureates – work with and uplift young scientists to help them tackle the big challenges that the world faces.

10.13am A love letter to the Nobel prizes

The Nobel prizes have come in for a lot of stick in recent years. Admittedly the prizes do have their problems, many of which date back to their setting up and the rules which govern them. Despite all their issues, I think they’re still second to none for highlighting the difference that science can make to the world, and have penned a paean in praise of these prizes.

10.08am Immigration’s link to the Nobel prize

The US has been a scientific powerhouse since the end of the second world war and this can be seen in the number of Nobel prizes in the sciences its researchers have won. In all, the US has won 319 Nobel prizes since the awards began and 112 of these were awarded since 2000. Now, however, the Trump administration is putting the US’s scientific pre-eminence at risk with its attacks on the scientific establishment, firing of workers at science agencies and hostility to immigration. (One of this year’s physics laureates, John Clarke, warned last night that the Trump administration’s actions will ‘cripple much of United States science research’.)

The US has greatly benefitted from skilled immigration over the years and this can be seen in its Nobel prizes winners, 40% of whom have come from overseas, according to one analysis. The graphic below reveals how post-second world war far more chemistry Nobels were awarded to researchers working in the US, revealing where the winners were born and where they were working when they won their prize (one of the few researchers in recent times going against the trend of moving to the US to do their Nobel-prize winning research is 2024 chemistry laureates John Jumper, who moved to Google’s AI division in London). The direction of travel is currently clear but as political winds shift and support for science dries up in previous research powerhouses new patterns may emerge and a shift in focus to China seems entirely plausible in the coming years.

9.59am Colouring chemistry’s greatest discoveries

If you’re feeling artistic after that last post and are a fan of colouring, or know someone who is, then this book is for you. Vittorio Saggiomo, a chemist at Wageningen University, has created a set of three beautiful colouring books featuring the discoveries rewarded by every single chemistry Nobel prize since 1901.

And here we are, the first book live on Amazon. A "Nobel in Chemistry coloring book" :D All 116 Nobels (3 books) have been hand-drawn and are ready to be colored. Part 2 is on its way, and Part 3 will be released after this year's Nobel Prize. www.amazon.com/dp/B0FRF39YS4 #chemsky #nobel

— Vittorio Saggiomo (@vsaggiomo.bsky.social) September 18, 2025 at 1:25 PM

[image or embed]

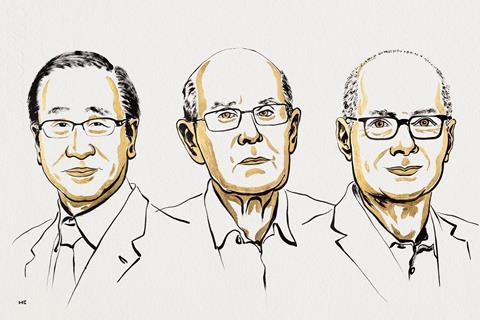

9.56am Noble illustrations

What’s the story behind those distinctive illustrations of the laureates that accompany every Nobel prize? Official artist of the Nobel prizes Niklas Elmehed talks about how he brings these portraits to life with black acrylics and metal foils.

9.54am ‘You mean I have to stop my experiment? I’m kind of busy’

How do Nobel laureates react when they’re told that they’ve won a Nobel prize? Unsurprisingly, reactions vary rather a lot. The kind of response above is purportedly how Konstantin Novoselov, who won the physics prize in 2010 for work on graphene, felt when he realised his life was about to be upended by winning science’s most prestigious prize. Adam Smith, who says he has spoken to more Nobel laureates than anyone else alive as chief scientific officer at Nobel Prize Outreach, recalls 18 years of talking to laureates just after they’ve received the call from Stockholm.

9.52am A dying breed?

Earlier, we were looking at the stats for the chemistry prize and noted that of the 116 prizes awarded, 63 were unshared – these prizes were won by a single person on their own. Running up a quick graph of the number of solo chemistry laureates in each decades the trend is pretty clear. It seems likely that a number of different factors are at play here, including the increasingly interdisciplinary and collaborative nature of science, far more scientists in each field making a single authority less likely and changes to what the Nobel committee is looking to reward. Untangling exactly what is behind this trend would be extremely difficult, but one thing is clear – solo laureates are a dying breed in chemistry.

9.47am You may not win a Nobel prize, but you can dine like a laureate!

The banquets that follow the presentation of the Nobel prizes are famed for their extravagance. This goes for the desserts too that for many years were a confection of ice creams served with great aplomb by waiters bearing pyrotechnics while singers serenaded the diners. These pudding parades were apparently regarded with almost childlike wonder by Nobel prize winners, so grand was the event, and many still list this as one of the highlight of their visit to Sweden to collect their prize. This article (admittedly a few years old now) goes into the amazing history of the ice cream bombes routinely served at yesteryears Nobel banquets, which have now diversified their dessert delicacies, and how to make your own dessert fit for a Nobel laureate.

One of last year’s winners of the medicine Nobel prize, Gary Ruvkun, would certainly have approved of the ice cream bombes once served. He celebrated in style last year by taking over his local ice cream van and handing out treats to all.

Hot fudge, strawberry or sprinkles? Gary Ruvkun isn't only a Nobel Prize laureate, he also helps out his local ice cream truck on occasion. Ruvkun visits the 'Frosty Truck' so often the owners consider him extended family.

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 13, 2024

The newly awarded medicine laureate celebrated his prize… pic.twitter.com/Q0V7fDt7NG

9.44am Just over an hour to go until the announcement

In 2023, by this time we knew who the next chemistry laureates would be due to a press release being sent out early to a Swedish newspaper by mistake. Oops. Unlikely to be a repeat of that this year.

9.36am End the simping over laureates

Nobel laureates are fallible humans just like the rest of us, writes Chemistry World comment and careers editor Emma Pewsey. She writes that we need to end the veneration of laureates as infallible geniuses and realise that their work is the product of a system that allowed them to try, fail and finally succeed.

9.29am Who’s having the most success predicting prizes?

As we’ve just seen, every year people like to make their predictions on who they think might win the chemistry Nobel prize. It’s a bit of fun that gets people engaging with whose work has been groundbreaking in recent years and has also had an outsized societal impact. While the Nobels might be the most prestigious science prizes, they aren’t the only prizes in town. Many of the others prizes take a less conservative approach to rewarding scientific achievement and don’t feel the need to wait years – it famously took around 40 years for the Nobel committee to recognise the inventors of lithium-ion batteries. Nobel prize-watchers often note that researchers that win high profile prizes such as the Wolf Prize in Chemistry are good indicators that a call from Sweden could on the cards for them. But which prizes and awards are the best indicators of future success? We’ve taken a look.

I think we can agree that with less than 25 years awarding its citation laureates and with 16 of them having gone on to win chemistry Nobel prizes the Institute for Scientific Information is playing a blinder by analysing the top performing papers and using a bit of expert judgment to pick their winners. We recently interviewed the head of the ISI to understand exactly how they go about selecting their winners.

Last year, we also looked at which prizes chemistry laureates had won before they received Nobel recognition.

9.23am Some more predictions from around the internet

#NobelPrize week starts tomorrow & the #chemnobel is Wednesday… used to be so much Nobel chat on Tw*tter, but that is not replicated here, alas. Anyway, for the record, I think MOFs will win at some point (maybe this year maybe not). Balasubramanian & Klenerman a good bet for next-gen sequencing too

— Stu Cantrill (@stuartcantrill.com) October 5, 2025 at 6:37 PM

Roberto Car and Michele Parrinello are on my #ChemNobel ballot for 2025 and for every year until they'll get it 😎

— Elisa Fadda (@elisafadda.bsky.social) October 6, 2025 at 6:09 PM

[image or embed]

It's soon #Nobelprize week ! My 2 cents 2025 prediction #mednobel J. Bloch & G. Courtine for restoring function after spinal cord injury #chemnobel S. Balasubramanian, D. Klenerman & P. Mayer for NGS #physnobel J. Navarro, C. Frenk & S. White for Dark matter #Literaturenobel M. Atwood

— Alexis Verger 🧬🧫🧪 (@alexis-verger.cpesr.fr) September 24, 2025 at 9:19 AM

9.17am Who will win the chemistry prize?

As the Nobel prizes capture the public imagination more than any other scientific award, predictions on who might win one is always a hot topic. Last year, the citation crunchers at the Institute of Scientific Information at Clarivate selected, among others, John Jumper, Demis Hassabis and David Baker as their citation laureates – highly cited scientists, a fair number of whom go on to win Nobel prizes. Jumper, Hassabis and Baker did indeed win the chemistry Nobel prize that very year for their work on protein prediction and design. This year’s selections recognise researchers working to create greener batteries, single-atom catalysts and understand biomolecular condensates.

At Chemical & Engineering News they hosted a webinar and panel discussion on 1 October where they invited their experts to make the case for who they’d like to win. While there were some predictions that might be familiar to readers, such as David Klenerman and Shankar Balasubramanian for their work on next generation sequencing or Krzysztof Matyjaszewski for the development of atom transfer radical polymerisation, there was one interesting new suggestion. Joel Habener, Svetlana Mojsov and Jens Holst were nominated for their work developing weight-loss and diabetes drugs that mimic the hormone glucagon-like peptide 1. These drugs will be familiar to many under their brand names Wegovy, Mounjaro and Ozempic. While I’m certain these drugs will win a Nobel prize at some point, I’ll leave it up to readers to decide whether this should be a medicine prize or a chemistry prize (although looking at the drugs’ structures it’s clear some pretty nifty chemistry went into their development).

The community poll on ChemistryViews has thrown up a few more names, some of which are also frequently tipped to be future winners. This year Herbert W Roesky, an inorganic chemist known for his work on transition and p-block metal fluorides, has received the most votes and is a virtual newcomer to the list receiving just a single vote last year. Chi-Huey Wong, who received over 90 votes, has been a regular on this list and has been tipped to win the chemistry prize for a few years for his work on complex carbohydrate synthesis. Omar Farha and Omar Yaghi are both regulars to this list and are a popular choice to win the chemistry prize for their work on metal-organic frameworks.

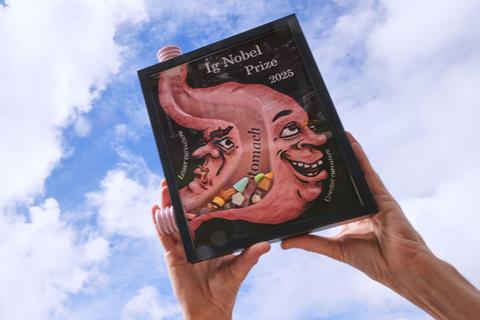

9.07am Ignoble research

Every year, in the run-up to the Nobel prizes, perhaps the second most coveted prizes in science are awarded – the Ig Nobels. These celebrate the science that first makes you laugh, then makes you think, and shows off some of the more unusual research that has been done in the sciences and provides the rationale behind it. Last year, research on tipsy worms won the chemistry prize for revealing how polymers tangle was something Chemistry World reported on back in 2020.

This year, a proposal for a ‘Teflon diet’ won the chemistry prize. The not-entirely-serious concept was that as an inert, tasteless material, Teflon could be used to bulk up food to reduce it caloric content. People on a diet would still get meals that should sate their hunger but with fewer calories.

8.59am The chemistry Nobel prize in numbers

Every year we look at the statistics for the chemistry prize. So far, there have been 116 chemistry prizes awarded since 1901 – the eagle-eyed among you will have noticed that if one prize is awarded every year then that should be 124 prizes in all. However, the prize wasn’t awarded on eight occasions – six of those were due to world wars and another was awarded a year late and on the last occasion the committee considered that no breakthrough of suitable significance had been made. That’s was the case in 1924, which was the year no-one won the Nobel prize in chemistry. Since 1943 there’s been an unbroken run of prize giving, which is set to continue this year.

Of those 116 chemistry prize, 63 have been given to just one person, 25 to two laureates and 28 shared by three laureates. It’s now rare for a single scientist to win the chemistry prize and the last to do so was Dan Shectman in 2011 for his work on quasicrystals – crystals that display short range order, but disorder over longer distances – that he had to fight to get the scientific community to accept. Nobel prizes in the sciences are much more likely to go to multiple people, recognising that scientific discovery is rarely the work of a lone ‘scientific genius’. Many researchers and Nobel-prize watchers feel that these high profile prizes being given to three people at most is one of their greatest weaknesses. Discoveries in the modern era have been about teams of people contributing both lab work and theory, and cannot (or very rarely) be attributed to a single person.

Out of the 195 individuals awarded a chemistry Nobel prize, two have won it twice: Barry Sharpless for asymmetric epoxidation and click chemistry, and Frederick Sanger for sequencing the amino acids in insulin and developing the technology that enabled DNA sequencing. 2008 chemistry laureate Martin Chalfie told us last year that no-one knows how to go about winning a Nobel prize or they’d do it again – these two are clearly the exception here.

The youngest person to ever win a chemistry prize was Frédéric Joliot, who was 35 years old when he won it with his wife Irene Joliot-Curie for their work on radioactive elements. The oldest was John Goodenough, who was 97 years old when he won the prize for work on lithium-ion batteries. Goodenough was still active in research up until his death at 100, a month short of his 101st birthday.

Of the 195 individuals who have won a chemistry Nobel prize, only eight have been women. The last was Carolyn Bertozzi, who won in 2022 for her research on biorthogonal chemistry.

8.48am While we wait for the announcement

If you’re puzzler and have some time to burn before 10.45am BST then our Nobel-themed crossword is for you.

8.38am Keeping it in the family

The academic family tree is ‘building a single, interdisciplinary academic genealogy’ – in other words it’s trying to create a comprehensive list of researchers across many disciplines and who trained them and who they went on to train. It is perhaps unsurprising that many Nobel prize winners have been mentored by academics who have won a Nobel prize – success breeds success. This year, however, the genealogical footprint of the physiology or medicine prize winners is very light indeed with barely any record of them on the ‘tree’. For Mary Brunkow and Fred Ramsdell this may be because they’ve worked in industry rather than academia, but for Shimon Sakaguchi, who works at Osaka University, it’s difficult to say.

For this year’s physics prize we have a better fleshed out understanding of the laureates’ academic ‘ancestry’ than this year’s physiology laureates. John Clarke was mentored by Brian Pippard at the University of Cambridge and, while Pippard was not a laureate he also mentored Brian Josephson, who won the 1973 physics prize for his theoretical work on supercurrents passing through a barrier. This year’s physics prize rewards the discovery of the phenomenon that Josephson made predictions about. Clarke’s ‘grandfathers’ were Pyotr Kapitsa (1978 physics laureate) and Ernest Rutherford (1908 physics laureate). Michel Devoret and John Martinis were, of course, mentored by a future Nobel laureate – John Clarke. This means that one of the grandfathers of these two laureates was the aforementioned Pippard. Two other famous ‘grandfathers’ can be found in their lineages – Wolfgang Pauli (1945 physics laureate) and John von Neumann, who never won a Nobel prize but is still recognised today as one of the greatest mathematicians and physicists to have ever lived.

8.31am Who’s won so far then?

In the run up to the chemistry prize, let’s recap who’s won so far. On Monday, we saw Mary Brunkow, Fred Ramsdell and Shimon Sakaguchi recognised for their discovery of regulatory T cells. This type of T cell oversees the activity of other T cells that fight infection, preventing from going rogue and injuring the body. When there’s problems with regulatory T cells it invariably leads to serious problems such as autoimmune disease, which has made this regulatory control element of great interest to drugmakers with more than 200 trials in this area currently underway.

On Tuesday, John Clarke, Michel Devoret and John Martinis won the physics prize for their work on quantum tunnelling within an electric circuit. They discovered 40 years ago that current could tunnel across a gap in a circuit, something that could be used to develop quantum computers – these machines’ killer app is predicted to be chemistry as they can be used to accurately model molecular systems.

8.23am Welcome to Chemistry World’ s live coverage of the chemistry Nobel prize

Good morning, thanks for joining us for the most eagerly anticipated annual event in the chemistry calendar – the Nobel prize in chemistry. I will be your guide to all the news and events in the run-up to the announcement of the prize at 11.45 CEST/UTC (10.45 BST) at the earliest. We’ll be blooting from @chemistryworld.com and tweeting from @ChemistryWorld and you can find us on Facebook and LinkedIn too and find me at @PatDWalter. If you have anything you think we should share on this live page then get in touch below the line in the comments or @-us on one of our many social media accounts. You can also watch the prize announcement live on the Nobel Foundation site (cameras usually turn on around 11.40 CEST/10.40 BST). If you’re on Twitter then you’ll want to follow the hashtag #chemnobel and #nobelprize for all the latest developments. We hope you’ll stay with us over the next couple of hours in the run-up to the announcement as we’ll be posting some analysis of the Nobel prizes, looking at who’s tipped to win and some Nobel trivia. We’ll also be running a special Nobel-prize themed edition of our regular Re:action newsletter later today, rounding up the best of our stories and the rest of the web. Following the prize announcement, we’ll also be running a webinar on Friday afternoon (1500 BST). We’ll be joined by special guests to talk about the research that won the chemistry prize this year – last year we were lucky enough to have newly minted chemistry laureate and protein design pioneer David Baker join us, perhaps we’ll be lucky enough to joined by another laureate this year. You can sign up for free here.

No comments yet