A biochemist in Mexico may retire if government funding for research dries up

During this difficult time, Chemistry World is checking in with chemists around the globe to see how they are weathering the Covid-19 pandemic.

Lourival Possani, a biochemistry professor in the Institute of Biotechnology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Cuernavaca (UNAM), thinks it’s too soon for the Mexican government to have started easing restrictions aimed at slowing the spread of Covid-19.

The virus officially reached Mexico in February, and there were over 117,100 confirmed cases and about 13,700 related deaths reported in the country as of 6 June. Yet, Mexico began a gradual reopening on 1 June.

‘We should wait longer,’ says Possani, who is one of four academic leaders in a consortium of more than 40 researchers working on projects related to the venom of scorpions, spiders, snakes other animals. Possani’s group, which comprises 10 people, primarily focuses on scorpion venom – isolating and chemically characterising its components, and determining their functions.

UNAM decided on 16 March that its researchers should stay home, and that work in the labs should be reduced to the bare minimum necessary, like caring for research animals, operating important scientific equipment, and maintaining basic administrative functions like paying staff and scholarship funds to graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. In-person courses were also cancelled and went online, and the lab components of these classes are paused indefinitely.

On hold, not closed

‘The regular teaching is done by Internet, the lab work is suspended, the exams and other administrative work will have to wait until the pandemic diminishes,’ Possani says. ‘The only thing that did not stop is writing papers, and exchanging information with the editors and reviewers of journals, and for many students this is an opportunity to write their theses.’

He describes the university as on hold rather than completely closed down, with ‘the minimum activity to keep essential things going on.’ This lockdown was originally supposed to end in mid-April, but it was extended. His university has officially decided that labs will remain under such restrictions until 15 June at the earliest.

Possani, who is an octogenarian, has not been back to his lab since it was closed in mid-March, although a couple of his collaborators are going in to check on things once or twice a week. He has a live population of scorpions there that need to be kept alive with water and crickets. There is also sensitive equipment that requires maintenance, including a protein sequencer. ‘We need to run a sample at least once a week to avoid problems,’ he says. If the machine is not operated for a long period of time, it won’t work properly without mechanical or technical upgrades like substituting valves or changing reagents.

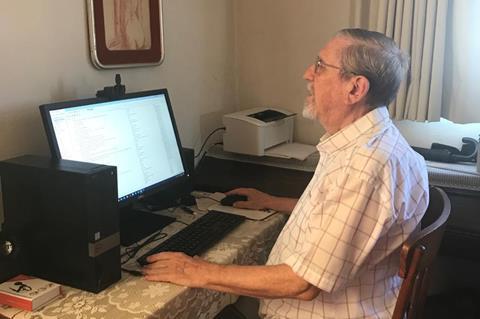

Possani says he’s ‘constantly in contact’ with his team and students by phone and email, and he spends most of his days responding to the many emails he receives from colleagues and students at the university and from abroad.

‘I am dedicated to correcting manuscripts and revising papers submitted to various journals for peer review,’ Possani says. These activities keep him quite busy. On average, he’s been revising about one paper per week, and working hard to finish and submit several publications. Four of them were accepted by journals during this period. ‘All this has been completed now, thanks to the impossibility of going physically to the institute, but allowed me and my collaborators to interchange information and complete the work,’ Possani explains.

Awaiting funding decisions

In addition, he and several colleagues are currently awaiting a final decision from the National Council of Science and Technology of Mexico on funding for a joint grant proposal to work on animal venoms and prepare antivenoms for the country. Specifically for scorpion venom, they are working to develop novel antivenoms made from immunoglobulins originating from humans rather than of horses.

Meanwhile, Possani is sheltering in place at home with his wife in Cuernavaca, which is about 70km north of Mexico City. To maintain normality, they take walks in their garden – usually at least 3km a day – and tend to the grass. They also contact their children and grandsons regularly by phone or internet, watch television and keep up with the news.

Since the lockdown started, their housekeeper has moved in with them. ‘She is now part of our family,’ Possani states. ‘She does not go to her home on weekends.’

Possani says he maybe should have followed in his wife’s footsteps and retired a few years ago, but hasn’t because he’s simply enjoyed his work as a scientist too much. In fact, he believes this is the most academically productive period of his career and would like to continue working as long as possible. In the last decade, he has published about 12 papers per year in international journals.

However, Possani is now seriously considering retirement, and it really depends on grant approvals. ‘If the government stops financing our scientific work, there is no case to keep working,’ he says. ‘It will be better to apply for a retirement.’

Chemists amid coronavirus

How chemists around the world are coping with life and work during the Covid-19 pandemic

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Chemists amid coronavirus: Lourival Possani

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

No comments yet