Visible light shone on the surface of an anthracene-based crystal can cause super-thin layers to cleanly peel off and float away, new research shows.

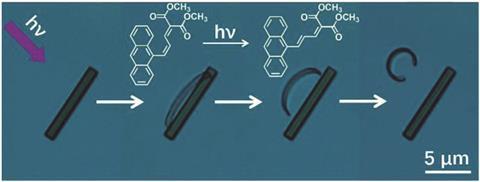

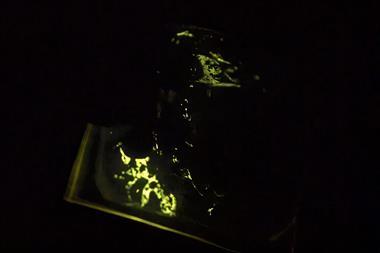

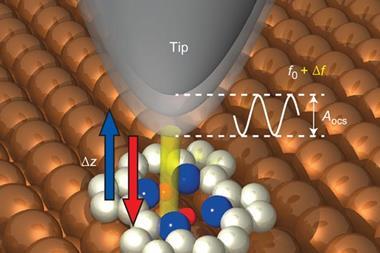

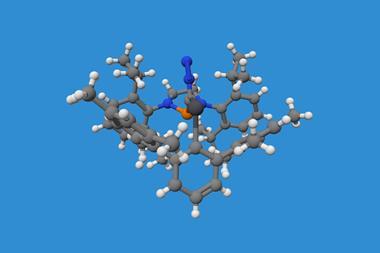

Christopher Bardeen from the University of California, Riverside, US, and his colleagues grew the crystals of cis -dimethyl-2(3-(anthracen-9-yl)allylidene)malonate (DMAAM) from a water solution. They found that increasing the concentration of 1-dodecanol in the solution changed the shape of the crystals from their normal octahedral shape to long, needle-like blocks. To investigate the photochemical properties of these strange elongated crystals, they exposed the surface to a one-second beam of light. To their surprise, a thin layer began to separate from the bulk of the crystal, then quickly peeled away like a banana skin. Bardeen says this is a brand-new type of photomechanical response they call photoinduced delamination.

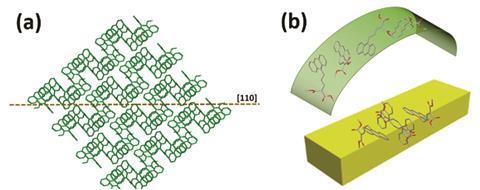

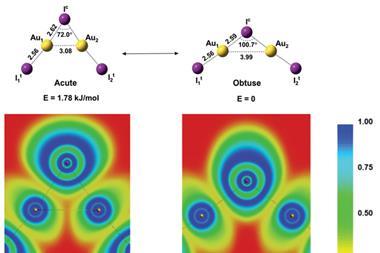

To understand this phenomenon, Bardeen conducted NMR analysis and found that the surface molecules had undergone partial photoinduced cis–trans isomerisation. Bardeen explains that the light causes about 10–20% of the DMAAM molecules, to convert to their trans isomer. This irregular arrangement of molecules cannot efficiently pack together like the rest of the crystal, resulting in an amorphous, non-crystalline layer that is soft enough to deform and peel away.

Thanks to the crystal’s consistent structure, the process can be repeated multiple times on the same block until there is no crystal left. Furthermore, the thickness of the delaminated layer depends on the depth of light penetration, which can be controlled by changing the duration of light exposure.

The researchers say the material could be used to build mechanical switches, renewable surfaces and controllable adhesives.

References

F Tong et al,Chem. Commun., 2019, DOI: 10.1039/c8cc10051a

No comments yet