A biochemist at Johns Hopkins recounts how his lab pivoted to tackle Covid-19 with mini-brains, and how his love of gadgets has helped

During this difficult time, Chemistry World is checking in with notable chemists around the globe to see how they are weathering the coronavirus pandemic.

Johns Hopkins University (JHU) in Maryland, US is still under partial lockdown after stopping non-essential research and ending in-person classes in mid-March due to the pandemic. Prominent toxicologist Thomas Hartung hasn’t been to his office or lab for more than seven months. He is chair of evidence-based toxicology at JHU’s school of public health.

The university reopened its labs in a limited capacity in June, but some key research in Hartung’s group was never really paused. That is because members of his team, which comprises about 20 researchers including his wife, pivoted to address Covid-19.

‘In February or early March, it became clear that our work on mini-brains would be very relevant to Covid-19,’ he recalls. Hartung and colleagues created these so-called ‘mini-brains’ – made up of neurons and other human brain cells that can be used for neurological research – several years ago. The research in question, published in June, suggested the virus that causes Covid-19, SARS-CoV-2, can infect human brain cells.

‘We were considered essential research and were allowed to maintain our lab activities in this area, so we never had to stop and lockdown,’ Hartung explains. This meant that his wife Lena Smirnova, who is running a lot of this Covid-19 related mini-brain research, has continued going into the lab throughout the pandemic.

Strict social distancing

However, Hartung’s metabolomics research did not fare as well. Because the work wasn’t considered essential, the mass spectrometers that support it had to be turned off in early April and were not reactivated until late June. These machines need to build up a vacuum over many days, and it takes about two weeks to get them running smoothly after shutdown, Hartung notes.

JHU has reopened its labs to researchers in phases, with very strict social distancing and hygiene requirements. Researchers can now come into the wet lab and carry out their experimental work, but only in rotations in order to avoid overcrowding. They must also wear personal protective equipment like masks, face-shields, gloves and lab coats, and typically only one person is allowed in the lab per 40 square metres.

The reopening process with its restrictions has been challenging, but Hartung says it was managed extremely well. ‘You can imagine that Johns Hopkins, which is in the news as the centre of wisdom for the novel coronavirus, really doesn’t want to become a cluster of infections,’ he says, referring to the widely-used Covid-19 global tracking map built by experts at JHU’s school of public health.

In-person classes at JHU were cancelled and went virtual back in mid-March and the university’s courses will remain remote until next spring. The only in-person lab courses involve one-on-one teaching for Masters and PhD students.

Hartung is currently teaching two courses at JHU remotely – Toxicology for the 21st Century and Evidence-based Toxicology. Beginning about two years ago, he posts these classes on Coursera, which is an open online teaching platform developed by Stanford University computer science professors in 2012. ‘There are now nearly 10,000 people who are enrolled in our classes, which is incredible for toxicology,’ Hartung notes.

Investing in infrastructure

In addition, Hartung teaches two online classes in bacteriology at JHU, and also gives lectures online at the University of Konstanz in Germany, where he has a joint appointment in pharmacology and toxicology.

Hartung also delivers many individual lectures remotely to universities and institutions across the world, including at the University of Milan in Italy. ‘I don’t have to travel to Milan to give a one-hour lecture,’ Hartung notes. ‘In the past, I very often had to say no to opportunities like this because travel was too difficult, but now I essentially do not refuse any lectures because all I have to do is switch on my computer.’

He communicates with his research team and students virtually, mostly through Zoom for interactive teachings. For recordings, he uses Open Broadcaster Software, a free platform for streaming and recording. It allows him to produce higher quality videos and then edit and export them.

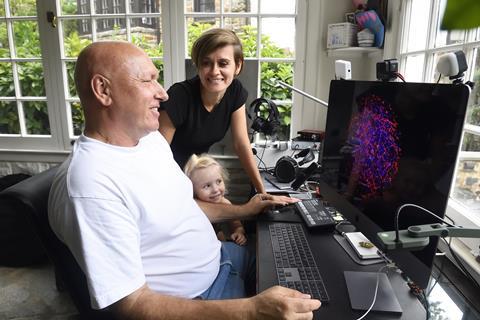

It has been relatively smooth for Hartung to telework because he has invested in high-tech infrastructure that he says is at least as good as his JHU setup. His home office has an advanced computer, a strong Internet connection and professional audio-visual tools, as well as excellent animation and editing programmes.

‘I made these investments before Covid hit, but it was intensified and accelerated by the pandemic,’ Hartung recounts. ‘I am a gadget guy and I like to have the right tools for what I am doing.’

Scientists will not meet ‘so superficially’ anymore

He is thankful to have moved with Smirnova, along with their 13-year-old son and three-year-old daughter, from a small apartment close to campus to a larger house with a garden in September 2019. ‘It was very nice during lockdown for the kids to have the garden and for the four of us to not be packed inside,’ he says. His son is currently doing eighth grade all online, and since late August his daughter has a home teacher for four days a week. That has made home life much more manageable.

When not working, Hartung cooks for his family to maintain his spirits. He took advantage of having a garden for the first time, and planted herbs back in April. ‘The entire summer I explored what fresh herbs mean to cooking,’ he says.

Hartung expects that science, including chemistry, will be ‘profoundly affected’ by the pandemic and its fallout. Scientists will not meet ‘so superficially’ anymore, he says, because in-person meetings and conferences will be reserved for important occasions and will have clearer goals.

Chemists amid coronavirus

How chemists around the world are coping with life and work during the Covid-19 pandemic

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Chemists amid coronavirus: Thomas Hartung

- 40

No comments yet